The decriminalisation of homosexuality

- DateThu, 27 Aug 2015

On 27 August 1975, South Australia became the first Australian state to fully decriminalise homosexual acts.

It’s hard to believe now but up until 1899 in Australia, the death penalty could be applied in cases of buggery or sodomy. For many years thereafter, the maximum penalty was life in prison. Gradually, the penalties were reduced, though in Victoria death remained the maximum penalty until 1949.

Change came slowly and individuals were still being arrested, charged and convicted for homosexual acts during the 1970s.

In 1973, the federal parliament passed a motion supporting decriminalisation but as the power to legislate on the issue was with the states, the 1973 federal motion had no real legislative impact.

In 1994, the federal parliament again legislated but this time it did so to implement Australia’s international treaty obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The Human Rights (Sexual Conduct) Act 1994 had a real consequence in highlighting the incompatibility of Tasmania’s state law on homosexuality with Australian treaty obligations.

Following South Australia’s example, other states (and territories) gradually reformed their laws, though initially not always in a way that gave equal rights to homosexuals: the Australian Capital Territory in 1976, Victoria in 1980, the Northern Territory in 1983, New South Wales in 1984, Western Australia in 1989, Queensland in 1990 and Tasmania in 1997.

Legislation based on equality between hetero- and homosexual acts was passed by the Australian Capital Territory in 1985, Queensland in 1990, Tasmania in 1997, Western Australia in 2002 and New South Wales and the Northern Territory in 2003.

The 1975 South Australian legislation was largely driven by the determination of Don Dunstan who was state premier from 1967 to 1968 and from 1970 to 1979. As Attorney-General in the state Labor government from 1965 to 1968, he had drafted a reform bill but wanted to wait until public opinion was more sympathetic.

The 1972 murder by drowning in Adelaide’s Torrens River of a homosexual academic, Dr George Duncan, raised public awareness of widespread harassment of homosexuals and resulted in a push for law reform by some parliamentarians and by the gay rights organisation known as the Campaign Against Moral Persecution (CAMP).

Gay rights organisations were established during the late 1960s and early 1970s in Australia: a period of wider radical social change. The ACT Homosexual Law Reform Society was formed in 1969 and the Daughters of Bilitis in Melbourne in 1970. Sydney-based CAMP galvanised the movement and branches were soon set up in Australia’s other capital cities and on university campuses.

South Australia’s first attempt at reform was led by Murray Hill, a Liberal Country League member of the Legislative Council. Under the Criminal Law Consolidation Act Amendment Act 1972 homosexual conduct remained illegal but the Act allowed for a defence in cases where the conduct had occurred in private among men over the age of 21.

The 1972 reform was a long way from the 1975 decriminalisation which, through the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Amendment Act 1975, abolished offences of buggery, gross indecency and soliciting, and also created an equal age of consent for homo- and hetero- sexual acts.

Today, there may be debates about same-sex marriage but no-one advocates the re-criminalisation of homosexuality. It is interesting to look around the world, though, at the places where homosexuality is still a crime. Invariably, they are countries lacking in democracy.

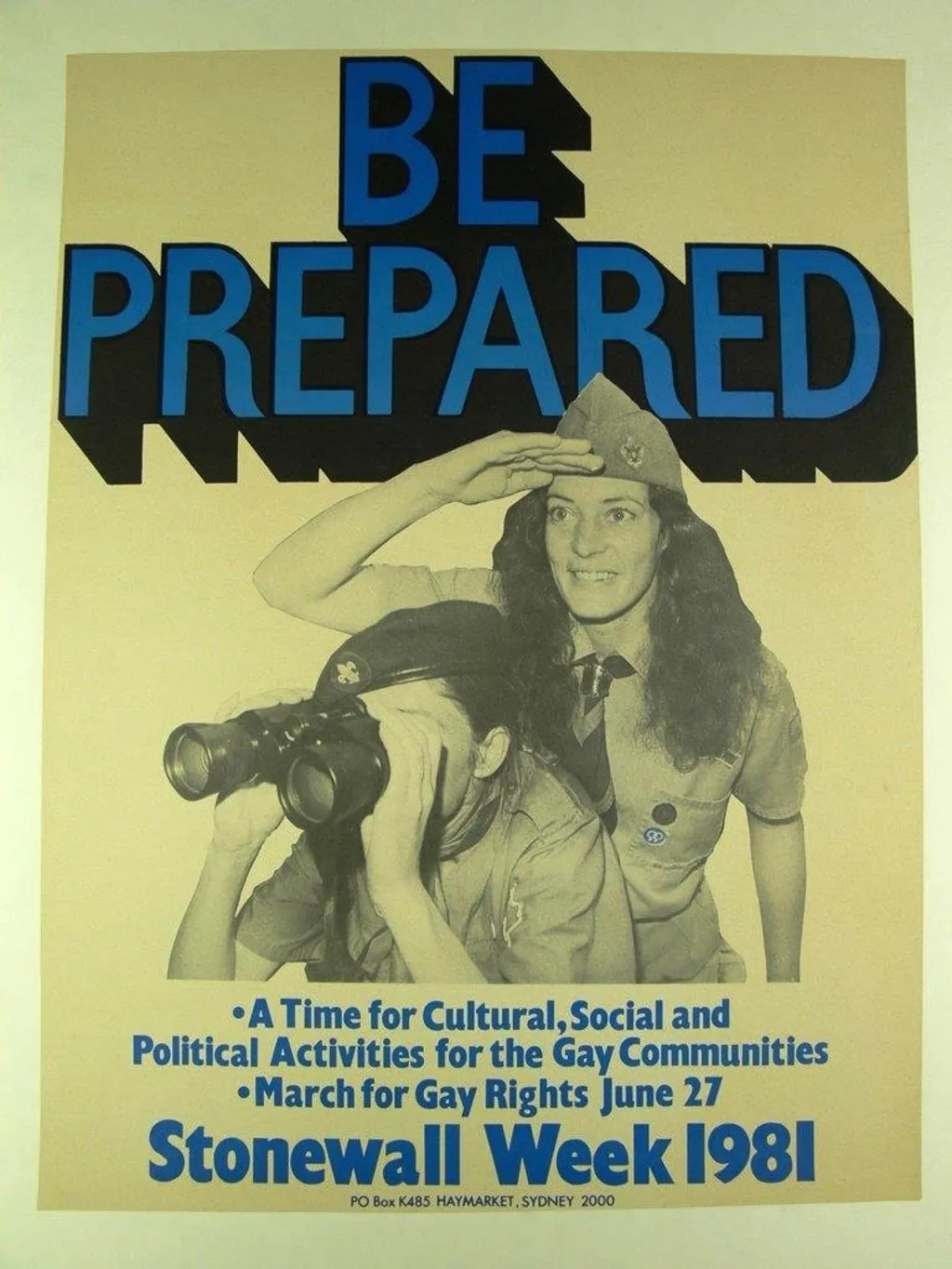

Poster for 1981 Stonewall Week. Credit: MoAD Collection.