The day Robert Menzies retired

- DateWed, 20 Jan 2016

Robert Menzies resigned as prime minister in January 1966, ending the longest period – 16 years – as national leader in the history of Australian democracy.

Beyond this remarkable duration however, Menzies’ significance is evident through two criteria. One is the degree of influence he had on national life whilst prime minister. The other is the enduring impact he had in establishing a political party which actively argued and fought for the ideals, aspirations, interests, fears and needs of the social group Menzies labeled ‘the forgotten people’.

These were the middle classes: men and women without the established wealth and power of big business and the truly rich, nor the organizational power of working classes, whose interests were served by the trade unions and Labor Party. It was this bulk of middle Australia which Menzies identified as the essential dynamic element in Australian life as early as the 1920s. In a political sense, Menzies invented middle Australia. It was his success in establishing a party to represent their interests, the Liberal Party, where his greatest historical significance lies.

Menzies was the central figure in the founding of the Liberal Party in 1944. He’d had previous experience forming a party when he was a key architect behind the creation of the United Australia Party in 1931, the party he was leader of during his first, unsuccessful stint as prime minister. Crucially however, this new party would raise its own funds, and not be directly beholden to big business. Instead the overwhelming priority would be middle Australia. Menzies had identified the ‘forgotten people’ in a 1942 radio broadcast, when he described them as the ‘salary-earners, shopkeepers, skilled artisans, professional men and women, farmers and so on ... the strivers, the planners, the ambitious ones’. He developed policies which spoke directly to the greatest concerns of families establishing themselves in the rapidly growing suburbs of post-war Australia. A sweeping election victory in December 1949 took him and the Liberal Party to power in coalition with the Country Party, and the ideals and aspirations of middle Australia became the dominant focus for this and all subsequent Australian governments.

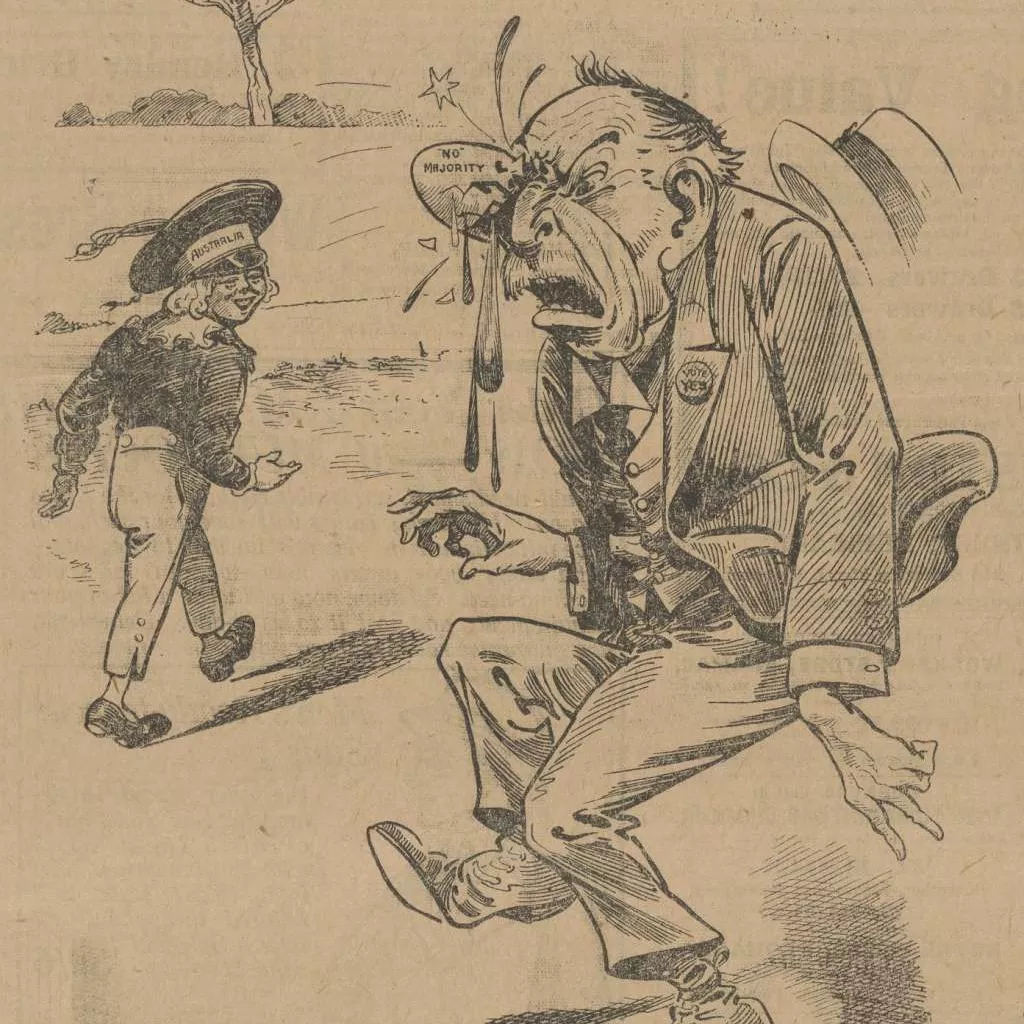

Menzies continued key policies of the previous Chifley Labor government – postwar migration from Europe, government-backing for heavy local manufacturing sector, the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. He also adroitly exploited divisions in the left over communism, winning a series of 1950s elections, although he lost a referendum to outlaw the Communist Party in 1951. The ANZUS treaty, signed with the United States and New Zealand in 1951, probably wouldn’t have been possible under a Labor government.

Neither, arguably, would the 1957 Australian-Japanese Commerce Agreement (only 12 years after they had been enemies in the Second World War, with images of Australian soldiers in POW camps still fresh in the minds of a largely hostile public), which proved so successful that by 1966, the year Menzies retired, Japan overtook Britain as Australia’s leading export market.

Neither again, and this time almost certainly, would the dramatically expanded support which Menzies pushed through for universities. He insisted that all the recommendations of a 1956 inquiry into the tertiary sector be implemented, ensuring both funding and, crucially, autonomy for the institutions which a new generation passed through in the 1960s and early 1970s.

The irony here is that the majority of these university students, largely the children of the middle class parents who Menzies had always championed, actively (and this is not too strong a word) reviled him. They saw him as an anachronism, ‘the last of the Edwardians’, scion of an outmoded set of attitudes, behaviour and practices. More specifically, it was Menzies who had reintroduced compulsory military service in November 1964, and sent Australia’s first combat battalion to fight in the Vietnam War in 1965. It was the prime ministers who came after him who radically expanded the numbers sent to fight an eventually highly unpopular war, including conscripts, but it was under Menzies that the direction was clearly set. Many of the younger, tertiary educated generation would never forgive him for that.

In the final analysis, then, a prime minister both loathed and loved. But a prime minister who shaped the trajectory of an entire post-war era, and one who formed a political party according to the ideals and interests of the middling ranks, or mainstream, of ordinary Australian men and women. Not simply a political colossus, more successful than any other person in the history of Australian democracy, but one of real, enduring historical significance.