Only human – disability in Australian politics (part 2: human rights and human laws)

- DateSat, 03 Dec 2016

If you look in the right places, disability has not only been with our leaders since the beginning but in our political debates.

In my first blog on disability in Australian politics we looked at the rarely discussed disabled lives of our nation’s leaders since 1901.

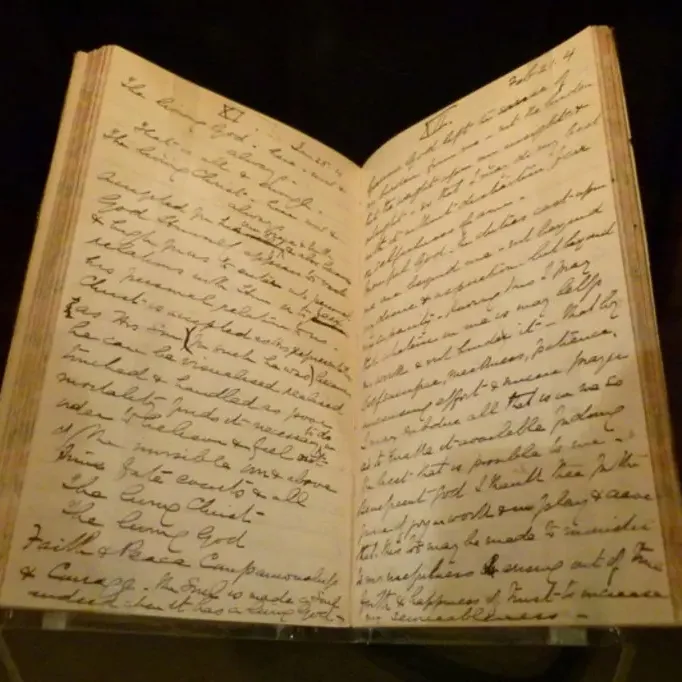

Indeed you can find progress in the crafting of our founding document. Unlike the draft of the Australian Constitution presented in 1891, the version which got over the line in 1900 included a clause (clause 51 (xxiii)) empowering the Commonwealth Parliament to introduce invalid and old age pensions.

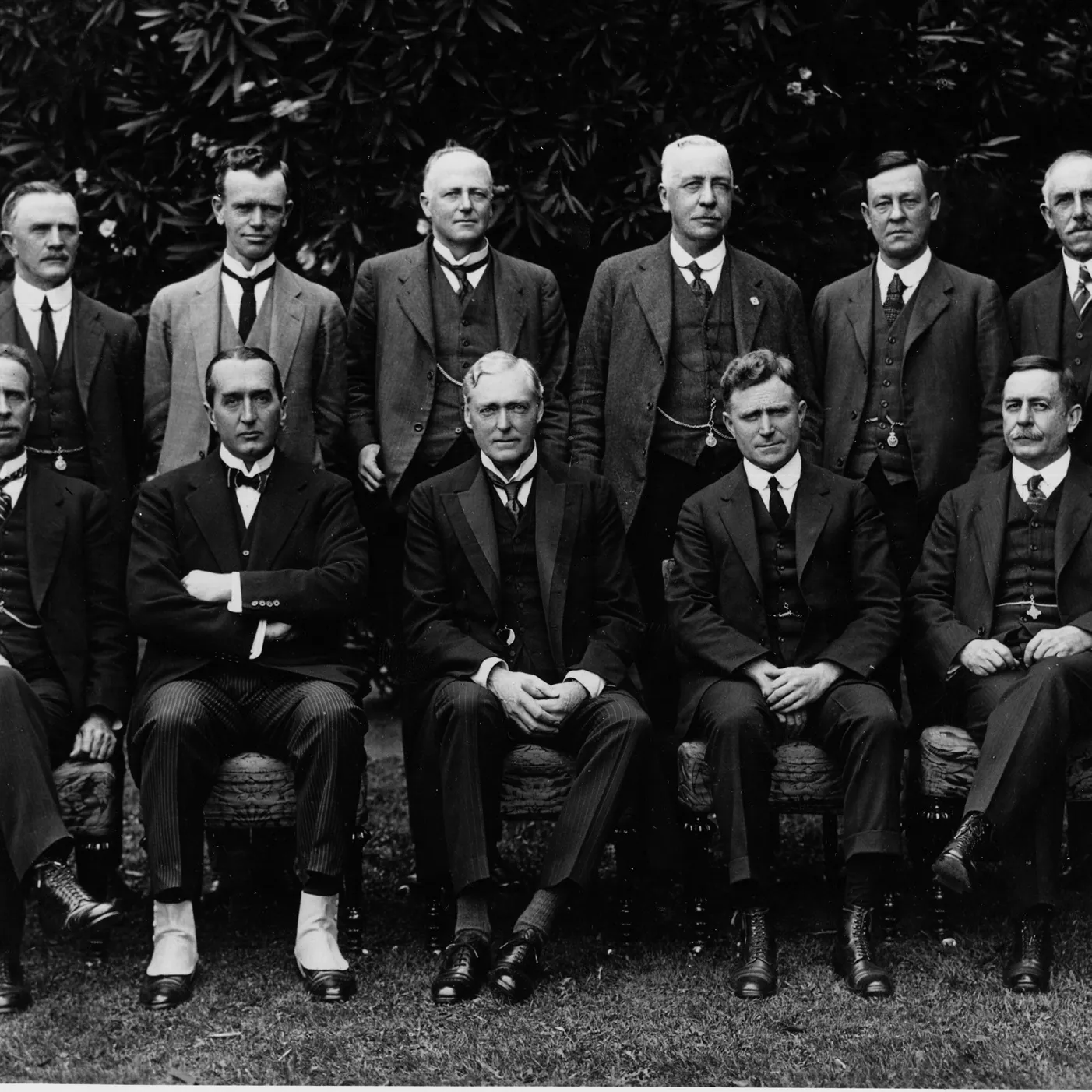

The Labor Government of Andrew Fisher began to pay means-tested invalid pensions in October 1910.

The major test for disability policy would be the First World War and evidence that survives suggests the authorities of the time were unprepared for the scale of rehabilitation and disability support services that would be required.

According to Janet Lynch, the government had optimistically planned for the short-term rehabilitation of injured soldiers, and initially focussed its resources on the ‘most severely disabled’ and those who were displaying physical signs of illness at war’s end.

Repatriation Minister Senator Millen delivered a speech to the Australian Senate in 1918, in which he described ‘totally and permanently incapacitated’ soldiers as ‘those who are bed-ridden and those who are paralysed, and who will always require nursing and medical attention’. However, the government had not foreseen that the demand for hospitalisation of psychosocial disability among veterans would escalate, in an era when post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was poorly understood.

The task of rehabilitation seems to have fallen mainly on the Red Cross and, more darkly, on ‘insane asylums’. It is telling that a thrust of advocacy by veterans and families following the Great War was to keep soldiers in military hospitals and out of State Government and charitable run asylums. Nearly a century later people are still telling their stories of abuse, neglect and violence in disability institutions through a Senate Inquiry.

It appears that lessons were learned in a more coordinated response as the end of the Second World War approached.

In July 1944 the Standing Committee on Re-employment and Re-establishment set up a sub-committee on the rehabilitation of disabled members of the forces. It recommended a comprehensive scheme for the re-establishment of disabled men and women, with the Department of Post War Reconstruction providing a coordinating authority.

In January 1945 Ben Chifley proposed to the War Cabinet that the Department of Social Services should immediately set up an interim scheme for the care and re-establishment of disabled ex-servicemen who were not eligible for the benefits of the Repatriation Act. They would receive a rehabilitation allowance of 50 shillings per week.

By 1947 the Department of Social Services had opened rehabilitation centres in all the capital cities except Hobart and more than 7,000 returned servicemen had received treatment and assistance.

In February 1948 Chifley announced that a new rehabilitation scheme would be established, providing medical treatment and vocational training for disabled ex-members of the services, invalid pensioners and those claiming or receiving unemployment or sickness benefits. Subsequently, legislation was passed establishing the Commonwealth Rehabilitation Service.

Brian Howe notes, with some justification, that there was little action outside the wars although Sir Robert Menzies writes in his memoirs that his was the first Government to get the Commonwealth involved in funding of mental health and improving some of the standards in State run institutions.

From its first budget, the Whitlam Government raised invalid pensions. The Whitlam Government also enacted reforms to create four new social security benefits. These included the Handicapped Children’s Allowance to guardians of severely disabled children.

The Whitlam Government also passed the Handicapped Persons’ Assistance Act which provided increased funding for volunteer organisations providing support services and employment to people with developmental disabilities, and increased subsidies for some of their staff. The Government favoured this model of support because, as Social Security Minister Bill Hayden argued, ‘voluntary organisations have an individual touch. They can deal with the person as a whole.’

Soon after coming to government Whitlam commissioned an inquiry headed by New Zealand judge Owen Woodhouse into a national accident compensation and rehabilitation scheme. Its report recommended a system of no-fault compensation for all injuries – extending beyond the present coverage of workers’ compensation and motor accidents to cover anyone with an injury, whether acquired or from birth, and those with incapacity due to illness.

Legislation for a scheme covering acquired injuries, financed through payroll tax and excise duties, was before parliament when the Whitlam government was dismissed in 1975. It had aroused opposition from insurance companies and lawyers, and was abandoned by the incoming Fraser government.

While the NDIS would not see the light of day until 40 years later, the Fraser Government did make a push towards attitudinal change. In 1976 the United Nations declared an International Year of Disabled Persons to be held in 1981 and the Fraser Government responded with a national secretariat, including staff with disabilities, a full free to air advertising campaign – ground breaking for its time and designed by Phillip Adams – called Breaking Down the Barriers and a number of programs covering aids and equipment for people with disability. The Governor General Zelman Cowan was the patron of the year. There was an emphasis on local IYDP committees and the voice of disabled people being heard for the first time. In the 1980s disability began to be widely seen as about international human rights, as well as human welfare, in Australia.

This fascinating video from the National Film and Sound Archive talks about a street march and celebration for people with disabilities and provides some insights into the hopes (and disappointments) held for the year.

The election of the Hawke government in 1983 saw significant reforms. One example was the Handicapped Programs Review, New Directions 1985, which recognised ‘the need for a change of culture in disability policy towards people’s abilities to make a contribution to society’. This approach worked through the Disability Services Act (1986), which emphasised that ‘people with disabilities should have the same rights as other members of Australian society to realise their individual capacities for physical, social emotional and intellectual development.’ There began to be Service Standards with expectations that funded services would treat people better and recognise their rights.

People with disabilities came to Parliament House in 1985 to successfully speak out against a consumption tax. Government policy also identified strongly with the international decade of the disabled through the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) passed in 1992. This was followed by a Commonwealth Disability Strategy launch in December 1994 which was meant to ensure compliance by Commonwealth Departments with the Act. Results have been uneven, especially in employment, but the Act has made some breakthroughs on education and disability access in new buildings.

The Howard Government initiated a number of programs including funding for Mental Health and early intervention for Autism. Australia also took a further step on human rights and signed the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disability towards the end of Howard’s term in 2007.

The incoming Rudd government in 2007 placed an ambitious Bill Shorten in charge of disability. The government had committed to develop a National Disability Strategy within COAG with the States and Territories. The drive to develop a National Disability Insurance Scheme quickly became a key part of the strategy.

In 2010, the Australian Government asked the Productivity Commission to recommend options for a national disability scheme that would ‘enhance the quality of life and increase economic and social participation for people with disability and their carers.’

The inquiry attracted more than 1,000 public submissions from the disability sector and from people with disability. Introducing a law to provide disability insurance to Parliament in 2013 the then Prime Minister Julia Gillard said that the reform would endure:

‘Today we give an assurance to all Australians who live with disability and to those who care for them. DisabilityCare Australia will be here when you need it … election after election, decade after decade, generation after generation.’

In that speech Gillard mentioned a photo taken of her by Sophie Deane, a 12 year old girl with Downs Syndrome who she met while signing the NDIS agreement with Premier Napthine. It became her favourite photo and today features on her Twitter account as well as on the cover of books on her days as Prime Minister, such as Gravity by Mary Delahunty.

With an agreement between Australian and state governments in reach, and the passing of the NDIS Act 2013, trial sites were chosen around the country, operating from July 2013.

The Abbott and Turnbull Governments committed to the ongoing rollout of the NDIS. Malcolm Turnbull made the signing of an NDIS agreement one of the first official duties of his Prime Ministership and in November 2016 recommitted to the National Disability Strategy under the guidance of a new National Disability and Carers Advisory Council.

The Museum of Australian Democracy is itself an example of progress with the Disability Reference Group making a critical contribution to the direction of the Disability Inclusion Action Plan. I hope next time you visit the museum you look at the story of our politics in a new light – one where disability is no longer at the margins of Australia’s history.