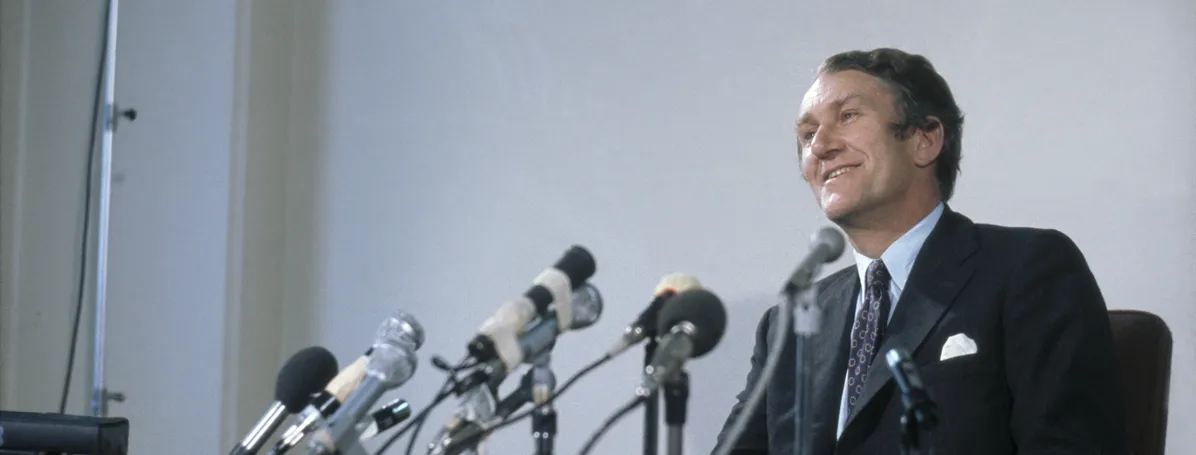

Reflections on Malcolm Fraser

- DateMon, 23 Mar 2015

In his later years Malcolm Fraser was generally seen as the politician who moved most spectacularly from the right to the left of the political spectrum.

The man denounced by the left for his role in the dismissal of the Whitlam Government by the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, in November 1975 became in his later years the left’s hero, as he denounced Liberal and even Labor governments, especially on refugee policy and the American alliance. His last book, Dangerous Allies, urged Australia to end the alliance and its longstanding approach of ‘strategic dependence’ on powerful allies. How does this square with Fraser’s role as Minister for the Army and then Minister for Defence during the Vietnam War, a commitment of which he was one of the coalition government’s most articulate defenders?

A close look at his actions in the 1960s and 1970s reveals some early signs of his later attitude to the American alliance. After ten years on the backbench, his first ministerial appointment, as Minister for the Army, came when Harold Holt formed his first government in early 1966. As Minister for the Army, Fraser made several visits to Vietnam and engaged with the issues the Australian Army faced there, including the pronounced difference in the tactics employed by the Australian and American armies. Fraser, like many of the Army’s leaders, wanted the Australians to focus their operations on one province, where they could use the counter-insurgency tactics that they had used skilfully, successfully and with minimal casualties in conflicts in Malaya and Borneo. He was concerned by the American reliance on advanced technology and heavy firepower, their willingness to accept high casualty rates, and their desire to use the Australians in combined operations over a wide area.

Fraser was appointed Minister for Defence by Prime Minister John Gorton after the 1969 election. The service ministers, the armed services and his department now found themselves driven by an extremely active and assertive Minister with the power of a senior Cabinet portfolio. But his energy and vigour were not directed only towards Australians. Fraser long remained proud of his handling of the contractual arrangements with the Americans for the acquisition of the F-111 aircraft. Cost blow-outs and delays in production were embarrassing the Government. Fraser’s vigorous and confrontational tactics on a visit to Washington were based on technical advice that established weaknesses in the information provided by the Americans. While his critics continued to portray him as an unrepentant hawk, Fraser in fact pushed the Americans hard. There was no suggestion at this time of a complete break from the alliance in pursuit of ‘strategic independence’. In the circumstances of the day, that would have been inconceivable: but Fraser was already indicating that he would not genuflect obsequiously before great and powerful friends.

Fraser appointed a formidable and experienced public servant, Sir Arthur Tange, as Secretary of the Department of Defence, saying that he needed someone in that position who could stand up to him. The two men predictably clashed, before reconciling to form a close partnership. Fraser often described Tange as the public servant he most admired, and many of the policies and reforms associated with Tange originated in Fraser’s term as Minister for Defence. They included not only the merging of three services into one Australian Defence Force and the uniting of five departments into a single Department of Defence, but also a new strategic approach that placed less emphasis on the American alliance and more on the defence of the Australian continent and its environs. The major elements of the ‘defence of Australia’ strategic approach were given formal expression in Australia’s first Defence White Paper, brought down in Fraser’s first year as Prime Minister.

The reshaping of strategic policy is only one example of the ways in which Fraser, as Prime Minister, quietly consolidated and institutionalised many of the changes in national security policy and structures that were initiated, often with considerable flourish and fanfare, by the Whitlam Government. The reorganisation of the Australian Defence Force and the Defence Department was another. There was no suggestion of reversing the recognition of China. Instead, Fraser ensured that the development of a strong relationship with China, and with as many of our Asian neighbours as possible, would become a bi-partisan policy.

Fraser’s sympathy for non-white peoples, especially Britain’s colonial subjects in Asia and Africa, was sparked by his personal experience as an undergraduate at Oxford. It was a consistent and prominent element in his foreign policies as Prime Minister. While there was much continuity in his Asian policies, Fraser gave an unusual degree of attention to African issues, notably in his opposition to South African apartheid and his support for the independence of Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia).

Fraser implemented the reforms of Australia’s security and intelligence agencies recommended by the Royal Commissioner appointed by Whitlam, Justice Robert Hope. Fraser also appointed Hope to another review of security arrangements, following an apparent terrorist incident at Sydney’s Hilton Hotel. Fraser’s successor, Bob Hawke, appointed Hope to another Royal Commission, ensuring that between the mid 1970s and mid 1980s three successive Prime Ministers shared responsibility for the most far-reaching reform of the Australian intelligence community.

In many areas of national security, Fraser’s term as Prime Minister consolidated and extended the reforms of the Whitlam period. It was not altogether surprising that, in their later years, the two men became close, notwithstanding the extraordinary tensions associated with the Dismissal.