A doctor in the house? Five doctors who served in the Commonwealth Parliament

- DateMon, 26 Nov 2018

In 2018, Dr Kerryn Phelps was officially sworn in as the Member for Wentworth in the House of Representatives.

Dr Phelps became a household name due to her tenure as head of the Australian Medical Association, the professional body representing doctors and health practitioners. However, Dr Phelps is far from the first medical doctor to transition from practice to parliament...

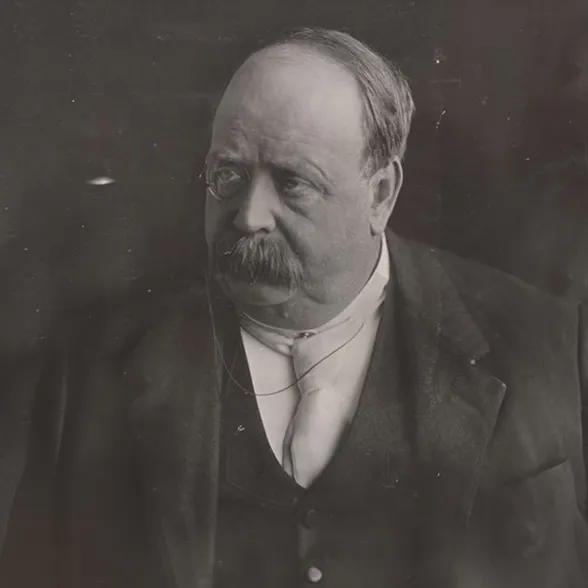

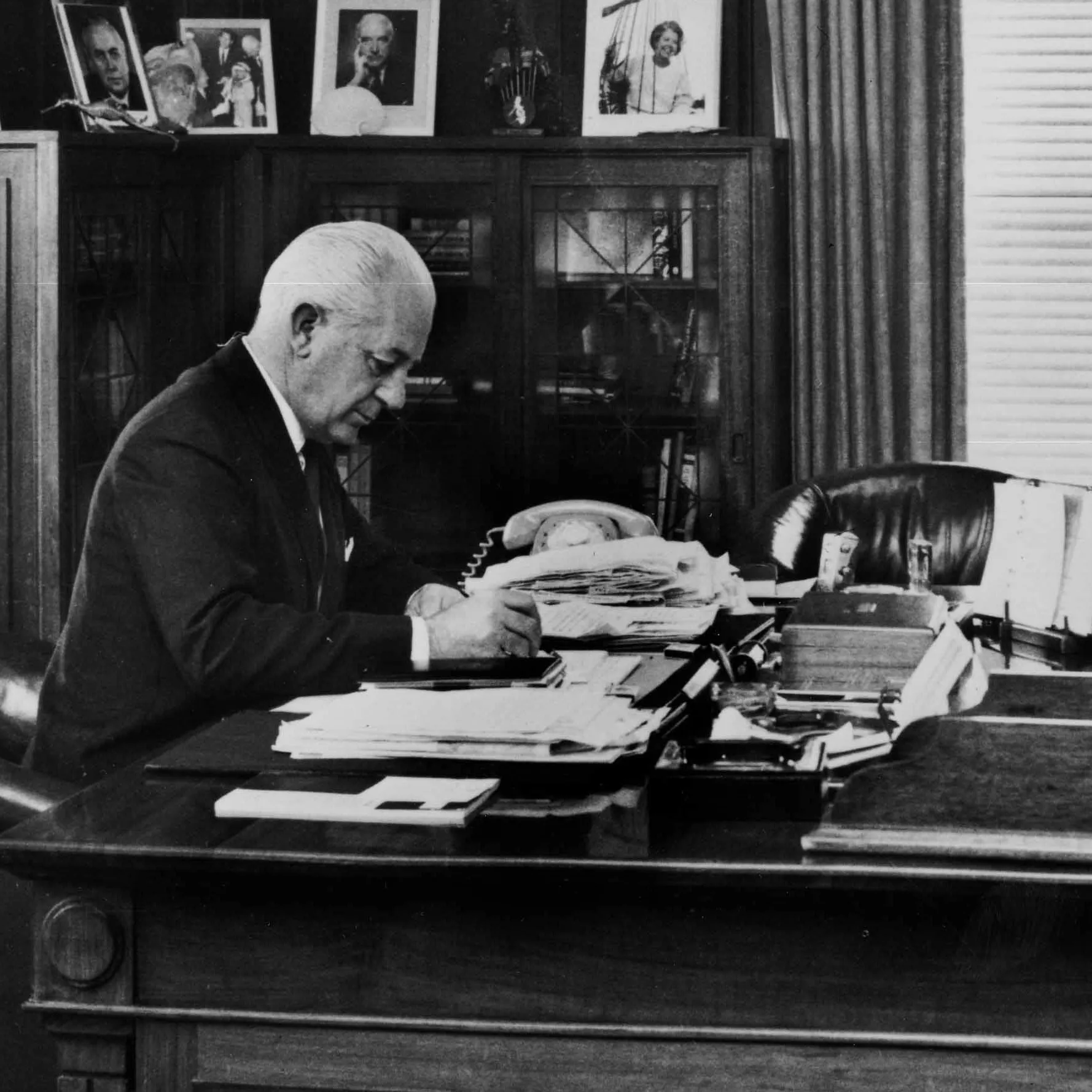

Dr Earle Page, later prime minister and a long-serving member of parliament, began his professional life as a doctor. In 1916, aged 35, Page enlisted in the Australian Army Medical Corps and was posted to, among others, a troop ship, a military hospital in Cairo and a hospital in England. But his most dangerous role was as a surgeon at a casualty clearing station near the French battlefront. Located just beyond the range of artillery fire, these stations were where battlefield casualties were taken and stabilised before being moved to a military or field hospital. Conditions were harsh and the work harrowing: Page and his team managed up to 900 casualties a day, with some doctors working for more than 72 hours straight. Page only served there a few months before receiving his discharge papers. As one of the few medical doctors in parliament when it relocated to Canberra, Page was often called upon to help his fellow MPs - on one occasion in 1928, when there was no other surgeon available, Page performed an emergency appendectomy on a Labor member, Parker Moloney. He was always known to his colleagues as 'Doc' and never lost touch with his roots as a country doctor.

Earle Page (in the suit) as a surgeon in a field hospital in 1916. Page’s military service was difficult and dangerous, and he was always remembered fondly for putting his life on the line. MoAD Collection

Dr Felix Dittmer, Senator for Queensland from 1959 to 1971, once provided a measure of ‘help’ to a colleague. Dittmer’s fellow Labor Senator Harry Cant was quite drunk while a vote was taking place in the chamber. He was desperate to throw up and did so in the only place available - one of the desk drawers.

This was not a good look for Cant. Fortunately, Dittmer attended to Cant as he looked for a place to recover and was taken to Royal Canberra Hospital for treatment. According to veteran Press Gallery journalist Rob Chalmers, Dittmer diagnosed Cant with ‘renal colic’, and denied firmly to the press that drunkenness was involved. The story made the papers but Cant’s condition was barely mentioned, with the ‘renal colic’ cover story seemingly working. From that point, according to Chalmers, anyone who turned up looking the worse for drink in the chamber was met with cries of ‘renal colic!’ from their fellow senators.

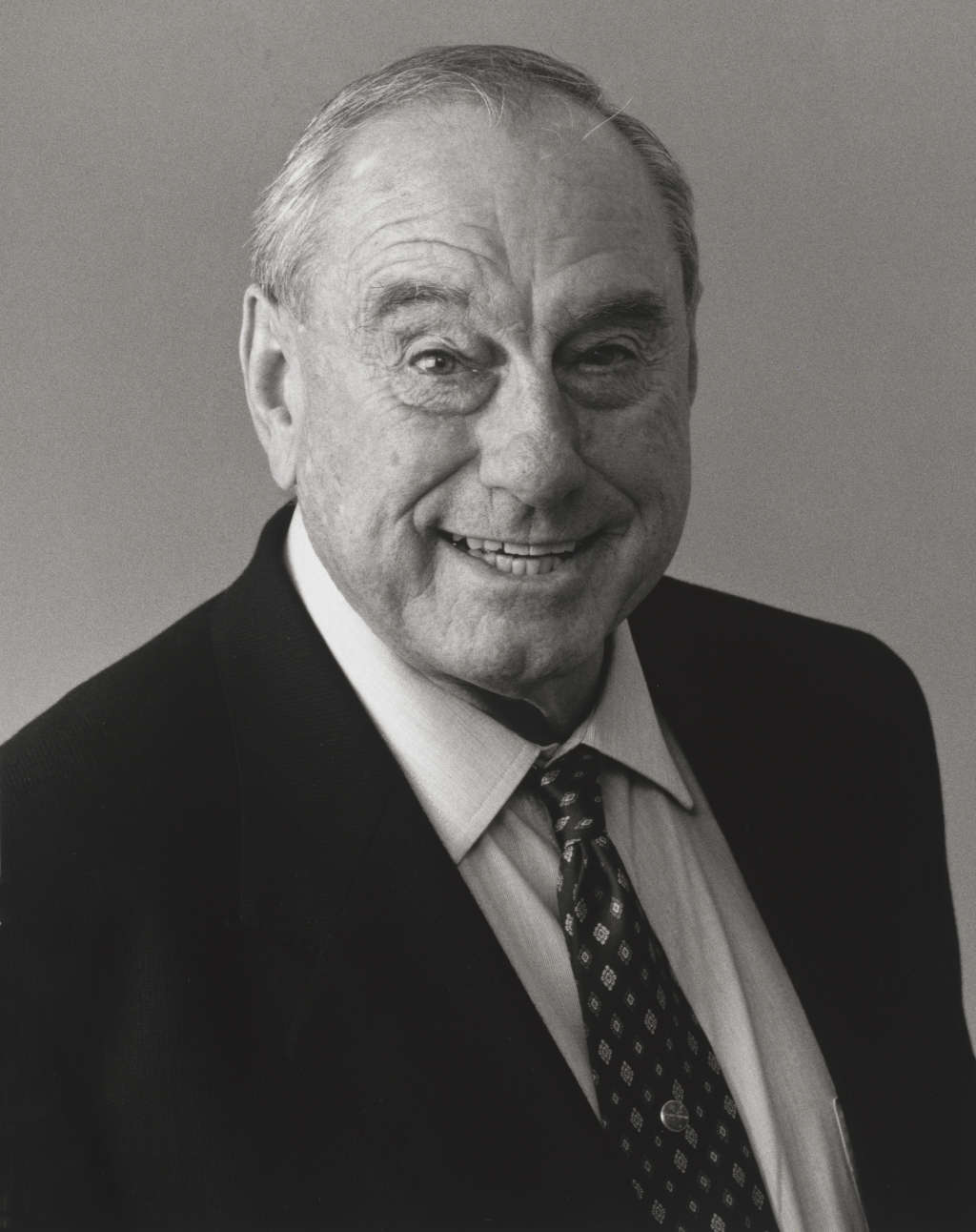

Dr Glen Sheil was known by his colleagues as a good doctor. Having been a medical practitioner in Queensland before his Senate career, Sheil took a strong interest in health policy, and vehemently opposed the Whitlam government’s health insurance scheme, which would eventually evolve into what we now know as Medicare. Sheil once told the chamber 'Health is the single most important item on anybody's agenda. A government—any government—must think twice before interfering with it.' Sheil would later find fame, or infamy, as the shortest-serving minister in history - his appointment as Veterans Affairs minister was terminated (technically it never even started) after two days in 1977 after he made comments supporting apartheid in South Africa. Despite his controversial political career, Sheil remained a doctor through and through - one biographer records that he once saved the life of Senate colleague Margaret Guilfoyle after she nearly choked on a fishbone in the Parliamentary Dining Room.

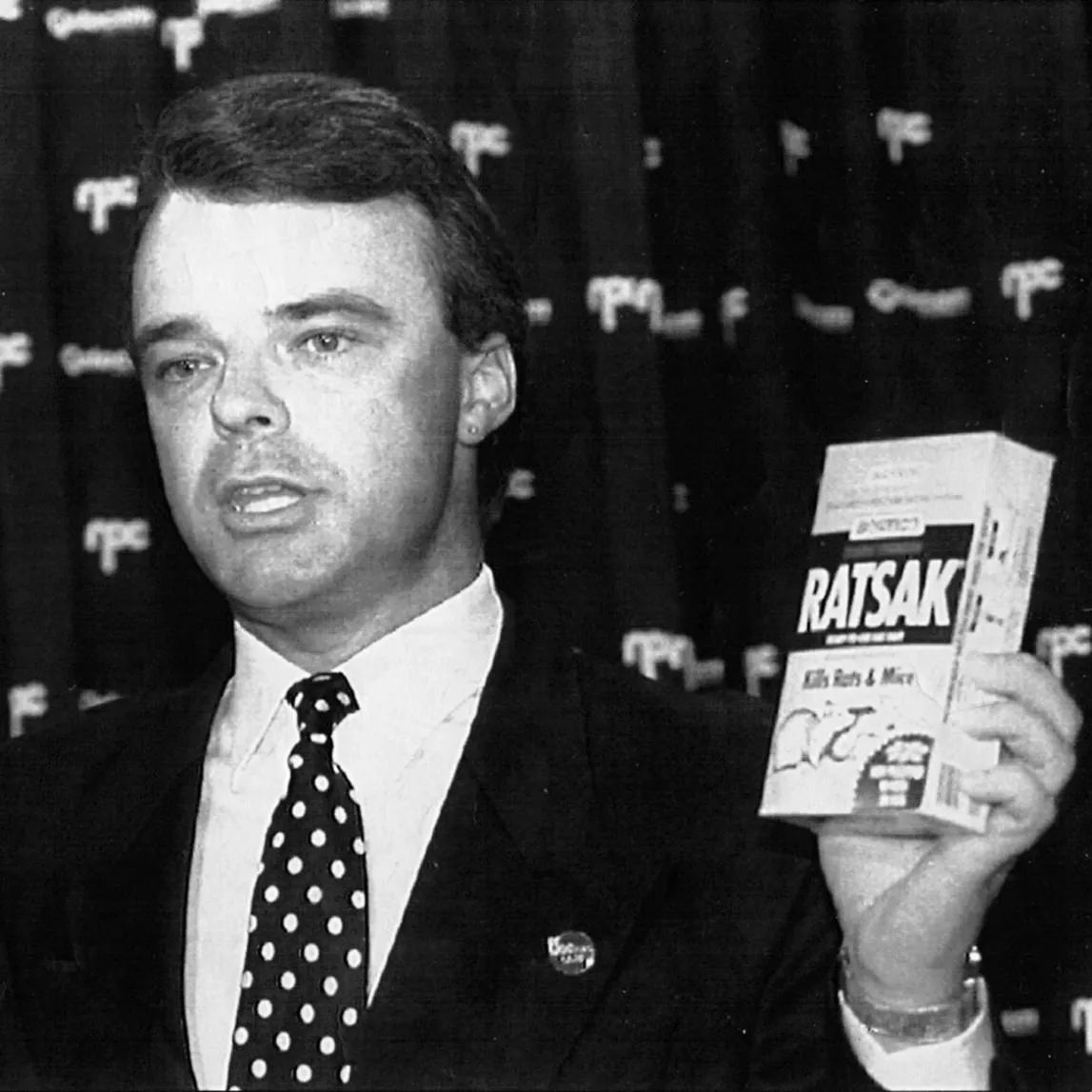

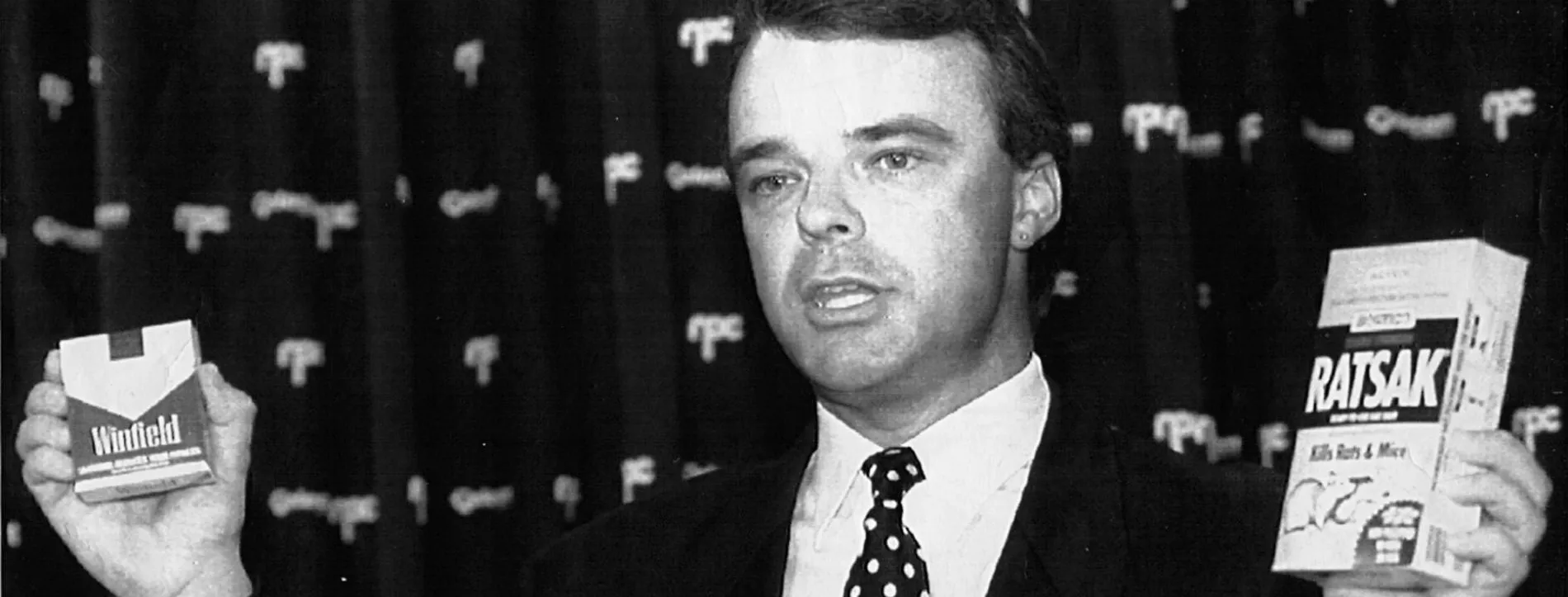

Dr Brendan Nelson was the youngest-ever federal president of the Australian Medical Association, elected in 1993 at the age of 34. Nelson’s youth and policy agenda made him a national figure. He pledged to improve relations with the federal Labor government, and called for a new focus on environmentalism, unemployment and Indigenous health. He was also a very strong campaigner against smoking. Having once been a member of the Labor party, in 1995, Nelson surprised many by seeking, and winning, Liberal preselection for the blue-ribbon seat of Bradfield, in Sydney’s northern suburbs. In 2001 he became federal Minister for Education and in 2006 Minister for Defence. Nelson was elected leader of the federal Liberal Party in 2007 following the Howard government’s defeat, before losing the leadership to Malcolm Turnbull nine months later. Nelson was Leader of the Opposition during Kevin Rudd’s Apology to the Stolen Generations, which he supported. He resigned from parliament in 2009 and served as Ambassador to the EU and Representative to NATO, before taking up an appointment as Director of the Australian War Memorial in 2012.

Dr Bob Brown's career in medicine was notable for its brush with both politics and celebrity. While practising at Royal Canberra Hospital in the late 1960s, Dr Brown refused to certify young men who had been conscripted as medically fit to fight, ensuring they avoided combat duty in Vietnam. There’s more than one way for a doctor to save lives!

In 1970, Brown went to work in the United Kingdom, and for a time was a resident at St Mary Abbot's Hospital in Kensington, London. One night, Brown was the doctor on duty when a patient was brought in, a young American who had choked on his own vomit after taking barbiturates. That person was guitarist Jimi Hendrix. Some media reports years later reported that Brown was the doctor who certified Hendrix dead, which wasn’t true, but nevertheless it was a notable, if morbid, brush with fame. Years later Brown would reflect that at the time, he thought he and Hendrix had little in common, but he came to see they shared political ideals, a passion for peace and disarmament, and a faith in humanity.

Dr Glen Sheil’s politics was deeply influenced by his career as a doctor, but he was not always rewarded for his outspoken views. Courtesy National Library of Australia

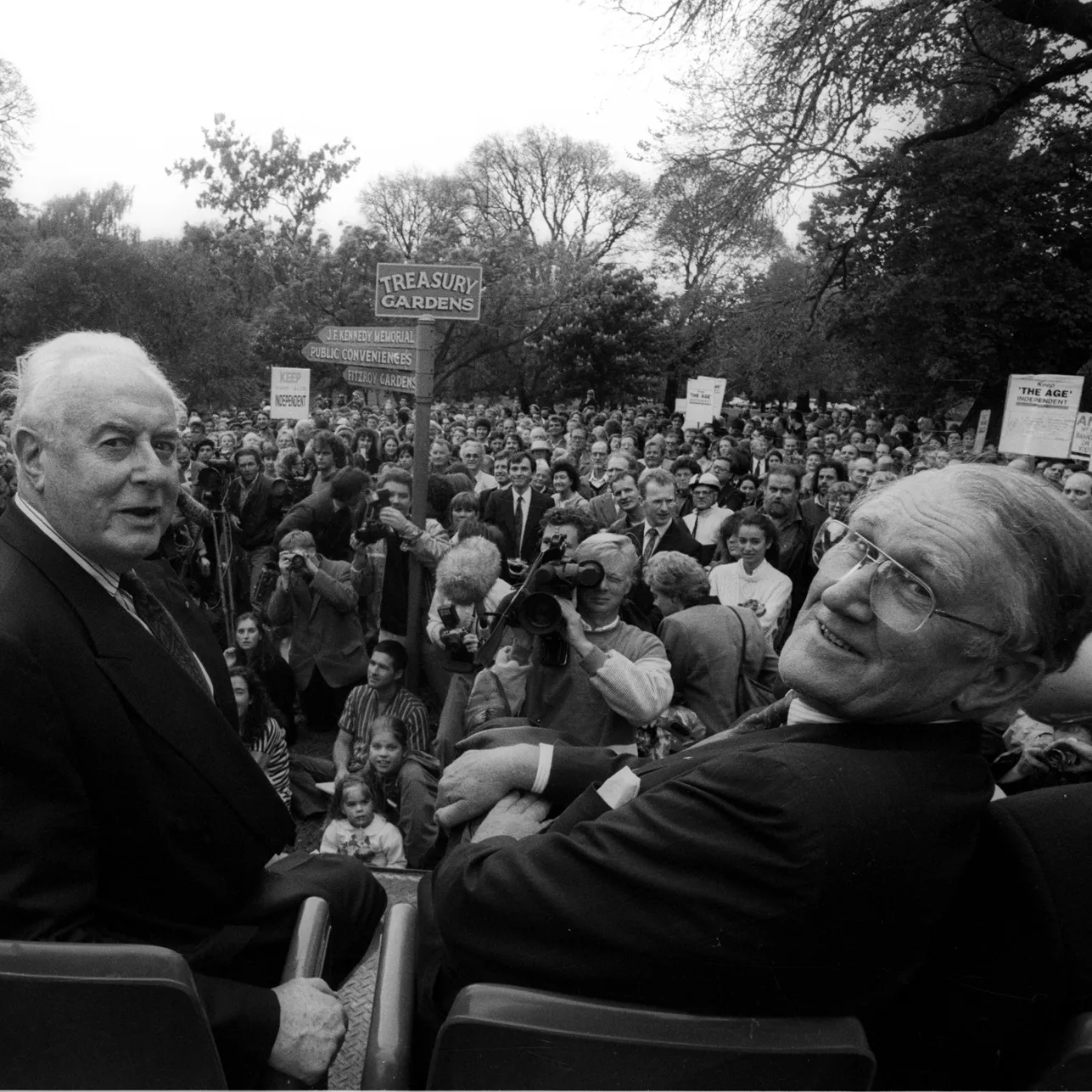

Dr Bob Brown campaigning for the Senate for the Australian Greens, 1995. Brown credited his medical career with forming many of his political views. Andrew Taylor/Sydney Morning Herald Courtesy of Fairfax Syndication