The same, but different: the UK election compared to Australia

- DateTue, 06 Jun 2017

With many ex-pat Australians living and working in Britain, and millions of Australians having British ancestors, political developments in the United Kingdom are closely followed by Australians.

There are many similarities between British and Australian democracy, but also some major differences. We thought we would look at some of the key similarities and differences between the two.

A common crown

Britain and Australia are constitutional monarchies, with power vested in the monarch or, in Australia, their representative, the governor-general. Both nations have a form of government based on delegating the power of the Crown to the elected government. Neither the monarch nor the governor-general are involved in politics or make partisan statements, although there have been exceptions to this, particularly in Australia. While the governor-general is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the Australian government, the Queen, or King, becomes monarch through inheritance.

Lords and Senators

In Australia the Senate (which was modelled on the American Senate) is elected, with each Senator chosen by the voters of their state or territory. The upper house in Britain, the House of Lords, is not elected at all, except in certain circumstances.

Before 1999, the House of Lords consisted of every hereditary peer (barons, earls, dukes and so on), plus hundreds of 'life peers', appointed by the government for their lifetime. Reforms have meant only 92 hereditary peers are entitled to a seat (these peers are chosen by all hereditary peers, the only elections for the Lords), as well as the life peers.

Some people believe the House of Lords is undemocratic, an anachronistic throwback to the days of feudalism and serfdom. Another school of thought believes the Lords provides a barrier against excessive, radical policies.

The House of Lords can no longer reject government legislation, except under very specific circumstances. It can, however, delay bills and provide a check on the power of the House of Commons. The Australian Senate can reject any piece of government legislation.

Westminster

The Westminster system is so-called because the British parliament meets at the Palace of Westminster, and Britain exported its parliamentary form of government to its colonies. Both the UK and Australia elect a parliament, which makes laws, and government is formed by the party or coalition with a majority of seats in the lower house (Australia: House of Representatives, UK: House of Commons). The British parliament has Question Time (called Question Period or Prime Minister's Questions), a Speaker, red and green upholstery, and many other elements that Australians would recognise.

First past the post

In Australia, a voter ranks all the candidates according to their preference. Lower-polling candidates are eliminated from the count, the preferences recalculated, until a winner emerges with a majority over their last opponent. In Britain, the system is much simpler – whoever gets the most votes wins the seat, even if they don't have a majority of the votes cast. Some people in Britain think this 'first past the post' system is undemocratic and unrepresentative. A referendum on changing to a kind of preferential system was defeated in 2011.

Voting day

Australian elections are always held on a Saturday. This was a deliberate decision on the part of lawmakers, who wanted to make sure most people didn't have to work on election day, and that the day was convenient for as many as possible. In Britain, since 1918 almost every election has been held on a Thursday. This was designed to limit the influence of brewers and publicans (who favoured the conservatives) over their patrons (who would go for a drink after being paid on Fridays), and from the influence of preachers on Sundays.

Constitutions

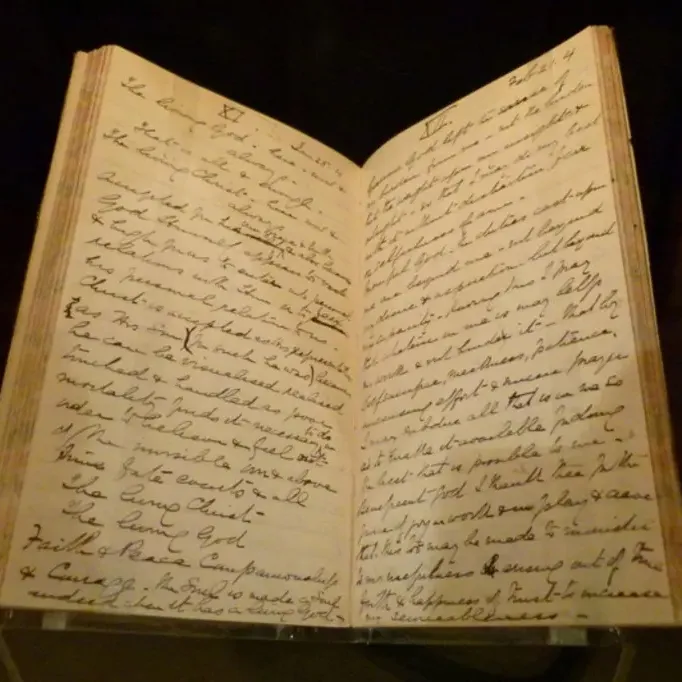

Britain, unlike Australia, does not have a written constitution. Almost all of the machinery of government in the United Kingdom is based on convention or legislation. There are many restrictions placed on the powers of the Crown, the Parliament, the Cabinet and so on, but none of them are codified in any single place. This is because Britain's system of government evolved over hundreds of years, from a feudal monarchy to a constitutional, democratic state. Australia does have a constitution, which is itself an Act of the British Parliament. Australia's Constitution is the country's highest law and can only be changed through a national referendum. Referendums in the UK are consultative, and usually on matters of major importance when the government wants a mandate, such as the Brexit vote in 2016.

Prime ministers

Both Australia and Britain have a prime minister, who is the national leader. Because of the Westminster system, they are chosen the same way: by being leader of the party that controls the lower house. Therefore while they are democratically accountable, they are not, strictly-speaking, elected by the voters.

In both countries the prime minister is considered 'first among equals'. Media focus is usually on the PM above all else, and despite the theoretical or actual limits to their power, both countries' prime ministers are considered to be the main source of authority, by the media if not the population at large.

Term length

In Australia, the House of Representatives serves a maximum of three years, and the Senate (except for Territory senators) a fixed six-year term beginning on July 1. The House of Commons is elected for a term of five years. In both countries, the House can be dissolved early, but the process is simpler in Australia. The Australian prime minister only has to advise the Crown (through the governor-general) to dissolve parliament.

In Britain, this used to be the case as well, but reforms in 2011 meant the term of each new parliament is fixed at five years. The exception is that a two-thirds majority of the House of Commons can vote to dissolve early. This is why in 2017 Prime Minister Theresa May was able to call a new election only two years after the last one. Under normal circumstances, she would have had to wait until 2020.