Only human – disability in Australian politics (part 1: human leaders)

- DateFri, 02 Dec 2016

Every now and then, a news article laments the lack of people with visible disability in Australian politics.

It is a case well made – looking across Federal political history few of our leaders have openly identified as disabled people, or talked about disability as a policy issue. Most books on Australian politics don’t even mention disability until recent times when the campaign for a National Disability Insurance Scheme propelled it onto the front pages. Yet according to most estimates around 1 in 5 Australians have a disability. Have we been run by a group of super humans since the colonies federated in 1901?

If you look in the right places, disability has been part of the political story of Australia and our leaders since the beginning. The nation’s highest office has taken a toll on its leaders and leaders have come to that office with disabilities, most notably from war.

The line between disability, ageing and health issues is a blurred one, but one thing we can say is that if you didn’t enter high office with a disability you often left with one.

The nation’s highest office has often exacted a toll on leaders and so it was with the first Prime Minister Edmund Barton.

Barton is perhaps not well served by descriptions of him which draw heavily on the writings of his journalist colleague and successor, Alfred Deakin who wrote that:

‘In later years his figure became too corpulent to be graceful so that his Apollo-like brow and brilliant capacities were to some extent chained earth by his love of good living. At no time and in no sense intemperate, his genial, affectionate nature made him so companionable that he spent many hours in his club chair which could have been more profitably spent in his chambers or in his study.’

Whatever the cause, the office took its toll and Barton collapsed in his room in Parliament House in August 1903 following a bout of ill health after travelling to England. He resigned on 24 September 1903 to become a Judge of the High Court of Australia.

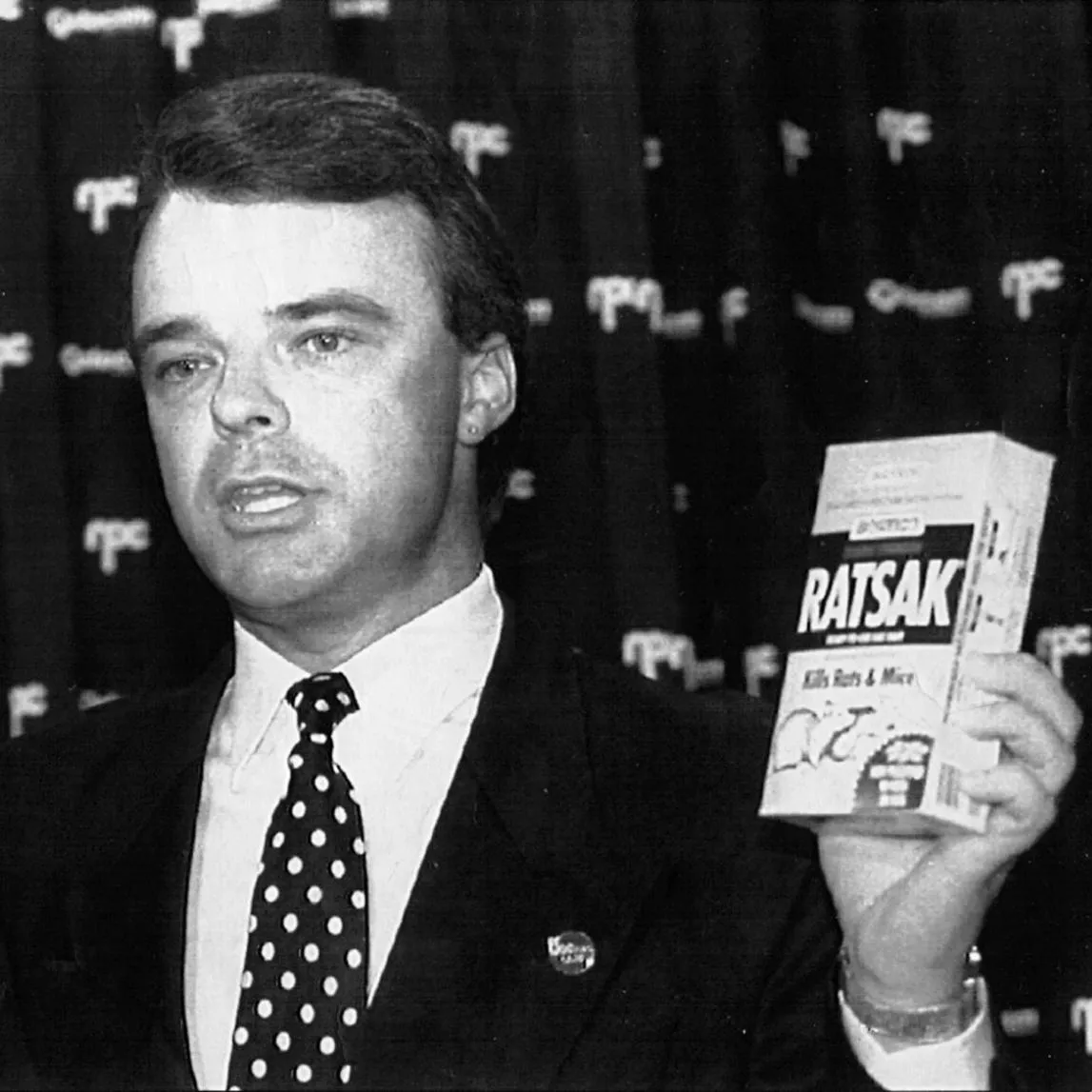

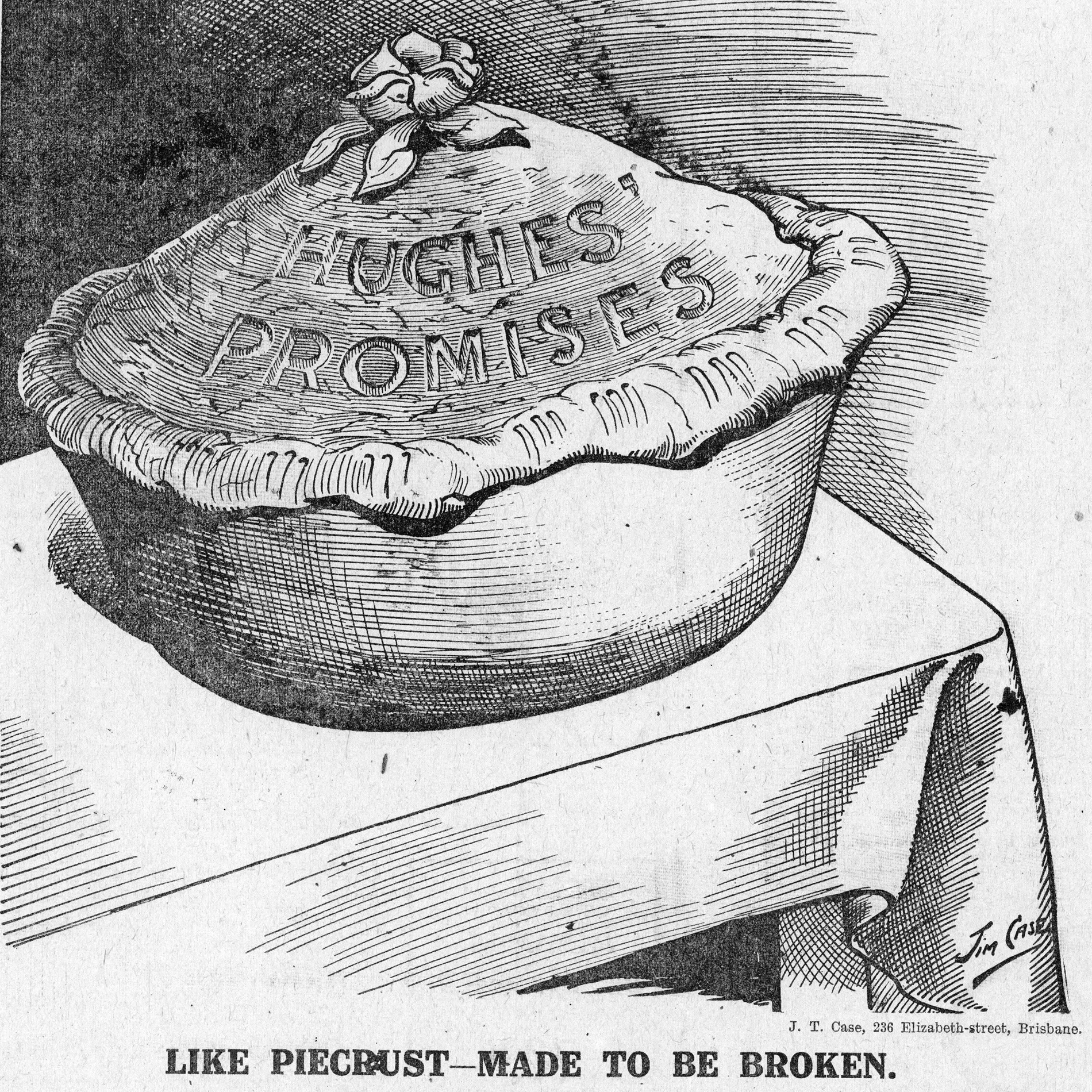

Jump forward a decade and the chronic health conditions of another Prime Minister may have played a part in the defeat of the 1917 conscription referendum. While hardly a supporter of Hughes, there is a tinge of admiration in Donald Horne’s description of him as a dogged fighter whose chronic health conditions formed a key part of his political character:

‘… from 1916 to 1922, usually exhausted, often sick, he was a gambler, enjoying quick spurts of success, but often living in terror of being caught out …’

When Parliament met after the failure of the 2nd referendum on 11 April 1918, Horne described him as ‘too sick to attend Parliament, his speech giving the Government’s plans is read out for him and is seen by the newspapers as disappointing.’

The story of war was the public face of disability in politics for decades with Prime Ministers up until the 1970s more likely than not to have seen war service.

Stanley Bruce – the twelfth Prime Minister, enlisted in the British army – fought at Gallipoli in 1915 as a captain, and was awarded the Military Cross and Croix de Guerre. After being wounded twice, he was invalided back to London when his knee was shattered by a bullet. He spent the next two years on crutches.

On the eve of the Second World War another leader would find his health becoming ‘a source of concern to party powerbrokers’ in the United Australia Party. Eight years of office took their toll on Joe Lyons and he became the first Prime Minister to die in office on 7 April 1939.

Office took the ultimate toll on wartime Prime Minister John Curtin who became the second Prime Minister to die in office on 5 July 1945. After a brief interregnum he would be followed by Ben Chifley. Chifley also felt the strain of office suffering a series of heart attacks. The final, fatal one would occur to the now Opposition leader on 13 June 1951.

Menzies in his 16-year-long run as Prime Minister seems to have had robust health but might be forgiven for retiring on the basis that ‘In short, I am tired; my pace has slowed down; I could not properly continue in office for very much longer and at the same time do justice to the growing problems of the nation,’ at the age of 71.

Australia also had a Prime Minister with what would be now be recognised as a significant appearance difference.

John Gorton, elected following the disappearance of Harold Holt, had been a fighter pilot in World War Two and his war story reads like a Biggles novel. His face was slammed into the instrument panel of his bullet ridden Hurricane in landing on the Singapore aerodrome as an RAAF dogfight raged ahead. His entire face was rebuilt. Gorton was still swathed in bandages when the ship on which he was being evacuated from Singapore was torpedoed. Gorton spent 24 hours on a raft in the waters north of Batavia before being picked up by a warship. Back on active duty later in the war he again crash-landed on an island in the Timor sea and lived for days on turtle eggs and fish before being rescued.

Another veteran to have served in the Parliament with a disability was Graham Edwards a Vietnam veteran who served in the Australian Parliament as Labor member for Cowan from 1998 to 2007. On 12 May 1970, he was severely injured, losing both legs. Edwards is the only member of the Federal Parliament to serve using a wheelchair for mobility.

At least three Prime Ministers have had significant hearing loss. Billy Hughes operated an ‘accousticon’ or hearing machine, with contemporaries alleging that when he wished not to hear, he would just turn this off. He also had a telephone made with an amplifier made by the Research Laboratories of Melbourne. Sir William McMahon who was Prime Minister in the early 1970s and John Howard (1996–2007) both used aids and had significant hearing loss. Howard went on to be an advocate on some deafness issues after his time in office.

Political spouses have stories to tell. There probably isn’t an Australian alive from the 1980s who doesn’t recall Jan Murray, the Cabinet Minister’s wife who rocked the nation with a cheeky interview on the 60 Minutes program revealing she claimed her conjugal rights on a desk once used by John Curtin in her husband John Browns office in the early 1980s.

What you mightn’t know is that Jan Murray was also deaf, got through her early school and university years by lip reading and writes extensively in her biography on the poor accommodations offered to deaf people in education:

‘Looking back, the odd thing is that once having identified my disability, not a damn thing seems to have been done in the course of my education to accommodate it. I travelled up through my school years carrying form, but no report on my impairment … I would be a thirty something university student in third year politics at Macquarie University before someone thought to offer me a learning aid to compensate me for my hearing loss. I was assigned a person to sit alongside me during lectures and tutorials to interpret for me should I miss words and exchanges. I had difficulty taking notes while a lecturer was speaking. I could do one or the other – wrote or listen but my need to read lips made it impossible to do both while simultaneously. Hearing aids, of which I gathered plenty over the years, have never been the answer.’

In an engaging biography released in 2010, Jan talks about her son’s spinal injury and devotes several chapters to her experiences with bipolar disorder which included being admitted as an involuntary patient under the Mental Health Act and her long journey through the care and treatment system battling mania, depression and anxiety.

The task of leading Australia continued to exact a toll on leaders in modern times – physical and mental.

The affable Liberal Minister, Sir Jim Killen, recalling his own brush with a physical and nervous breakdown, wrote this of Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser in the early 1980s:

‘If I was starting to feel better, then I was getting increasingly concerned with the Prime Minister’s appearance. The more I saw of him the more I was convinced that a stress similar to the one which had ravaged me was now attacking him. Mannerisms are not easily disguised. Malcolm Fraser had always been a tense person, but his tension was more manifest and he became much more easily agitated. The skin on his face appeared to be familiar to the skin I had known on my hands for many months …’

Sometimes disability can be a brush with fate away as Fraser’s successor Bob Hawke discovered when glass fragments had to be removed from his eye following an incident during a Cricket match between the Prime Ministers staff and the press gallery. Hawke governed the nation with an eyepatch for days.

Politics is about perceptions and disability can be too. It is no accident that the Disability Discrimination Act passed in 1992 during the Keating Government talks about discrimination arising from real or perceived disability.

There is perhaps no better illustration of the power of perceptions than in the turn of Opposition Leaders during the Howard Government.

Both Mark Latham and Kim Beazley, rivals at times, ended their terms as Opposition leader on the spark of concerns about their health.

Beazley’s last stint as Opposition leader was ended after a minor verbal fumble where he confused Rove McManus with Karl Rove, reportedly casting doubts over his recovery from Schaltenbrand's syndrome, in which cerebro-spinal fluid leaks from around the brain. Mark Latham’s stint ended amid a bout of pancreatitis which saw him criticised for not issuing a statement following the tsunami in January 2005.

Yet, in a pointed sign that imputation is not reality, both continued in public roles for years afterwards – Beazley as United States Ambassador and Latham as a public commentator.

As a final twist, Kevin Rudd, who succeeded both men and ended Labor’s run in Opposition, talked openly about his health and transplanted aortic valve, yet will be possibly best remembered for setting a 24/7 pace that played a part in his ousting by exhausted Cabinet colleagues in 2010.