Wearing your politics

- DateTue, 07 Jun 2016

In a robust democracy, you can walk down the street wearing the colours and symbols of any candidate or organisation you desire.

Australians have embraced this as a tradition, and every election is filled with all the colours of the rainbow as supporters emerge to spruik their candidate or cause. You’ve probably seen them when you’ve gone to your local shops. A candidate is standing for election and is handing out leaflets, talking to voters. And around them, a small crowd of supporters, wearing eye-catching t-shirts emblazoned with the name of the candidate and/or their party.

What you wear can be a powerful statement. Even a t-shirt that doesn’t expressly endorse a candidate or party can be an act of democratic protest or rebellion. Everything can be political, and the right to express your views however you choose is an important one in any democracy.

Earlier in the election campaign, the Museum shared some examples of its badge collection that promote parties or candidates. A badge, though easy to make, is also easy to miss. But it’s hard to miss someone in a t-shirt; they’re a much more obvious way to show your colours and support a party of your choice. In this post, we want to show some examples of t-shirts (and one skivvy) from our collection that make the most democratic of statements.

This shirt belonged to Senator Christine Milne, leader of the Australian Greens from 2012 to 2015. Senator Milne wore this shirt at campaign events (and maybe around the house, who knows?) at a time when the Greens were becoming the most successful third party in decades. Milne had been there almost since the beginning, elected to the Tasmanian parliament in 1989 alongside the Greens’ most well-known figure, Dr Bob Brown. She succeeded him as the Tasmanian party leader in 1993 and followed him into the Senate eleven years later. She was the natural choice to succeed him as leader of the federal Greens. In 2013 the Greens, under Milne’s leadership, won more seats in the Commonwealth Parliament than any minor party had done since the early days of federation, with ten Senators and one Member of the House of Representatives.

Seeing someone walking down the street in a bright yellow T-shirt labelled ‘Palmer United’, you might be forgiven for thinking someone had started a new football team. The distinctive yellow colour is eye-catching and a contrast to the traditional red and blue of the major parties, or the green of the Greens. Mining magnate Clive Palmer’s new party was launched in 2013 as exactly that; a contrast to the traditional parties. Palmer’s name recognition and fundraising ability meant the party enjoyed some success; at the 2013 election, it won three seats in the Senate, and Palmer was elected to the House of Representatives. Palmer United are one of a number of modern parties that have tried to break into politics and challenge the domination of the older, established Liberal and Labor parties. Interestingly, when Palmer formed his party he initially did so as a continuation of the pre-war United Australia Party; the name was later changed to avoid confusion.

Just after Kevin Rudd became Prime Minister, the Museum put in a temporary update to its Prime Ministers of Australia exhibition, with a framed photo of Rudd and the date. Almost as soon as it went up, we were stunned. Teenage girls were flocking to it to have their photo taken with it, or to do a selfie. They would touch it, and a few of them even kissed it. That exactly how effective the Kevin 07 campaign was. The first election held in the age of social media meant the simple slogan went viral. Already well-known from his appearances on morning television show Sunrise, the campaign made Kevin Rudd a celebrity of rock-star-like appeal, and the tide of electoral support for Labor saw him swept into the Lodge after 11 years of a Liberal-National government. At the time, nobody predicted how the next six years would unfold. But the Kevin 07 slogan and campaign remains the ‘It’s Time’ of the selfie generation.

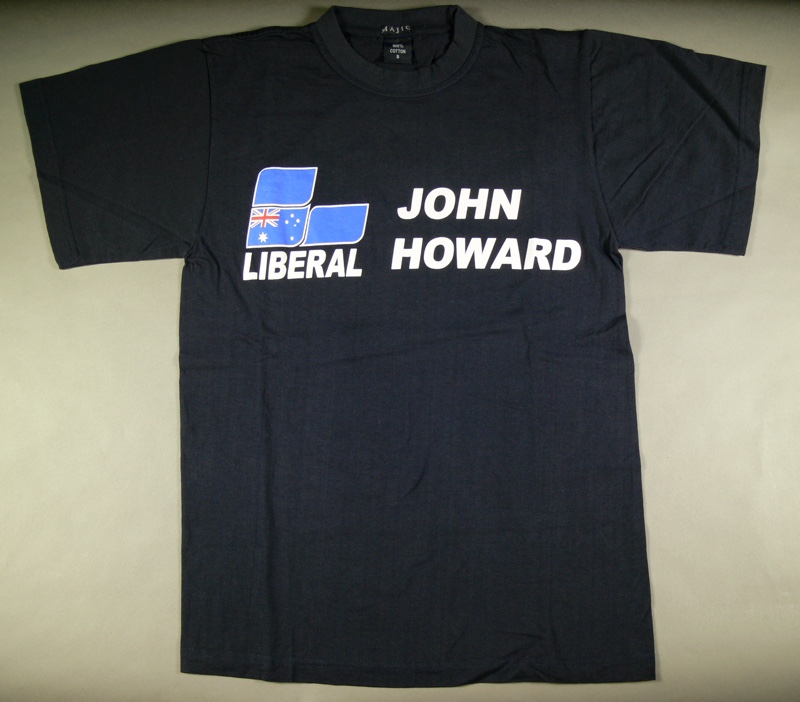

Winning a seat in Parliament is hard. Candidates work tirelessly to scrape together the votes they need to get them over the line. Their supporters work equally hard, so even if they lose, election night comes as a big relief. It probably wasn’t, however, a huge relief for John Howard and his supporters on the night of 24 November 2007. On that night it looked like Howard was about to become the first sitting prime minister to lose his seat in almost eighty years. Howard was a popular and active local member. But it’s hard enough to win a seat in Parliament if you’re a backbencher, so imagine how hard you have to work to do it while also being prime minister. With a high-profile opponent, former ABC journalist Maxine McKew, Howard had to work even harder, and his supporters came out in droves to support their leader and keep him in the Parliament. It was, ultimately, a bitter defeat for Howard, but the loss wasn’t for lack of hard campaigning and a strong, loyal group of backers pounding the pavement on his behalf.

If you’re above a certain age, you might remember an advertisement for the Yellow Pages in which a character called Jan forgets to put her boss’s business in the phone book. “Not happy, Jan!” screamed her boss, as Jan beat a hasty retreat. That line became a meme of its day, and in 2004 journalist Margo Kingston used the name “Not happy, John” for her book about what she saw as the failings of John Howard’s government. This slogan also became a meme, and was used particularly as part of a campaign to unseat Howard in his own electorate, Bennelong. This shirt, which belonged to and was worn by Senator Natasha Stott-Despoja, uses that slogan and the Australian Democrats logo to communicate its clear message: get rid of John Howard, vote for us. In 2004 it failed, but just three years later Howard did lose his seat, to journalist Maxine McKew from the ALP.

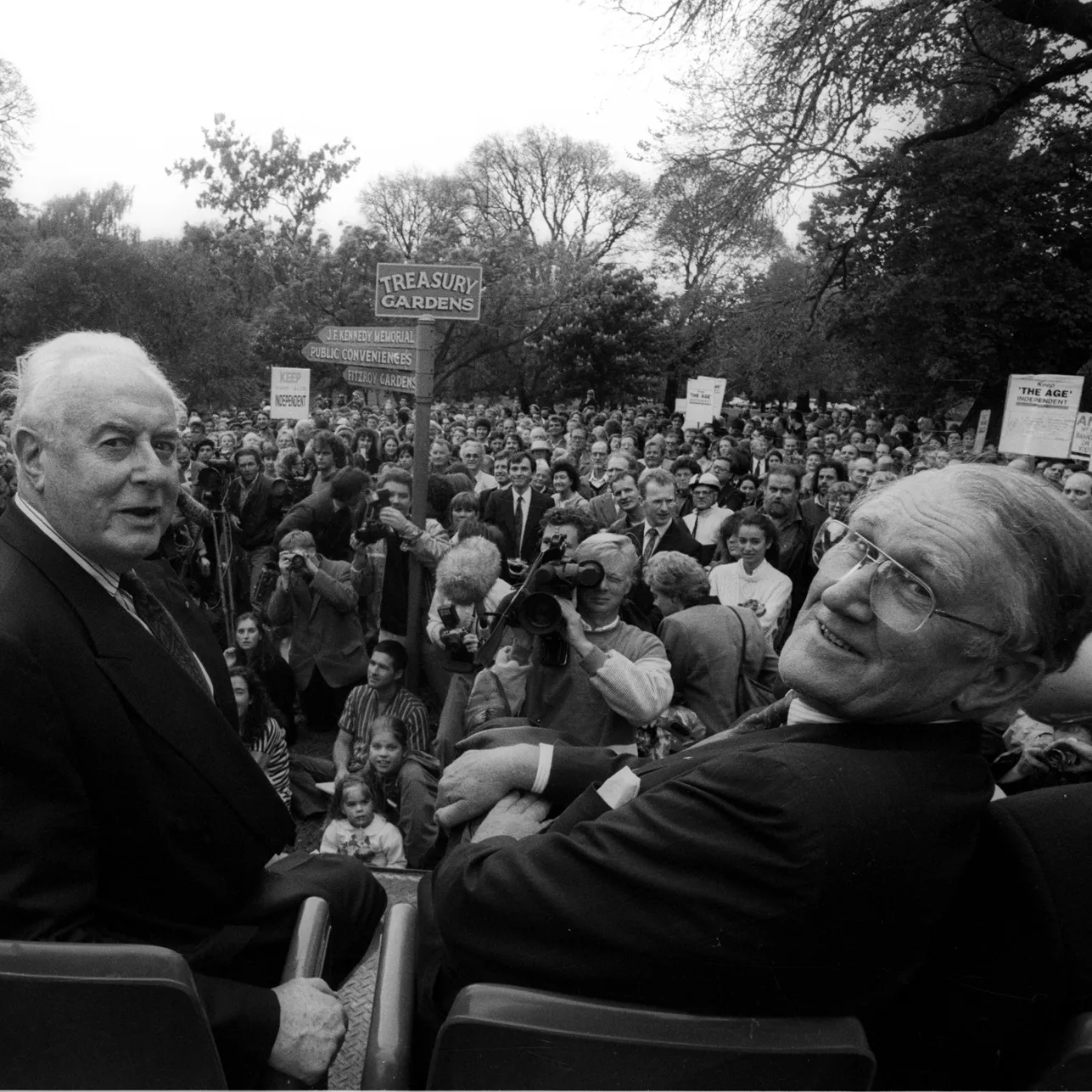

A common complaint made by Australian voters is that they are asked to choose between choose between several candidates (or parties), none of whom they like. Of course that’s common in any democracy, but in Australia and a few other countries, voting is compulsory. You don’t have to cast a valid vote, but for some people their vote is a way of channelling Mercutio: ‘A plague on both your houses’. In 1996, Albert Langer of the group ‘Neither!’ proposed to vote in such a way that preferences wouldn’t flow to either the Labor or Liberal parties. Technically, such a vote was valid, but under the Commonwealth Electoral Act it was an offence to advocate it. The Victorian Supreme Court ordered him to stop and, when he refused, Langer was jailed for ten weeks. On appeal to the Federal Court, Langer was released. Did his argument have any effect? At the 1996 election informal votes went up by 500% over the previous poll. The law was then changed, to make sure votes like Langer’s wouldn’t be counted, but also to repeal the section under which he was charged. Today, a vote that doesn’t direct preferences is invalid, but advocating an informal vote is not a crime.

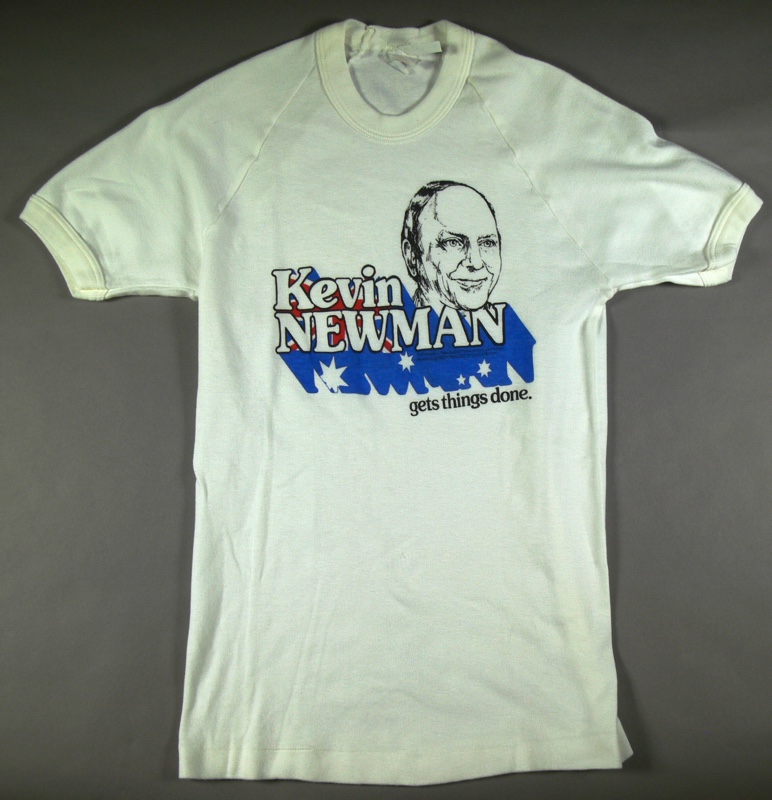

A local member has a lot to do. Not only do they have to be in Parliament during sitting times and cast their vote on laws, they have to be active in their community. A good local member has his or her finger on the pulse of the electorate and can translate that understanding into a strong personal vote. Kevin Newman was well-regarded as a good local member by the people of Bass. Based around Launceston, Bass has been a marginal seat for a lot of its history. In 1975 it was a safe Labor seat held by Lance Barnard, but when he resigned, Liberal Kevin Newman won it with such a landslide it became a safe Liberal seat. Newman’s hard work and campaigning saw him re-elected four times before he retired. This shirt shows his reputation as a man to get things done, something echoed by his son Campbell, Lord Mayor of Brisbane and Premier of Queensland, whose slogan was ‘Can-Do’.

Is there anything that screams ‘1972’ more than a bright orange skivvy that says ‘It’s Time’? The successful 1972 Labor campaign is still remembered as a watershed in Australian politics and history. The slogan graced badges, posters, clothing and more, and its powerful message resonated with the community, particularly younger voters who were not a traditional support base for Labor. It has gone down as one of the most successful political campaigns ever. It is still evoked for some causes, such as the republic. Fortunately for fashion, the orange skivvy has not been as enduring.