Besties (or not) from the West: PMs and Presidents

- DateFri, 20 Jan 2017

January 20 is Inauguration Day, when a newly elected President of the United States takes office.

Whichever person occupies the Oval Office affects Australia in different ways, not the least of which is the nature of the relationship between the President and Australia’s Prime Minister. The personal rapport, or lack thereof, can have a real effect on foreign policy.

As Donald Trump takes office as America’s 45th President, here are some meetings between the two nations’ leaders that you may not know about, and that had a real effect on Australia’s place in the world.

At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, Wilson and Hughes met once more. Billy Hughes was even more brash and blunt as he had been the year before in Washington, and Wilson even more unimpressed. Image: State Library of Queensland

When Billy Hughes visited the White House in May 1918, he hoped to dazzle the President with his charm, and argue Australia’s case for administration of New Guinea. Unfortunately for the loquacious Hughes, his opposite number did not respond to his winning personality. In a meeting that lasted less than half an hour, Hughes went on a long diatribe, only for Wilson to reply with stony silence. Whether it was because he could get a word in edgeways is unclear, but it was also Wilson’s habit of simply not replying when he was annoyed what someone said. Hughes, exasperated, finally gave up, and left the White House with no progress made and feeling somewhat relieved. It was the first meeting between an American President and an Australian Prime Minister and probably the least effective.

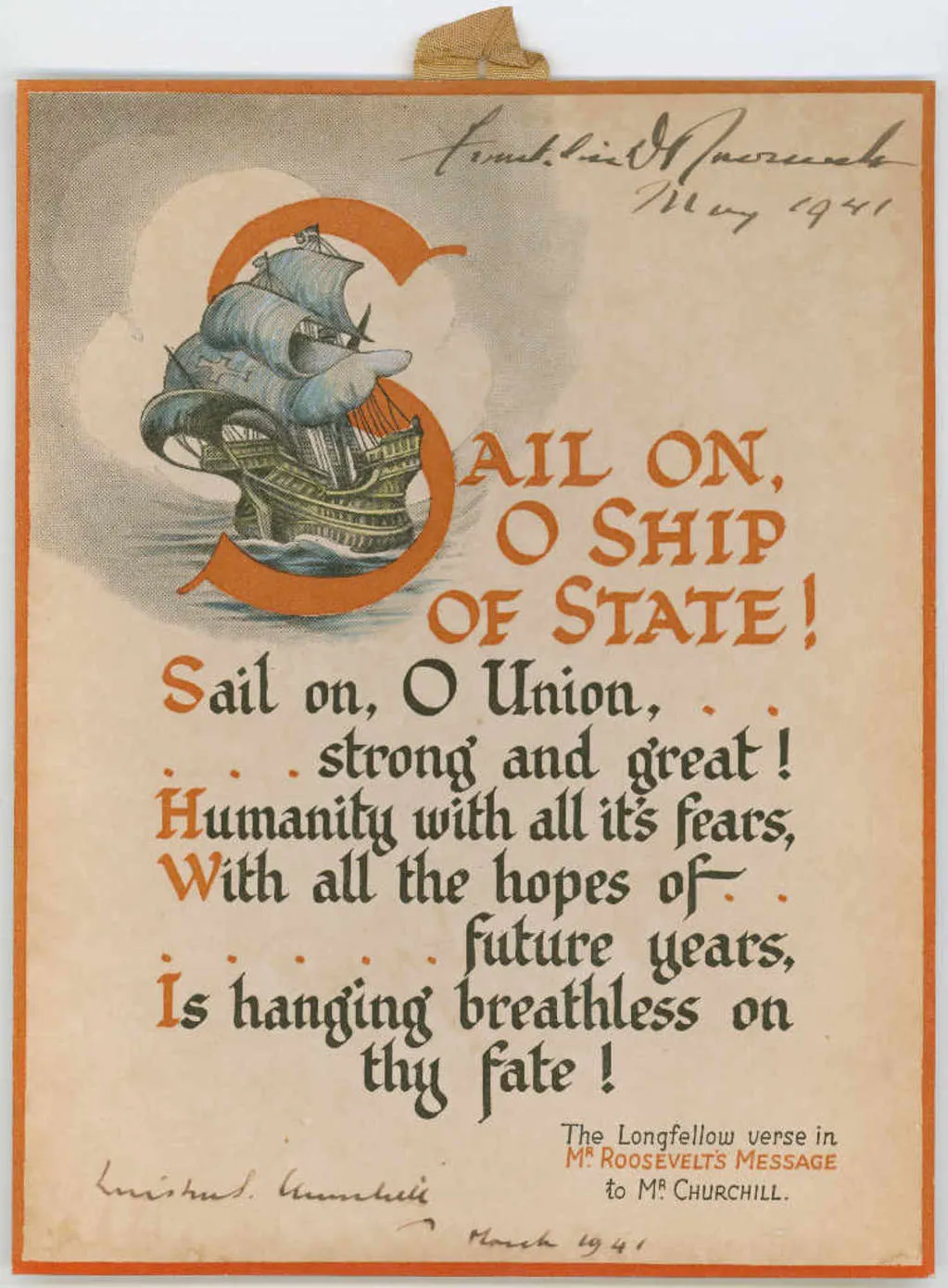

O Ship of State: Franklin Roosevelt & Robert Menzies

In May 1941, Prime Minister Robert Menzies stopped in Washington to meet with President Franklin D Roosevelt. The president was bed-ridden with gastritis. Menzies, in his diary, reflected the president looked ‘older and more tired’. Nevertheless, the two met for an hour, discussing the war and American public opinion on intervention. Menzies’ diary reveals Roosevelt told him he was jealous of all the world’s media attention on Churchill, and Menzies advised him to meet with his British counterpart.

Three months later, Churchill and Roosevelt met in Newfoundland and signed the Atlantic Charter, a document which all but ensured American entry into the war.

Earlier, in London, Churchill had presented Menzies with a gift – a printed copy of a verse by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Roosevelt had scribbled a copy of that verse and sent it to Churchill earlier that year as a sign of support. Menzies had Roosevelt sign it at his meeting with the President. Now in the Museum’s collection, it was one of Menzies’ most treasured possessions and is now one of ours.

All the Way: Lyndon Johnson & Harold Holt

One of the most celebrated relationships between a Prime Minister and President is the friendship between Harold Holt and Lyndon Johnson. En route to England in July 1966, Holt stopped in Washington for a meeting with the larger-than-life Texan. The charismatic Johnson clearly won over the affable PM with his famous ‘Johnson treatment’. ‘Wait until you meet him,’ Holt told his wife Zara, ‘I’ve never met a nicer, warmer, straighter or better fellow in my life.’ The invitation had only been for a small, informal luncheon, but Holt discovered to his surprise that Johnson gave him an honour guard and a 19-gun salute. Both men were extremely hard workers, and spent their time deep in conversation with advisers and each other on the Vietnam War. In his speech on the White House lawn, Holt famously told the world that he, and Australia, would be 'All the Way with LBJ.'

A month later, Johnson became the first sitting President to visit Australia. He and Holt would meet again; in 1967, Holt stayed at Camp David, where he and the President spent the day by the pool with telephones. It would be their final meeting; on 19 December, Holt drowned off Cheviot Beach near Portsea, Victoria. A devastated Johnson flew to Melbourne for the memorial service of his friend.

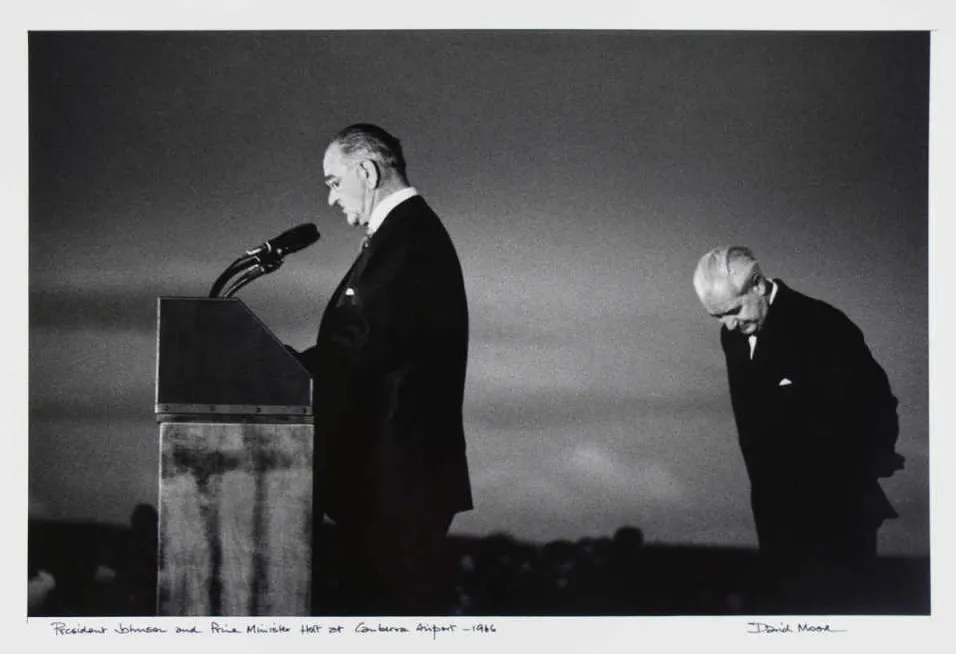

This photo of Johnson and Holt was taken by David Moore at Canberra Airport when the President visited Australia. Holt simply happened to be looking down when the photo was taken, but his pose was interpreted as deferential or reverential towards President Johnson. Image: David Moore, Museum of Australian Democracy Collection

Elephant in the Room: Richard Nixon & Gough Whitlam

Gough Whitlam’s government and Richard Nixon’s administration had a frosty relationship. In December 1972, days after Whitlam came to office, an intensified bombing campaign by the US against North Vietnam saw international condemnation, including from Whitlam himself. Some of Whitlam’s ministers had described the Nixon administration as ‘maniacs’.

When they met in Washington in July 1973, the two men could find little common ground and little to say. During the photo opportunity in the Oval Office both men ‘mumbled with massive dedication to ceremonial appearance’. At the meeting itself Nixon toyed with Whitlam, suggesting western powers had no strategic direction. Whitlam buttered Nixon up with talk of the power of the United States and the strength of its alliance with Australia. Then he told Nixon not to be discouraged by politics (by which he meant Watergate). Nixon didn’t take the bait, and focused on his perception that Australia might wander from the foreign policy it had pursued for decades. Neither mentioned the current state of relations, Vietnam, or their obvious distaste.

Throughout the rest of Nixon’s term, he would react with anger or retaliation at Whitlam’s foreign policy, including a review of intelligence sharing when Whitlam announced a review into whether to allow U.S. bases on Australian soil. By the end of 1975, both Nixon and Whitlam were out of office after dramatic political upheaval.

Ron and Bob: Ronald Reagan & Bob Hawke

When he became Prime Minister in March 1983, Bob Hawke began preparing for his first overseas visit. The original plan was to visit Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, but then Hawke received a surprising letter. The letter was from Ronald Reagan, inviting him to Washington, and expressing a desire to work closely with him. Hawke immediately decided to include the United States on his itinerary.

The two charismatic leaders found much common ground, despite their ideological differences. 'Instantly,' Hawke later wrote, 'President and Prime Minister were Ron and Bob.' Hawke described Reagan as a warm, friendly man, and described how even Reagan’s political enemies liked him on a personal level. Hawke was blown away by the President’s easy, conversational tone, and his willingness to listen to his advisers.

Hawke and Reagan met five more times in Washington, and to this day Hawke describes the 40th President as a good friend. But it wasn’t all smiles; Hawke also recalls discussions over the U.S. ‘Star Wars’ missile defence program. Reagan turned his charm up to maximum and plied Hawke with lunch, but to no avail. Hawke refused to take part in the program. Friends could disagree and remain friends.

Man of Steel: George W Bush & John Howard

Though they didn’t meet face to face, George W Bush spoke to John Howard over the phone in 2000, after becoming the Republican nominee for the presidency. In that conversation, Bush took care to express condolences for Sir Donald Bradman, one of Howard’s heroes, who had died the previous day. When they finally met in September, the day before the September 11 attacks, they got on well. Howard describes Bush in his memoirs as a ‘highly intelligent man with a well-organised mind,’ with a ‘tendency to humorous self-deprecation’.

In the aftermath of the attacks, the United States and some of its allies, notably Britain and Australia, committed military force to combat the Taliban in Afghanistan, and then the regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Howard’s controversial decision to participate, particularly in Iraq, drew much media attention to his personal relationship with the American president. Bush called Howard a ‘man of steel’, referencing his view of Howard as a tough but devoted ally.

Howard saw his friendship with Bush as symbolic of the friendship between both nations. In this, and indeed in the commitment of troops to a war overseas, there are obvious parallels to the Holt/Johnson friendship of years before. Like Holt, Howard invited the President to visit Australia. During Bush’s visit there were many protests, as there had been during Johnson’s, and to this day the close relationship remains a controversial one.