Breaking up is hard to do: secession in Australia

- DateFri, 27 Oct 2017

The abbreviation ‘Brexit’ has entered popular culture as a snappy term for the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union (a ‘British Exit’).

The term has been adapted for movements in other countries who hope to do the same thing, such as ‘Frexit’ (French Exit) and ‘Grexit’ (Greek Exit). The European Union is not a sovereign nation, so Brexit and similar movements aren’t really ‘secession’ in the same way that demands for independence in Scotland and Catalonia are.

Recently, the Western Australian chapter of the Liberal Party began opening a debate on secession, which they referred to as ‘WAxit’. While very unlikely to happen, it is actually possible, in theory at least, to split off from Australia and become an independent country.

All six Australian states were independent, sort of, before Federation. The six colonies were administered locally, but overseen by the British government. Though not truly independent, they each had their own local traditions, cultures and idiosyncrasies. For this reason, some people opposed the Federation of the six colonies, as well as for reasons of economics. After Federation, there have been sporadic movements in the states to withdraw from the Commonwealth of Australia and go it alone.

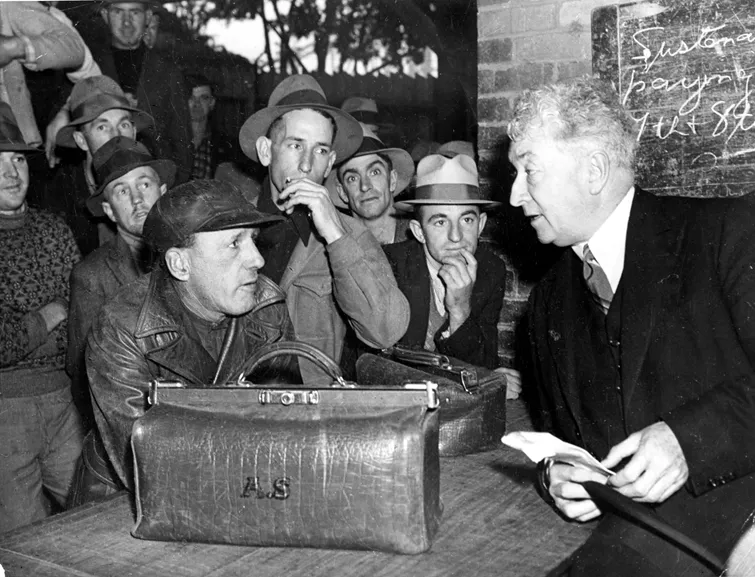

The most famous attempt, and the one that came closest to success, was Western Australia in 1933. The Nationalist government of Sir James Mitchell held a referendum on withdrawal from the Commonwealth. The reasons were complex, but largely economic. Secessionists felt WA was hit hardest by the Depression, and that the federal government wasn’t doing enough to help them. WA has always been a resource-rich state, with particularly strong wheat production and mining industries. In 1933, and since, some elements in WA believed their state was contributing more than its fair share to the Commonwealth and not getting enough in return.

Mitchell and the Nationalists campaigned for secession, while the Labor opposition under Philip Collier opposed it. In an unusual turn of events, the referendum passed by an almost 2-1 margin, but the Nationalists lost the election. Unwilling to go against such strong public opinion, Collier’s government submitted a petition to the British government.

That would have been that, but there was a major constitutional sticking point. The Australian Constitution defines the Commonwealth as ‘an indissoluble union’, which means it can’t be dissolved. The Constitution being an Act of the British Parliament, it was ultimately Westminster and not Canberra that had the right to decide the issue. After careful deliberation, a select committee decided that the secession was not lawful, and that the constitution would have to be changed first. The movement died down after that but, as recent news has shown, never entirely went away.

Speaking of Western Australia and wheat, another famous secession case is that of the Hutt River Province, now called the Principality of Hutt River. Wheat farmer Leonard George Casley had a dispute over wheat quotas with the WA government in 1970, and through a complex legal argument maintained that he had the right to secede from WA and Australia and form his own country. Styling himself Prince Leonard I, Casley has maintained his 75 km² ‘micronation’ to this day as a tourist attraction, minting his own coins and claiming as many as 18,000 overseas citizens.

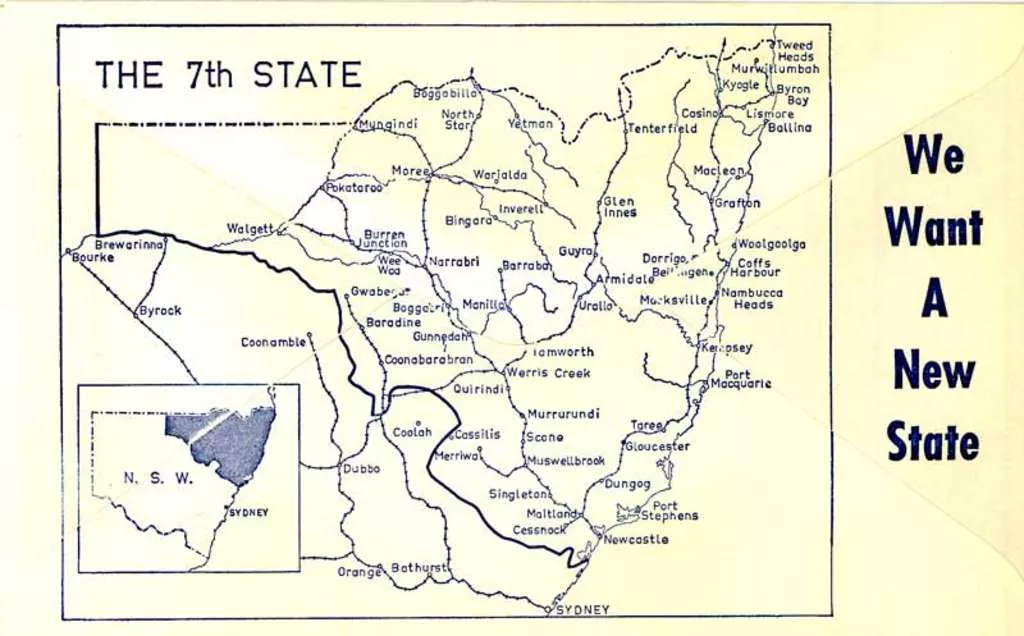

Proposals for new states, taking part of one state to form another, have also had some attention over the years. By far the most prominent example is the movement in New England, in northern NSW. Believing the area to be too far from Sydney to be effectively governed from the capital, New Englanders, including future prime minister Earle Page, argued for their own state stretching from the Queensland border as far south as the Hunter. The movement picked up speed after the Second World War and was most prominent in the 1950s, when literature and campaign material was mass-produced. The agitation eventually led to the state government holding a referendum on the separation in 1967. The NSW government included Newcastle and the Hunter Valley in the proposed new state, which was enough for 54% of voters to reject the proposal. The movement has been largely quiet since, although from time to time still crops up. Similarly, the movement to separate Far North Queensland as its own state has also been vocal on occasion. No referendum or serious proposal has ever been considered.

The 1967 referendum on New England statehood failed because many rural voters thought including Newcastle and the Hunter would be counterproductive. This envelope shows proposed borders, including Newcastle. Image: Museum of Australian Democracy Collection