What is a redistribution?

- DateMon, 14 May 2018

At least once every seven years, the Australian Electoral Commission has to reassess and redraw the boundaries of a state's federal House of Representatives seats.

Sometimes these changes are fairly minor and sometimes they can be substantial. But how does this process work? And why do they do it at all?

Constitutional basis

The key principle behind redistributions is called 'one vote, one value'. This means that the number of voters in all seats is about the same. In the past, some seats had drastically smaller numbers of voters than others, usually outside the major cities. This meant that some rural members had to earn fewer votes than their urban counterparts, and rural seats had an influence out of proportion to their size.

The basis for electoral redistributions is Section 24 of the Constitution. Each state is entitled to a minimum of five members, regardless of its size. Beyond that, each state's representation is based on its population, with larger states like New South Wales and Victoria having more members than the smaller states. As populations grow in different areas at different rates, states gain or lose seats every so often. For example, at the 2018 redistribution, South Australia lost one seat, while the ACT and Victoria each gained one.

The timing

Redistributions are governed by federal law. The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 says a redistribution is due when a state's population grows or shrinks enough to change its allocation of seats, if one particular seat gets too large, or seven years since the last one. Seats in every state and territory are regularly redistributed, usually due to elapsed time. There are exceptions – Queensland's population boom in the early 2000s meant it had one extra seat at three elections in a row.

Change of boundaries

Redistributing seats is extremely complicated, and the process begins long before it is due. The boundaries of each electorate are redrawn to make sure the size of each one stays equal – this can involve minor tweaks like removing some streets or suburbs, or massive changes including abolishing entire seats or adding extra ones.

Redistributions only take effect at federal elections, so if a sitting member resigns and causes a by-election, the old boundaries will still be used until the full election takes place.

Change of names

Unless you happen to live in one of the areas affected by a redistribution, the most likely effect for you would be a name change. Names of the seats are decided by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), but public consultations take place to ensure community support. There are a few guidelines they try to follow. The usual practice is to name them after prominent Australians, and every deceased prime minister with the exception of Joseph Cook has one named for them. Cook misses out because his namesake, Captain James Cook, already had one. Malcolm Fraser will be honoured with a new seat in Victoria from 2019; the previous seat of Fraser in the ACT was renamed to Fenner in 2016 in order to free up the name.

Another policy is to try to keep the original 65 seat names that were used at the first election in 1901. These names include Eden-Monaro, Melbourne, Richmond and Wide Bay.

In recent years, prominent women and prominent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders have been priorities for the AEC when assigning names. Currently only six seats are named for Indigenous people and only sixteen for women, so the AEC has begun to address that lack of diversity.

Change of member?

What does a Member of Parliament do if their seat is removed? Changes to the boundaries can affect the result of an election. The results from each polling booth are known, so when boundaries are changed, the last election is recounted with the new boundaries. This doesn't change the result, but it could mean a member's margin of victory is massively reduced or increased. A seat that was won by a Liberal candidate could shift to become a Labor seat, albeit one with a Liberal member until the election. That member then chooses whether to recontest the new seat, or try to find another one. Parties sometimes make deals among their MPs, shuffling them around different seats when one is abolished.

Case study: Denison/Clark

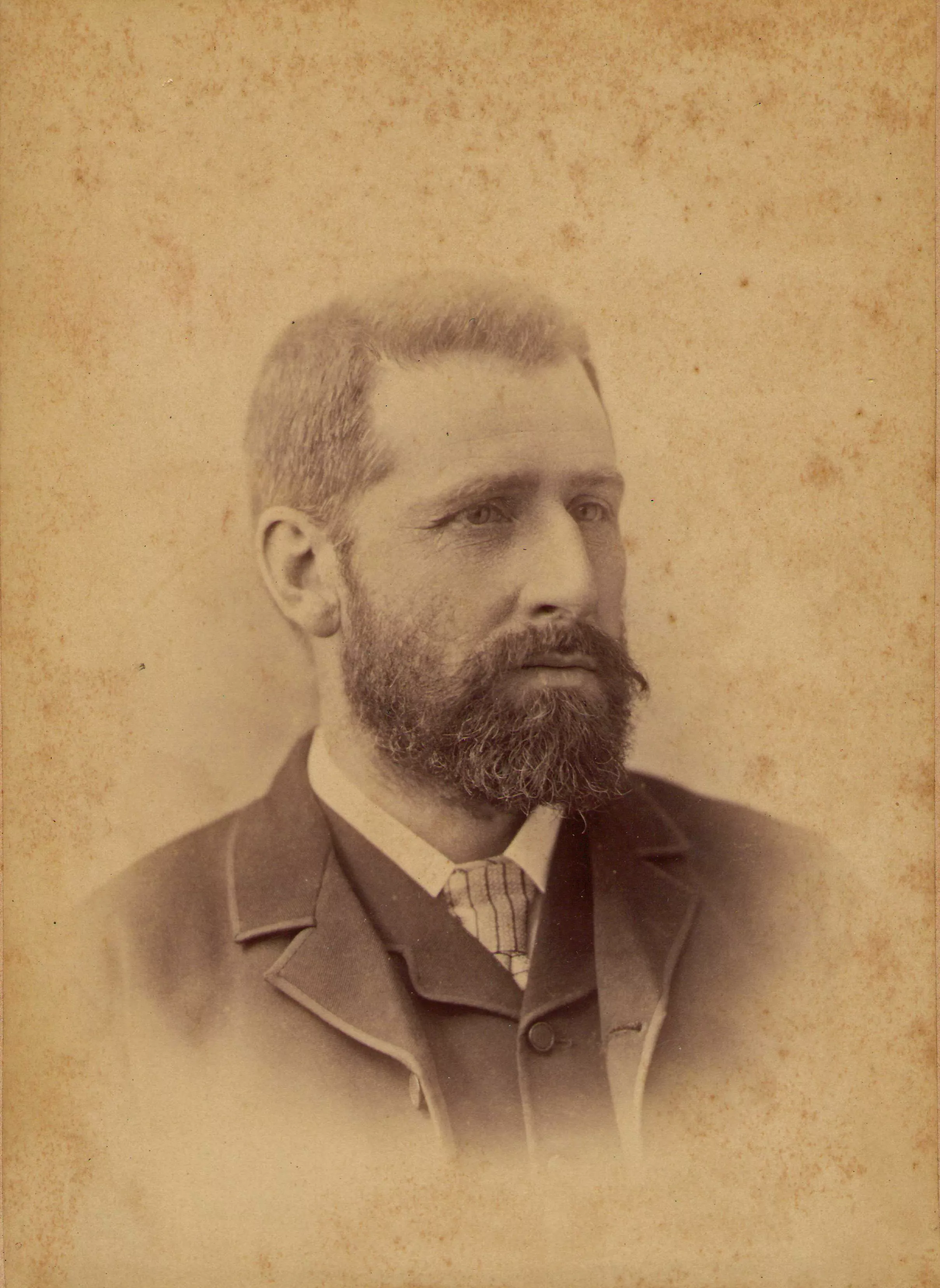

The Tasmanian Division of Denison was affected by a redistribution in 2017. Tasmania only has five seats, and a relatively stable population, so the boundaries have hardly changed at all. But during the current redistribution process, a public submission to the committee has suggested renaming Denison to Clark.

The name 'Denison' comes from Sir William Denison, a 19th century colonial governor of the colony. The proposed change honours Andrew Inglis Clark, a Tasmanian who drafted a number of significant clauses in the Constitution and helped create the Hare-Clark electoral system. Because of the importance of Clark, the committee in charge of the redistribution has agreed to change the seat of Denison to Clark. The incumbent member, Andrew Wilkie, will remain Member for Denison until the next election.

Portrait of Andrew Inglis Clark.

Photograph National Library of Australia

Case study: 'Bean'

The Australian Capital Territory has had two members since 1974, with a brief period from 1996-98 when it had three. In 2019, it gained a third, as its population became high enough to warrant a third seat according to the rules.

Turning two seats into three essentially meant completely redrawing the map. About a third of Canberra's population is in each seat, with the new seat consisting of the southern suburbs, with the middle seat, Canberra, adjusted northwards to make up the difference.

The Australian Electoral Commission proposed to call the new seat 'Bean' after Charles Bean, the First World War historian and one of the founders of the Australian War Memorial.