Lowering the voting age

- DateThu, 24 Mar 2016

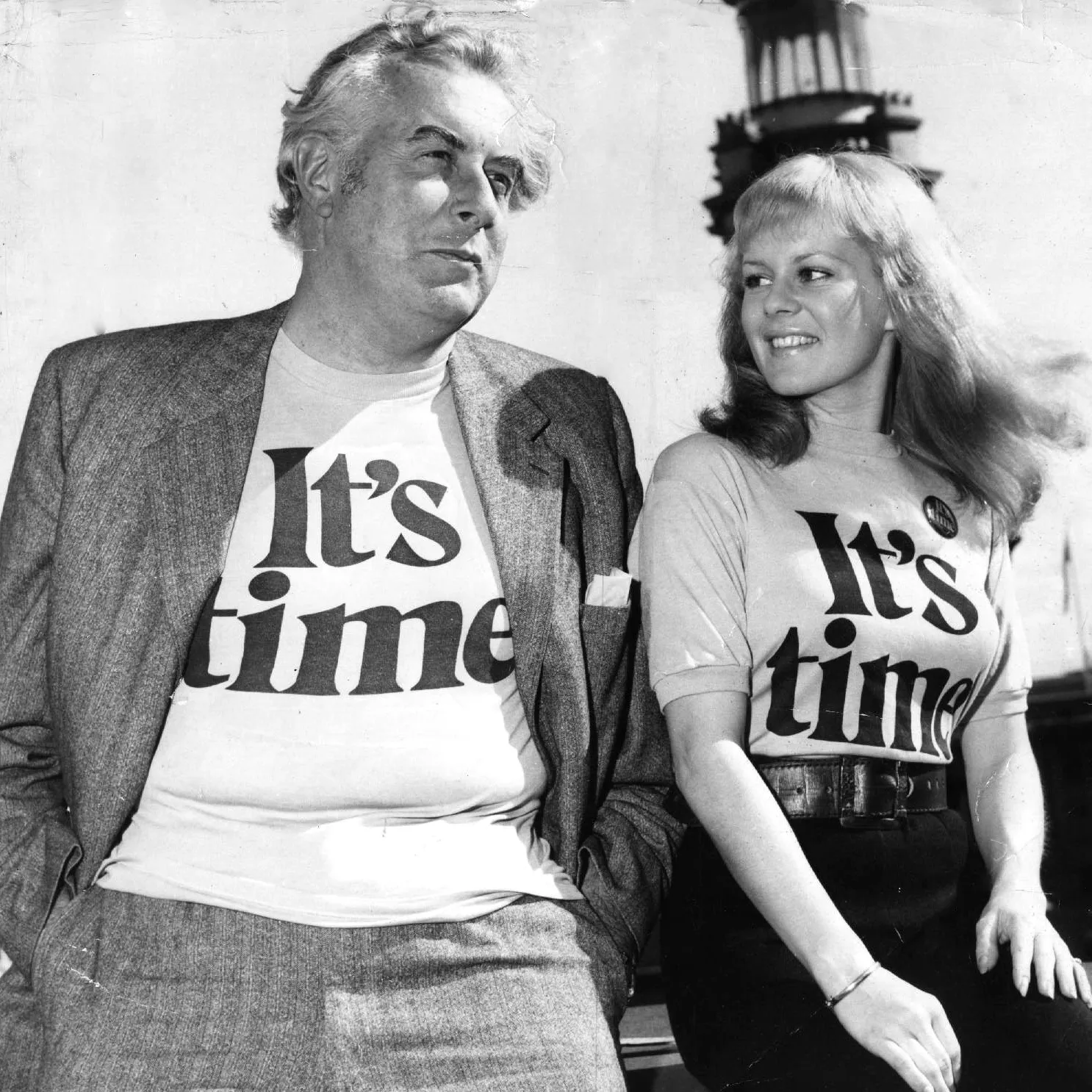

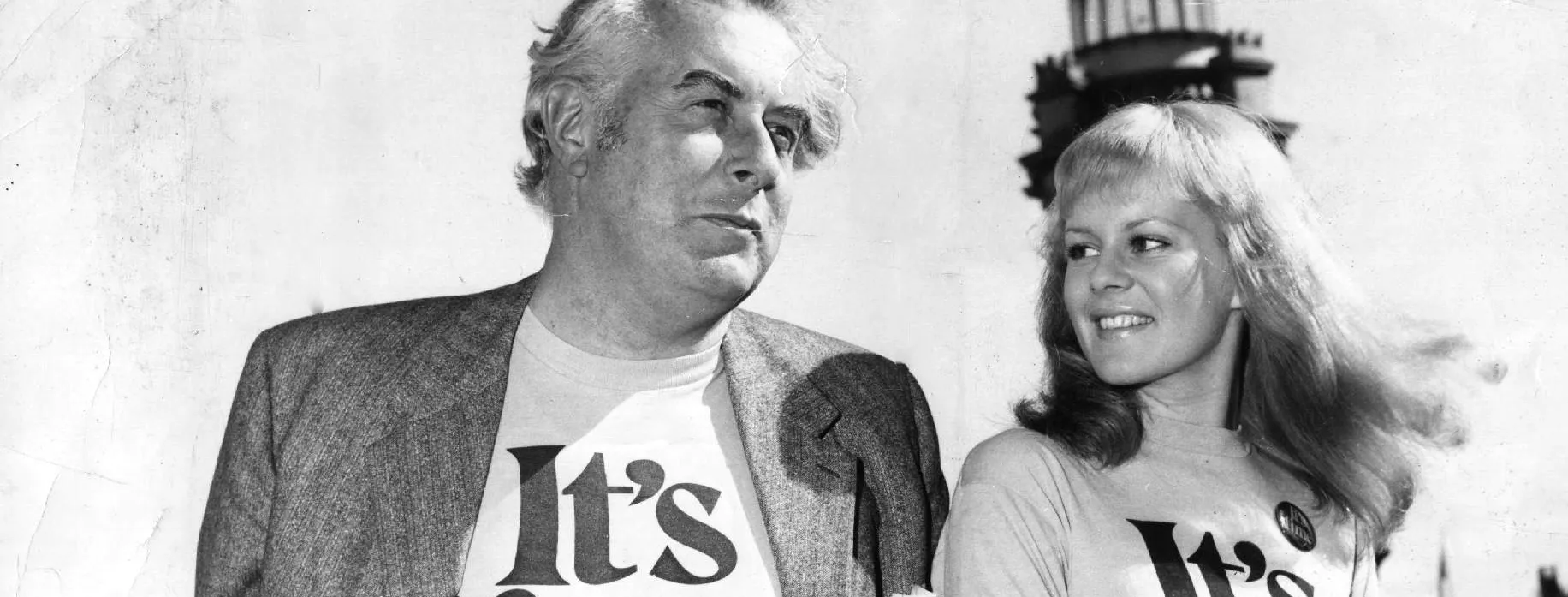

In 1973, Australia’s voting age was lowered from 21 to 18 by the Labor Government headed by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam.

It was a bi-partisan change, with the Commonwealth Electoral Bill 1973 having the support of the Parliamentary Opposition.

The Bill was debated in the House of Representatives on 28 February 1973; though the ‘debate’ really involved attempts at point-scoring as to why the Coalition had not supported such a reform during its previous 23 years in power. On the matter of principle and on the legislation, both sides were agreed.

Since Federation in 1901, the voting age for those eligible had been 21. An exception related to members of the defence forces serving in a war zone outside Australia; under special provisions they could vote in federal elections even if under the age of 21.

During the 28 years after the Second World War, nearly all Australians aged between 18 and 21 could not vote. Fred Daly MP, in presenting the 1973 Bill, described it as “an historic occasion… too long delayed”. He pointed to previous attempts to lower the age, in 1968 and 1970, that had been unsuccessful.

While Daly referred to “natural justice” in his case for the change, the argument was probably won by the reality of the new post-war demographics, changing perceptions and responsibilities of young people, and the precedents established by 35 others countries that had reformed their electoral laws to allow 18-year-olds to vote. In the United Kingdom, it happened in 1969 via the Representation of the People Act. In the USA, the change came in 1971 with the 26th Amendment to the US Constitution.

In the decades following the Second World War, Australia was undergoing rapid transformation economically, socially and culturally. A significant part of the change was prompted by the demographic factor known as ‘the baby boom’. After the War, there was a sudden spike in the number of babies born. The ‘Boomers’ were those born between 1946 and 1955. The lowering of the voting age added around 820,000 new voters to the electoral rolls for the 1974 federal election.

The social experience and expectations of this new generation were very different to those of their parents, who were mostly born in the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s. The baby boomers embraced a unique identity in terms of culture and, for a significant minority, politics. Thanks to the new invention known as the transistor radio, they could listen without supervision to rock music, with its sexual rhythms and occasional message of generational discontent and, in a period of economic prosperity, they could easily find paid work and break free from financial dependence on parents. Another new device, television, opened up the world to them as for no previous generation, as did the expansion and availability of air travel.

Australia’s under-21s were a numerically significant, somewhat noisy, ‘teen market’ who could marry and drive cars at 18, had unprecedented educational opportunities, especially at the tertiary level, and often worked and paid taxes. The idea of paying taxes without representation was anathema to the western democratic tradition, and indeed had sparked a few revolutions. However, it does not emerge as an important element in the parliamentary case for lowering the age.

In supporting the motion, Opposition Leader Billy Snedden recognized the reality of social and demographic change when he said that, compared to previous generations, young Australians were 'better informed, better able to judge, more confident in their judgements, more critical in their appraisals, and on more mature terms with society around them'.

Members of the ‘baby boom’ generation were the shock troops of a youth culture that was transnational in character and which, for some, expressed itself through political activism. Participants in street marches and demonstrations against conscription and the Vietnam war were mostly young people. Young men aged 20 had to register for national service, and the possibility of serving in Vietnam, but they could not vote.

Young people wanted to be heard and the established institutions were not adequately responding. Daly’s argument included a concern about the youth rebellion. He argued that lowering the voting age to 18 would 'remove one of the causes of discontent from the past. Our young people will be involved in the political life of the nation and will be able to direct their creative energies and enthusiasm to a better Australia'.

The 1973 Act also lowered to 18 the age of eligibility for candidature. Daly regarded it as 'one of the most far-reaching reforms within the Australian political community for generations'.