War and unity: how Australia governs during a crisis

- DateFri, 27 Mar 2020

How does Australia govern itself during a major crisis, and how does it maintain its democratic norms during something like the COVID-19 pandemic?

First Nations readers are advised this article contains the name of a deceased person.

As events in 2020 unfolded, the government unveiled all sorts of measures, but in all the hubbub of media, one may have missed some of the detail about what was happening.

There can be a lot to unpack in these announcements, but there is some important historical context to what's happening. To understand how the government is working during the pandemic, you can look at some things that have been done in the past.

What’s this National Cabinet the PM keeps meeting with?

It’s different from the Cabinet, which consists of Scott Morrison’s senior ministers. The National Cabinet is a meeting between the prime minister and his state and territory counterparts, the Premiers and Chief Ministers.

Normally, the meeting of state and territory leaders, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), meets once or twice a year to discuss major issues. There is no legal effect or constitutional basis for any COAG meeting or decisions, but the body can and does exert influence over national approaches to complex problems.

In this particular situation, National Cabinet are making decisions collectively, much like the Cabinet does, which are then implemented by governments around Australia.

So, is that like a War Cabinet?

Only in as much as it is sometimes called that by the press. A War Cabinet, as the name suggests, is a body that some countries, including Australia, have had during wartime - specifically World War I and World War II.

What is a War Cabinet then?

A War Cabinet is a body formed to co-ordinate a national wartime effort, from military operations to rationing and even censorship. While most countries during wartime continue to have a normal cabinet as well, a War Cabinet is a special body, specifically designed to make decisions relevant to the war. During World War II, such cabinets were formed in the United Kingdom, and they were also formed during the Falklands conflict and the Gulf War. The United States created a War Cabinet to prosecute the ‘War on Terror’ after the September 11 attacks.

Has Australia ever had a War Cabinet?

Yes, it did. In fact, it had more than one!

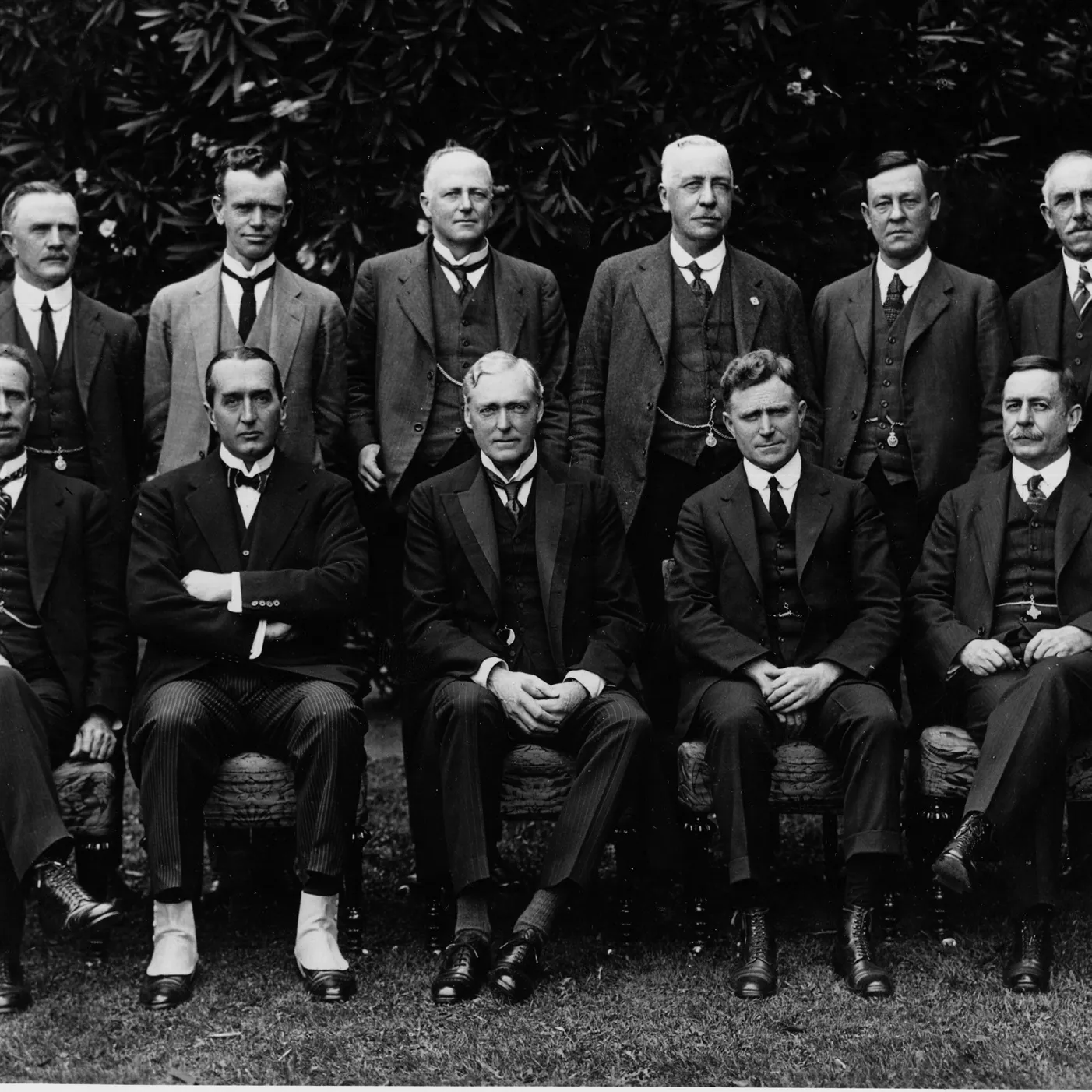

At the beginning of World War II, Prime Minister Bob Menzies convened a War Cabinet to handle wartime co-ordination. Its first version consisted of Menzies himself and some of his most senior colleagues, including Defence Minister, Geoffrey Street, Supply Minister Richard Casey, Commerce, Information Minister Henry Gullett, and Attorney General Billy Hughes.

After Street, Gullett and another War Cabinet member, James Fairbairn, were killed in a plane crash in August 1940, new ministers Arthur Fadden, John McEwen, Percy Spender, and Philip McBride took their places in Menzies’ War Cabinet. All this time, the regular cabinet continued to meet and make decisions that were not directly connected to the war.

When Arthur Fadden took over from Menzies as Prime Minister in August 1941, he continued Menzies’ War Cabinet. Forty days later, John Curtin took office when Labor came to power, and a new War Cabinet was convened. Like Menzies’ version, it consisted of the most important and senior members of the government, including Ben Chifley (Treasurer), Doc Evatt (External Affairs and Attorney General), Norman Makin (Navy & Munitions) and John Dedman (Interior). Throughout all incarnations of the War Cabinet, its Secretary was Sir Frederick Shedden, Secretary of the Department of Defence, a public servant.

What is a national unity government?

One key difference between wartime politics in Australia and Britain was that Britain, during both World Wars, operated under what they called a National Government, also known as a Unity Government or a Government of National Unity. These are very rare in politics, but during major wars they were common in many countries. A unity government is one in which partisan differences and even party politics are largely suspended, and the two biggest parties work together as part of the same government, often including others as well. In peacetime, this is sometimes called a Grand Coalition and is the current norm in Germany and Iceland, and have often been seen in Austria and Israel. While Scott Morrison’s National Cabinet is bipartisan, in that both Labor and Liberal premiers and chief ministers are part of it, it is not a government of national unity since the Opposition Leader, Anthony Albanese, and the federal Labor Party have no formal involvement, and partisan politics is continuing.

Has Australia ever had a bipartisan government?

Australia has never had a true government of national unity. Robert Menzies, while prime minister before WW2, proposed such a thing to Labor several times, only to be rejected. Others also proposed it, including Sir Earle Page, who even offered to resign and allow Stanley Bruce to re-enter parliament so he could lead an all-party government. These discussions came to nothing, and the war went on with party politics perhaps a little less bitter, but still very much a reality. The closest Australia got was the Advisory War Council, established during World War II, which had members from both major parties.

What would happen if there was an election at the same time as a pandemic?

Australia’s Constitution is very specific that elections must be held at least every three years, and the need for one can’t be ignored, even during wartime. During World War I, some politicians including Billy Hughes himself proposed that elections be postponed, or at least all current MPs be elected unopposed, so that the war effort could continue uninterrupted. This never eventuated, and in 1917 Australia went to the polls with the war raging in Europe, resulting in a landslide for Hughes’ Nationalists. The same situation repeated in 1943, where the potential Japanese threat to Australia led some to propose postponing elections. They nonetheless went ahead, and Curtin’s Labor government won its biggest-ever majority.

It is unclear whether the government could temporarily suspend or delay an election, even during a crisis. Any attempt to do so would probably be sent to the High Court, as it could conflict with the constitution.

Advice from outside

The Morrison government also established a 'coronavirus commission' of business, union and public service officials to help co-ordinate the ongoing economic and social impact of the pandemic. While unusual, it was not without precedent for governments to gather people from outside politics, especially the world of business, to provide advice and assistance.

During World War II, journalist and newspaper magnate Sir Keith Murdoch was appointed as Director-General of Information. Murdoch, the father of media mogul Rupert Murdoch, was given the government job as head of a fairly powerful agency, and acted as a kind of wartime censor and media regulator. He was immediately unpopular with his fellow media figures, however, as he began to compel newspapers to print corrections in news, which they saw as an attempt to make them follow the government lines. He was even compared to Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebells, and after less than a year resigned his post.

A co-operation of a different nature was instituted by the Hawke government when it came to power in 1983. It set up a National Economic Summit, between the business community, the government, and the union movement. The summit, convened in the House of Representatives, brought together these delegates to hammer out agreements on wages, inflation, unemployment and a general economic strategy. Hawke remained very proud of the work done at the summit, and continued to talk about it for years as an example of his government's consensus-driven approach to major policy issues.

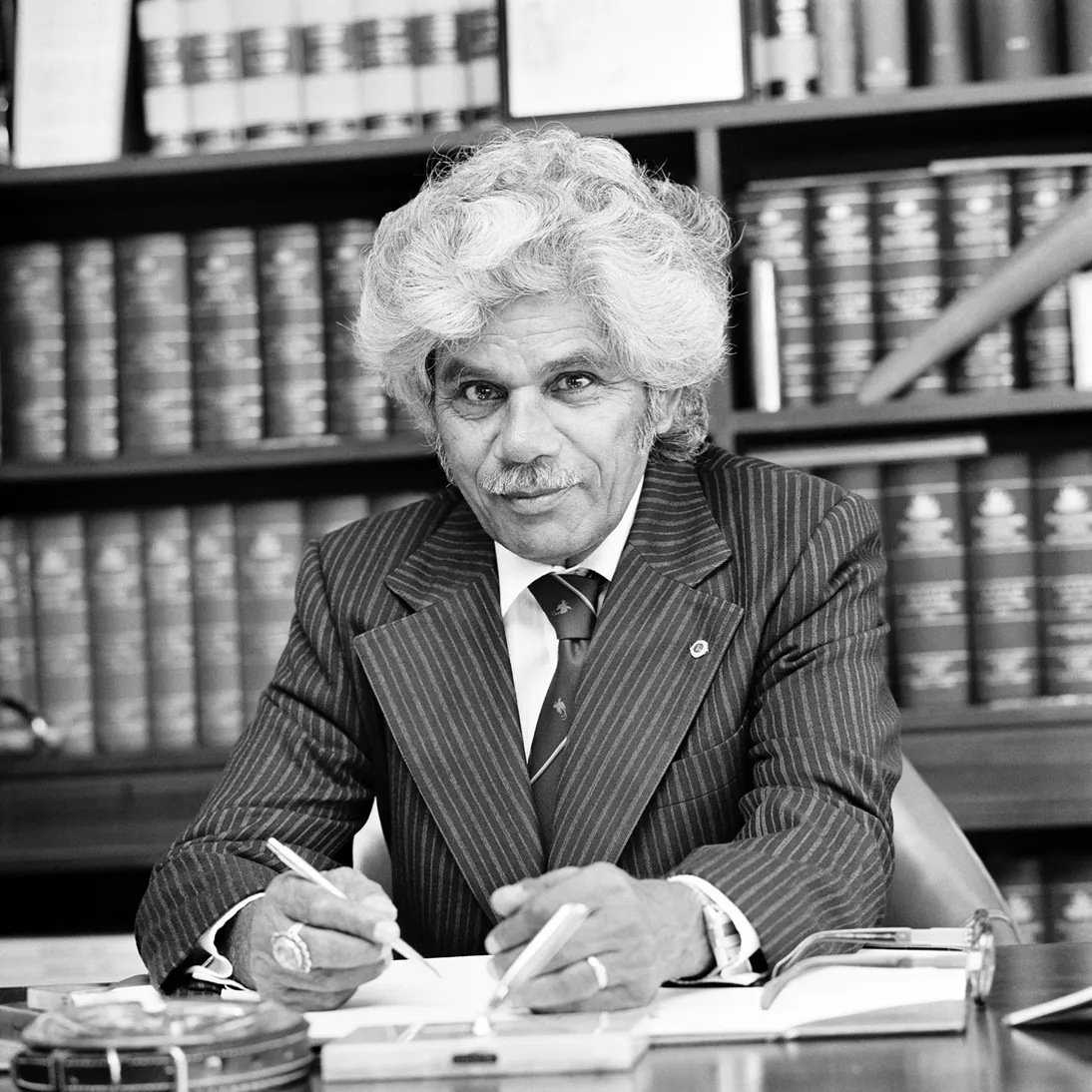

When the Rudd government came to power in 2007, it organised the '2020 Summit', a meeting of business, arts, government, academia, journalism and churches, among others, were gathered in Canberra. The purpose of the summit, according to Kevin Rudd, was to provide a long-term strategy and vision for Australia's future. Delegates included mining executive Andrew Forrest, former High Court judge Mary Gaudron, Indigenous leaders Noel Pearson and Pat Dodson, musician and activist Mandawuy Yunupingu, and actor Rhys Muldoon. Whether the summit produced a significant result is a matter of debate; in some sectors it was praised for its inclusivity and innovation, while others derided it as a 'talk-fest'.

What now?

There’s a lot happening at the moment, some of it precedented and some of it not. The situation around COVID-19 keeps changing, and the ways society and government are adapting are changing just as fast. Australia’s government institutions are robust, and can, with some challenges, adapt to the ever-changing world and function effectively in a crisis.