Nigel Buchanan: Confessions of an illustrator

- DateMon, 28 Mar 2022

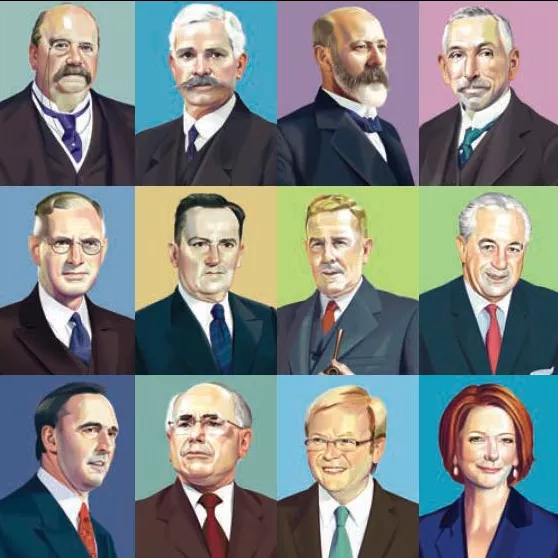

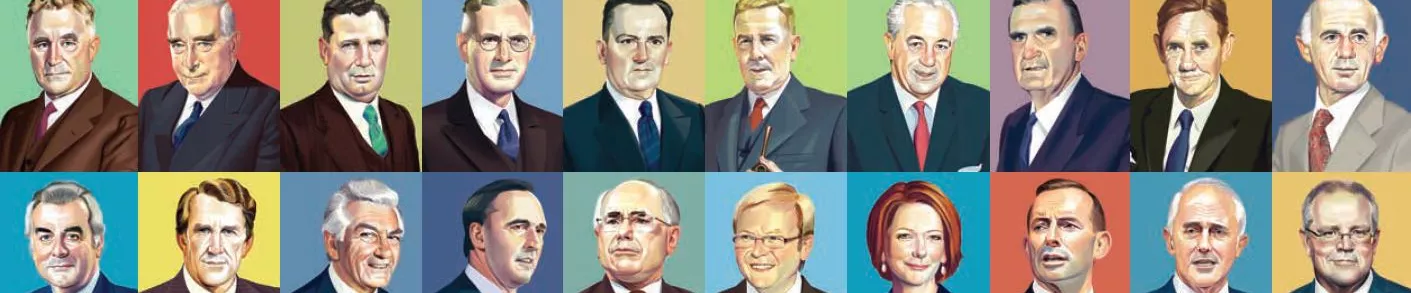

Although it’s been decades since a prime minister held office at Old Parliament House, all 30 of Australia’s former leaders are currently gathered at the Museum of Australian Democracy, just not in the flesh.

Award-winning Queenstown artist Nigel Buchanan has been illustrating famous faces for decades. His playful, graphic portraits have appeared published in major international publications such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and TIME. As part of MoAD’s latest exhibition, Democracy DNA: People, Prime Ministers and the World, Nigel created new portraits of all 30 former prime ministers of Australia. These portraits inject colour and personality into names we may only know from history books.

We caught up with Nigel to discuss broken teeth, tiepins and which former prime minister never seemed to smile.

Tell us about your background. Were portraits always your format of choice?

I studied in New Zealand, then I moved to Australia and lived there for 30 years. I did a lot of conceptual work for various magazines and in the advertising world. There were very few – if any – portraits for the first part of my career.

Later, an art director started a passion project, a soccer magazine called Eight by Eight. He asked me to do some portraits for the first few covers with the magazine winning some awards in New York. This led to a stream of portrait commissions ever since.

Nigel Buchanan's portrait of Andrew Fisher.

What interested you about Democracy DNA and this project?

The scale and the subject matter was really unusual. These people all made a big mark on Australia in their own way, for better or worse.

While illustrating the prime ministers, I realised that I've actually lived in Australia for about a quarter of them. Although there’s been quite a high turnover in the last little while.

The permanence of the exhibition was also really appealing. It's going to stay around for a long time and that's unusual in my work. Usually, magazines have a short lifespan before being tossed in the recycling.

Nigel Buchanan's portrait of Robert Menzies.

Obviously, we only have black and white photos of some of the earlier prime ministers, but your portraits are in full colour. How were you able to determine eye colour and skin tone?

Campbell Rhodes from MoAD did a huge amount of research, he read all sorts of memoirs and notes just to find out what their eye colour was. Campbell found all of the eye colours of the prime ministers, apart from one or two.

Skin colour was really guesswork. [Even in black and white] you could still tell if they were pale skinned or ruddy looking. Or whether they often had a port at night!

Nigel Buchanan's portrait of Stanley Bruce.

Who did you find most difficult to illustrate?

One of the hardest was Fisher. His moustache was so coarse it just looked like bits of string! I'd love to know exactly what he looked like, face to face in real life.

Then there was John Gorton, who had some quite serious war injuries. He’d been patched up during the war, so his scars made up quite a part of the character of his face.

And of course, Joseph Lyons, with curly hair and broken teeth. He's got an awful lot of wrinkles around his eyes and his hair's all over the place. That gave him a lot of personality. I had to make him look slightly less dishevelled than in some of his reference photos. He always seemed to be in a windy day!

What about some of the prime ministers you enjoyed drawing?

The ones I enjoyed weren't necessarily the nicest or my favourite prime ministers. Some of the early ones with their pointy beards were fun. I think beards are considered bad PR these days. Prime ministers are very aware of how they present themselves.

McMahon was quite good to illustrate too because he already looked like he was a caricature. He was fun.

Then McEwen always had a severe look on his face. There were no reference photos of him smiling whatsoever.

Finally, Stanley Bruce wore very dapper suits and a woollen textured tie in all his reference shots. His collars were always neat, and he had always had a tiepin in. He was obviously fashion conscious and made an effort to look right. Whereas some of the others were pretty relaxed about their appearance.

Nigel Buchanan's portrait of Joseph Lyons.

These portraits convey so much personality in a still image. How did you translate your reference photographs into a such vibrant work?

Putting personality into a portrait is about finding the right reference materials. A lot of my reference pictures were formal portraits, but it's usually the candid shots where they reveal more about themselves.

Especially when they’re speaking to crowds, and you can see it in action. Whether they’ve always got their head up, whether they're a bit downtrodden looking, or cheeky, or just don't care. Bob Hawke was always pretty relaxed, whereas Malcolm Fraser was always very stiff.

By getting a broad range of reference shots, you can get a good impression of how they would hold themselves. A lot of the portraits are combinations of different reference shots. I choose the right face, then mix and match, putting references together to give a more accurate whole.

Nigel Buchanan self-portrait.

You can see Nigel’s portraits of all 30 former prime ministers at MoAD’s Democracy DNA exhibition.