The Introduction of Decimal Currency: How We Avoided Nostrils and Learned to Love the Bill

- DateSun, 14 Feb 2016

On 14 February 1966, one of the most fundamental aspects of Australians’ lives underwent a radical transition.

It was the day we changed from an imperial system of currency to decimal currency. Every balance in every bank account; every wage in every pay packet; and every price on every item in every place money was ever transacted—from milk bars to stock markets—was converted from pounds, shillings and pence to dollars and cents. People had to swap their quids, bobs, zacs and trays with new notes and coins in new colours, shapes, sizes, weights, names and values. Few public policies come bigger than this.

A decimal system divides amounts into lots of ten, making numbers easier to calculate. Policy change is much more difficult. Australians had been thinking about the decimal system since 1901, when a Decimal Currency Select Committee started considering a currency based on a sovereign consisting of 10 florins. But this would have put us out of sync with our then major trading partner, Great Britain, from whom we inherited the imperial system. So we were stuck with 12 pence to a shilling, 2 shillings to a florin, 5 shillings to a crown and 20 shillings to a pound.

But the idea gathered momentum. Many soldiers returned from the First and Second World Wars familiar with decimal currency. In 1959 the federal government appointed another committee to investigate the issue. After it became apparent that public opinion largely supported decimal currency—and that most other industrialised nations were already using it—the government finally stopped following Britain’s lead. In April 1963 it announced that our currency would be based on a 10 shilling/100 cent system. Australians were invited to suggest a name for the new currency unit.

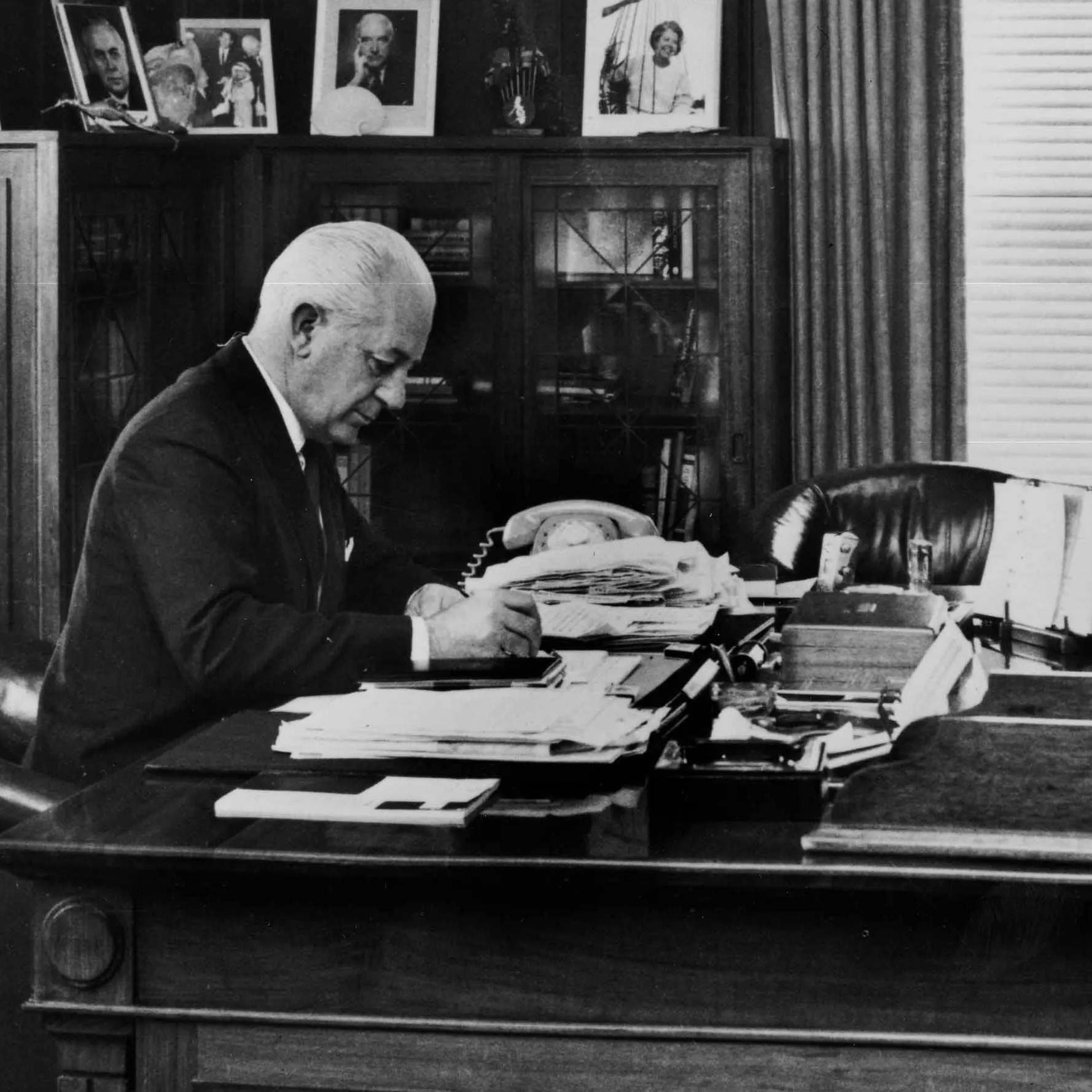

More than 1,000 official suggestions were compiled. Some people thought the ‘Austral’ had a nice ring to it. The ‘Deci-mate’ never really stood a chance, but the ‘Kwid’, ‘Digger’, ‘Dinkum’, ‘Kanga’, ‘Boomer’, ‘Roo’ and ‘Oz’ were popular. The ‘Emu’ also enjoyed some support, and some people even liked the ‘Ming’ – the nickname of the then Prime Minister, Sir Robert Menzies.

Finally, on 5 June 1963, the winner was announced. The nation held its breath as Treasurer Harold Holt announced, with great confidence and certainty, that our new currency would be called … the ‘Royal’. It was a dignified, distinctive name, Holt said, and emphasised Australia’s link with the Crown. It also had a pleasing brevity and, unlike the other suggestions, would be fully acceptable to the public.

It wasn’t. Three months of public outrage followed. Letters to the Editor and newspaper columns were filled with words like ‘insulting’, ‘disastrous’ and ‘laughable’. Some people blamed the ‘Royal’ on the sentimental Menzies, who had been elevated to the Most Noble Order of the Thistle by Her Majesty herself in March 1963. Labor leader Arthur Calwell was reported as saying the ‘Royal’ was a product of ‘antiquated thinking’. Zara Holt received death threats. A vast majority of the Australian people did not want ‘Royals’ in their pockets.

Cartoonist John Frith presents his thoughts on the Royal.

So the government reconsidered the ‘Austral’. However, Holt is said to have remarked that the Australian accent would make any amount of Australs in the teens—for example, ‘14 Australs’—sound like ‘40 nostrils’. It seemed likely that people wouldn’t want Nostrils in their pockets, either. In September Holt announced to a generally relieved Australia that the currency would be called the ‘Dollar’. An unoriginal and perhaps dreary name, the Dollar at least made sense. The pound would convert to 2 dollars, the crown to 50 cents, the florin to 20 cents and the shilling, 10 cents. The sixpence was consigned to Grandma’s Christmas pudding and the halfpenny was history.

An education campaign swept the nation to explain how it all worked. The airwaves were awash with TV and radio advertisements guaranteed to stir the cockles and engrave the minds of all patriotic Australians: the character Dollar Bill singing a jingle (written by Ted Roberts) to the tune of the folksong Click Go the Shears:

In come the dollars and in come the cents

To replace the pounds and the shillings and the pence.

Be prepared folks when the coins begin to mix

On the 14th of February 1966.

Clink go the cents folks

Clink, clink, clink.

Changeover day is closer than you think.

Learn the value of the coins and the way that they appear

And things will be much smoother when the decimal point is here.

(Repeat chorus)

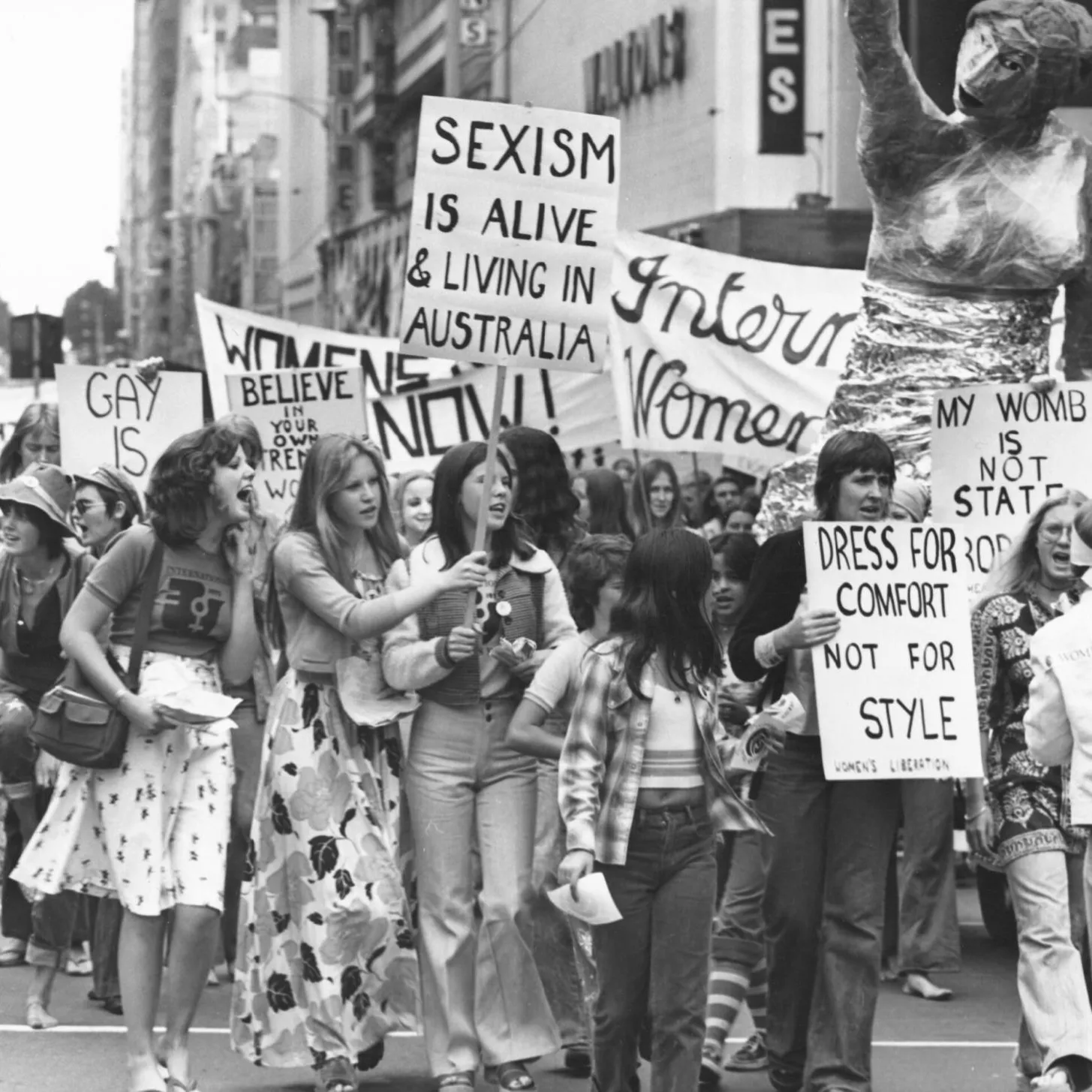

The years of careful planning and education paid off. When 14 February dawned at last, Australians took it (and the fiddly two-currency transition period) in their stride. Stuart Devlin’s designs for the menagerie depicted on the reverse side of the coins reflected the nation’s growing pride in its unique identity. Although Queen Elizabeth II remained on the coins’ obverse side, the new currency marked for some people a symbolic and practical loosening of Australia’s cultural and political ties with Britain. Things seemed much more modern now.

The 50 cent coin was controversial, however. Its circular shape meant it was easily confused with the 20 cent piece, especially by people with a vision impairment. And when in 1967 the price of silver rose above the face value of the coin, which was composed of 80% silver and 20% copper, the Royal Australian Mint suspended production. In 1969 production began on a revised 50 cent coin in its now standard dodecagon shape, with its copper-nickel composition making it about 2 grams heavier than the original.

The Museum’s collection features this set of mint 1966 coins, complete with the round 50 cent piece, in a leather pouch embossed with gold initials ‘H.E.H.’. The set was presented to Harold Edward Holt for his role while Treasurer (1958–1966) in fostering the decimal system into being. Holt tragically disappeared not long after, but his legacy runs through the daily lives and wallets of all Australians.