Prime Minister Harold Holt's 692 days as leader of Australia

- DateTue, 26 Jan 2016

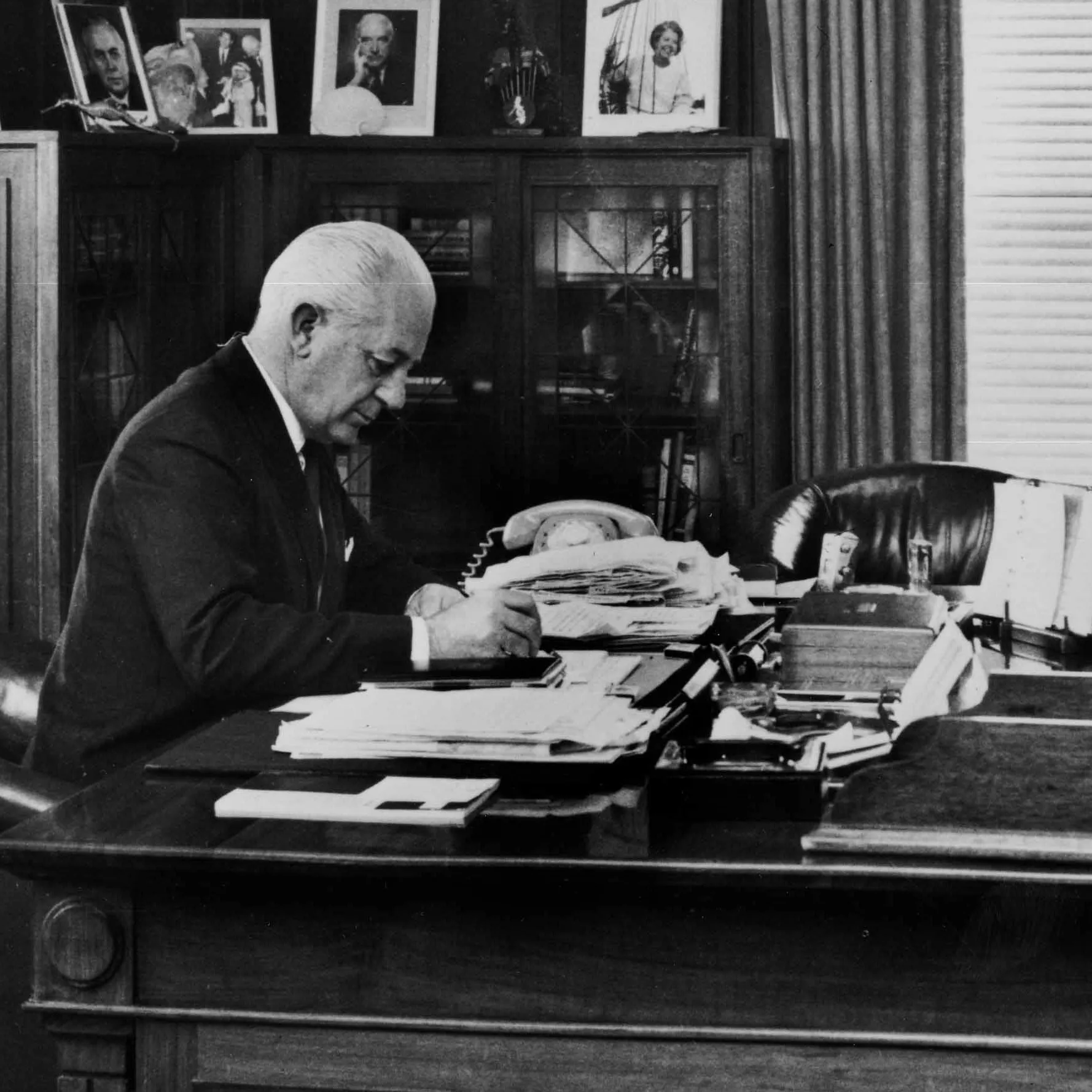

On 26 January 1966, Harold Holt became Australia’s 17th prime minister.

He took great personal satisfaction in his ascent to the role. As he explained to his wife Zara, he had not ‘stepped over anyone’s dead body’ to rise to the leadership of a nation that he believed could chart its own future.

Shortly after assuming office he told the Young Australian Foundation at the University of Melbourne that, while the nation once looked to Britain and the Royal Navy, ‘we have now realised that Australia is a national independent entity of its own and that Australia faces problems and has obligations which are quite unlike anything the earlier generations of Australians had to meet’.

While most Australians remember their 17th prime minister for the manner of his death and an ill-conceived remark to President Lyndon Johnson on the lawns of the White House in June 1966 that Australia would be ‘all the way with LBJ’, Holt’s 692 days as the nation’s leader changed the course of Australian life in seven key areas.

Holt identified Australia’s need for a regional focus. His inaugural overseas tour was to Asia and within twelve months of assuming the role of prime minister he had visited ten Asian countries; he was the first Australian prime minister to visit Cambodia, Laos, Taiwan and South Korea. Holt stressed Australia’s commitment to regional economic development through the Colombo Plan and the Asian Development Bank, and identified South East Asia as a ‘critical battleground for free peoples’. His visits were designed ‘to make Australia and its policies better known … Geography brings us together and, at the same time, there are mutual interests to be served’.

Harold Holt also pioneered the promotion of Australia’s unique place in the world. With an end to the formative years of nationhood within the British Empire, ‘adulthood’ had been thrust upon the country. Holt initiated the abolition of appeals from the High Court to the Privy Council in matters of Federal jurisdiction and, in August 1967, he directed that the word ‘British’ be dropped from Australian passports while ‘British subject’ was deleted from the Nationality and Citizenship Act.

Further, Holt insisted that Australia assert its economic independence. When the United Kingdom’s Wilson Labour government devalued the British pound, Holt defied his Coalition partners and tradition. He stated: ‘The Australian dollar is a currency in its own right. It has to stand on its own feet and it has shown itself capable of doing so. We have an enviable reputation abroad for political and economic stability … It is, of course, one thing for us to take the decision and another thing to live with that decision. It was imperative that we do nothing to undermine confidence in the Australian dollar’. The Bulletin noted the decision was ‘quite certain to mean the end of any remaining special relationship between Australia and Britain’.

As prime minister, Holt also began to dismantle the White Australia policy. Within three weeks of assuming office, the Cabinet re-examined proposals to change the immigration laws that Prime Minister Menzies rejected in 1964. The most significant shift was a provision to allow a number of ‘temporary resident’ non-Europeans to become permanent residents and citizens after five instead of fifteen years. This created parity with European migrants. The Government also assisted in family reunions and eased restrictions on immigration of certain ‘well qualified’ non-Europeans. Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman of Malaysia said Australia had shown a genuine ‘desire to be more friendly with Asian countries’. The Adelaide Advertiser pronounced that Holt ‘may not have finally buried the White Australia policy’ but he had given it ‘a decent covering’.

In addition, Harold Holt recognised that the Federal Parliament needed to show leadership in Aboriginal affairs. After a referendum in 1967 gave the Commonwealth power to legislate in relation to Aborigines, Holt visited urban and rural communities, met leading indigenous figures like Charles Perkins, and read whatever he could obtain on Aboriginal history and culture. Holt then established the Council for Aboriginal Affairs. Its role was to ‘advise the Government in the formulation of national policies for the advancement of the Aboriginal citizens of Australia’. On realising the presence of discrimination and the extent of indigenous disadvantage, Holt applied his personal authority to ensure the Council’s policy initiatives were implemented and real improvements were achieved.

Support for the arts and cultural bodies became a key Commonwealth responsibility under Holt. Dr H C ‘Nugget’ Coombs persuaded the prime minister that the arts needed a broader government agency than the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust. In late 1967, Holt established an Australian Council for the Arts under Coombs’ direction with the task of coordinating policies and devising programs that could benefit from Government support.

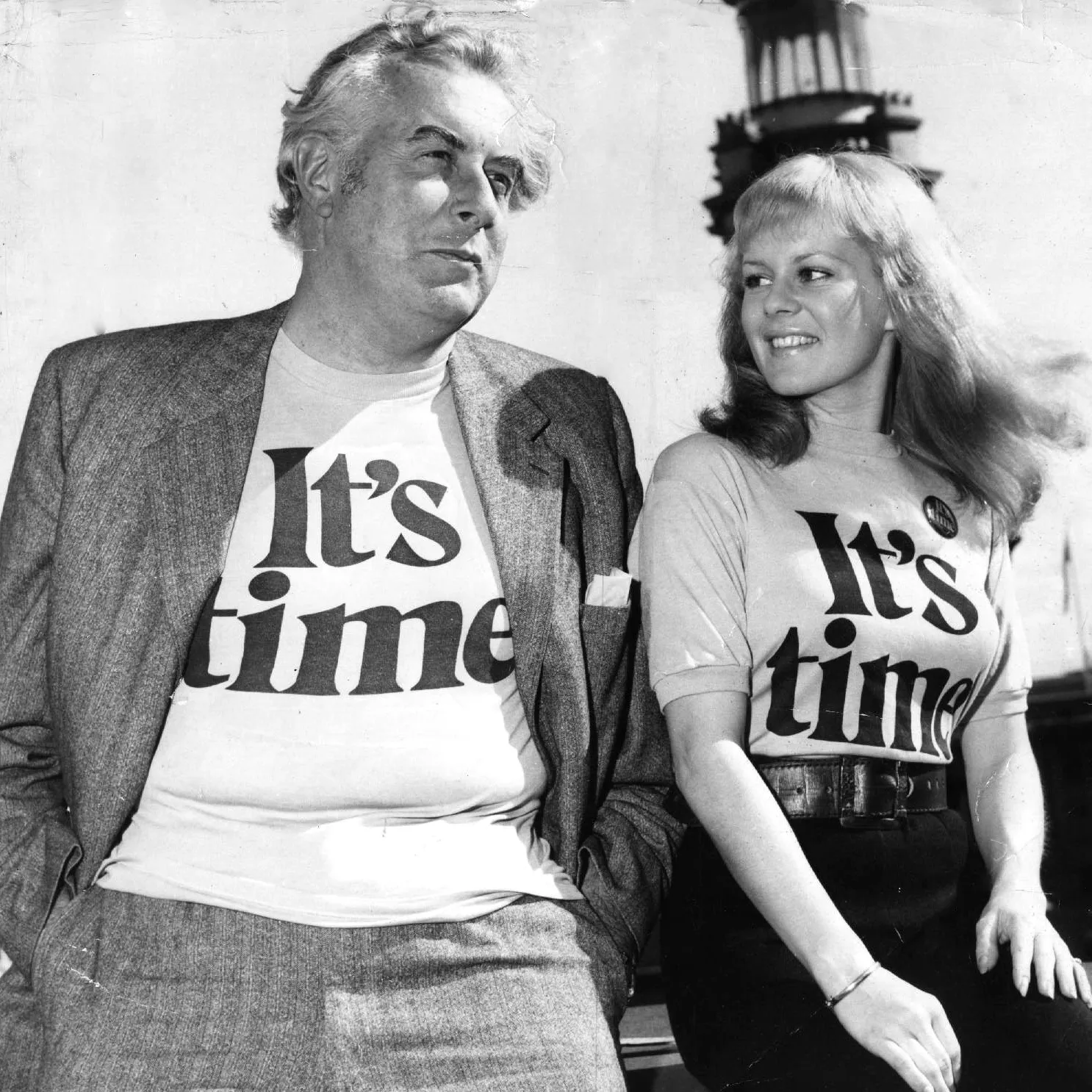

Harold Holt disappeared while swimming on 17 December 1967. His presumed drowning created a crisis in the Liberal Party that, after the ‘Gorton Experiment’, led ultimately to the succession of William McMahon to the prime ministership. Although McMahon is widely considered to be Australia’s poorest prime minister - Labor’s winning margin in 1972 was a mere eight seats - the Liberal Party did more to lose government in 1972 than Labor did to win. It was not until 1975 that the Liberals found in Malcolm Fraser a leader who could deal with parliamentary dissidents and reinvigorate a divided party with a diffuse philosophy.

When the Federal Parliament passed a condolence motion following Holt’s disappearance, Opposition Leader Gough Whitlam offered a very generous tribute recognising his many achievements. He said the key to Holt’s ‘ability to establish relationships with men of different backgrounds, attitudes and interests was his essential decency. He was tolerant, humane and broadminded. His suavity of manner was no pose. It was the outward reflection of a truly civilised human being. He was in a very real sense a gentleman.’

Holt’s death unfairly overshadows his life, his political career and his prime ministership. Now, more than 50 years after assuming office, he ought to be remembered for encouraging the country towards a greater sense of social self-awareness, economic independence, national maturity and international pride.