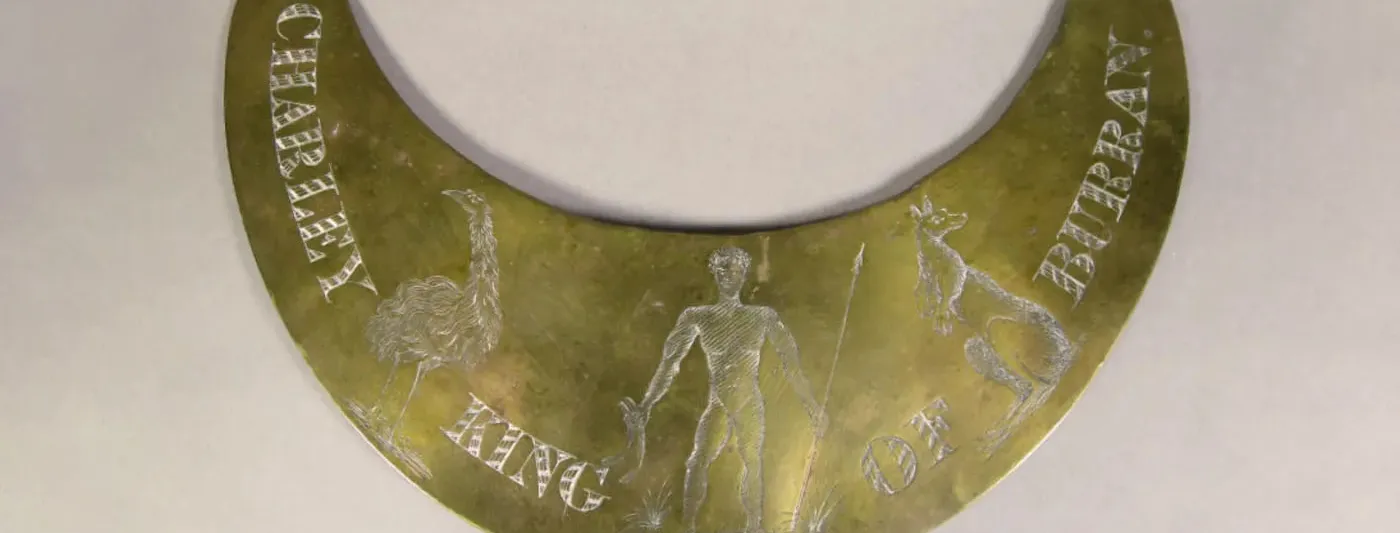

Charley’s choice: the breastplate of Charley, king of Burran

- DateThu, 23 Feb 2017

William Ridley was a Presbyterian minister with an epic beard and an ear for languages.

First nations people are advised that this article contains the images and names of deceased people.

In the 1850s he served as a missionary to the Gamilaraay and neighbouring peoples of northern New South Wales. His record of the languages and stories of the Kamilaroi, Dippil and Turrubul was published in 1866 and a second edition, Kamilaroi and other Australian Languages, was released in 1875. More than 140 years later, something he wrote caught my eye.

‘When I first went down the Namoi [River], in 1853,’ Ridley wrote, ‘I saw there an old blackfellow named Charley, of whom the early settlers told this narrative:

"On the first occupation of that part of the country by squatters, Charley was the leader of a set of blackfellows who greatly annoyed them by spearing cattle. Many attempts were made to cut short Charley’s career with a bullet; but he was too active to be overtaken, and too nimble to be made a target of.

One day a stockman pursued him a long way with a pistol, but could not get a successful shot at him. Shortly afterwards the same stockman was travelling unarmed through the bush when his horse was knocked up, and he had to dismount and try to drag the weary brute after him. While he was in this plight a number of blackfellows suddenly sprang out of the bushes and surrounded him. At their head was Charley.

The stockman thought he was now to die…"'

Museums are full of objects and objects are full of stories: of places, environments, events, economies, societies, people and their ideas and values. One of the museum curator’s roles is to find these stories and explore their meaning. Our museum collection holds some breastplates presented to Indigenous Australians. Breastplates were a feature of the colonial era, and say much about cross-cultural relations of the time. Many are the only remaining tangible records of lives caught in massive upheaval. As unique proof of a named Indigenous person from this period, breastplates thus tell the most important story: that the person existed.

Charley’s world

But who were they? It can be hard to tell. Given the lack of records, evidence is often circumstantial. When I found Ridley’s account I realised the Namoi River flows near Burren Junction. Charley was therefore almost certainly the man whose name is engraved ‘Charley, King of Burran’ on one of the breastplates in our collection. I had struck gold: an insight into Charley’s world.

Charley’s own Gamilaraay name is not yet known to me. It’s possible he acquired his English name from Charles Button, a recruit of the Australian Agricultural Company who left England in 1837 with his wife Elizabeth and baby John. In 1843 Button got a license to graze stock on Charley’s country, the Liverpool Plains of New South Wales. In 1848 he claimed a lease of 38,400 acres called ‘Burran’ near what is now Burren Junction, between Walgett and Narrabri.

Burran is Gamilaraay for ‘boomerang’ and it describes the shape of the big creek bending through the grasslands. But Charles’ pasture was Charley’s carefully crafted hunting ground, and it seemed neither man was going to give it up without a fight.

When the British colonists arrived, the laws and practices of Indigenous Australians were largely misunderstood, disrespected or ignored. Contact often led to conflict. Major-General Lachlan Macquarie, Governor of New South Wales from 1810 to 1822, attempted to resolve this conflict by incorporating Indigenous people into colonial society in several ways.

One method was to select from each group a ‘chief’, ‘king’ or ‘queen’ assigned to control the group and act as an intermediary for colonial officials. This leader—who may not have held equivalent authority within their own society—was identified by an engraved metal breastplate, worn around their neck. Breastplates derive from the gorgets worn by British Army officers in the 18th century to indicate rank and regiment. As a teenager Macquarie had seen them presented to First Nations peoples in colonial North America, where he served in the American Revolutionary War.

Frontier encounter

By the 1830s squatters and settlers were deploying breastplates on Australia’s increasingly war-like pastoral frontier. Breastplates identified influential local people who helped the newcomers’ endeavours and provided protection for them and their stock. (This explains why breastplates are also engraved with the name of the pastoral run.) Breastplates also recognised an Indigenous person’s labour, loyalty or heroism. Is this why Charley had one? William Ridley continues:

'The stockman thought he was now to die; but instead of spearing him, Charley addressed him in this manner:

"You ’member blackfellow, you chase’m with pistol, you try shoot him. I that blackfellow, Charley! Now me say I kill you; then me say bel (not) I kill you; bel blackfellow any more coola (anger) ’gainst whitefellow; bel whitefellow any more coola ’gainst blackfellow! You give me ’bacca."'

Reproduced by Ridley for a non-Indigenous audience, Charley’s words and their meaning may have been simplified and compromised. Nevertheless, Ridley’s third-hand and perhaps crudely paraphrased account of frontier diplomacy is a rare record of an Indigenous man’s point of view.

There seems no reason to doubt the veracity of Ridley’s account: like all reasonable people, Charley probably had no desire to kill a fellow human. On the other hand, it’s easy to imagine that after months of evading murderous pursuit Charley may have been tempted to retaliate. Yet when the opportunity presented itself, he called a truce. Perhaps he was worried about the payback that would have been wreaked upon his own people if he had killed the stockman. Ridley continues:

'So he made friends with the white men; and from that time was a useful neighbour and often servant to them—protecting their cattle and minding their sheep. Like many a blackfellow who was at first an enemy and afterwards a steady friend, Charley made the settlers know that his word could be relied on.'

Without Charley here to elaborate, it’s necessary to impose an interpretation of his actions. My interpretation is informed by the context of these actions and is, I hope, ethical and accurate in spirit.

Survival as resistance

It seems Charley’s choice to cooperate with the newcomers brought him some level of power within the limits of colonial society. It could be argued that his cooperation was coerced by circumstance and his power was hollow, given it undermined established authority within Indigenous social structures. Breastplates are now often regarded as symbols — even tools — of dispossession and oppression.

But Charley at least secured some level of protection for his people and some access to his country, however circumscribed. (Indeed, native title claims have added to the significance of breastplates as evidence of ongoing connections to land.) Rather than being the passive recipient of the breastplate, Charley may have observed the relative ‘advantages’ breastplates gave to other Indigenous people. He may have chosen to modify his behaviour in order to get one, as a matter of survival. And survival is a form of resistance.

Given the date of Button’s claim and Ridley’s account, Charley may have received his breastplate in the late 1840s or early 1850s. The design of his breastplate is fairly standard: the brass blanks were mass-produced, indicating the extent of the practice, and kangaroos and emus are common motifs. A local blacksmith or watchmaker engraved the personal details on each breastplate as required.

But it’s nevertheless fitting that the illustration on Charley’s breastplate depicts a man carrying a spear and two burran. King Charley may not have been a real monarch, but he was a real person who faced routine terror with pragmatic heroism. His breastplate documents his efforts to adapt to his rapidly changing world.