Why do we have elections anyway?

- DateWed, 06 Apr 2022

For some, elections might seem a boring chore, but plenty of others think they’re a vital part of our society, and important since we live in a democracy.

You might be an enthusiastic supporter of one side or another, or totally apathetic, but if you are an Australian citizen, you not only have the right but the requirement to vote in free, democratic elections. But why?

Democracy 101

Democracy is a word that comes from two Greek words – 'demos', meaning people, and 'kratos', meaning power.

Democracy = people power.

There's more to living in a democracy than just elections, but could you have a democracy without them? Maybe – political science is full of debate about that. But we take it as read in democratic societies that elections are part of the system, and that the government is chosen by the people.

In English-speaking democracies at least, we owe our tradition of elected government to centuries of history. If you've ever watched Game of Thrones you'll recognise a lot of what we're about to tell you, because the show and books are based on real historical themes.

You win or you die

Most societies from the very beginning of human civilisation were ruled by a (usually male) monarch, whose word was law. Most of these monarchies were based on the idea of divine right – the theory was that by being born, the monarch had the endorsement of divine powers, and thus opposing them was opposing the will of the cosmos.

Of course, some people did oppose the monarch, and found increasingly sophisticated ways to do it. In 1215, when a group of landowning lords in England waged a war against King John and his whims, mostly around taxes they felt were unfair.

Simon says

In time, it became normal for the monarch to seek the advice and approval of nobility. When the nobility again rebelled against John's son, Henry III, the matter was settled by handing some of the king’s power to a council of nobles.

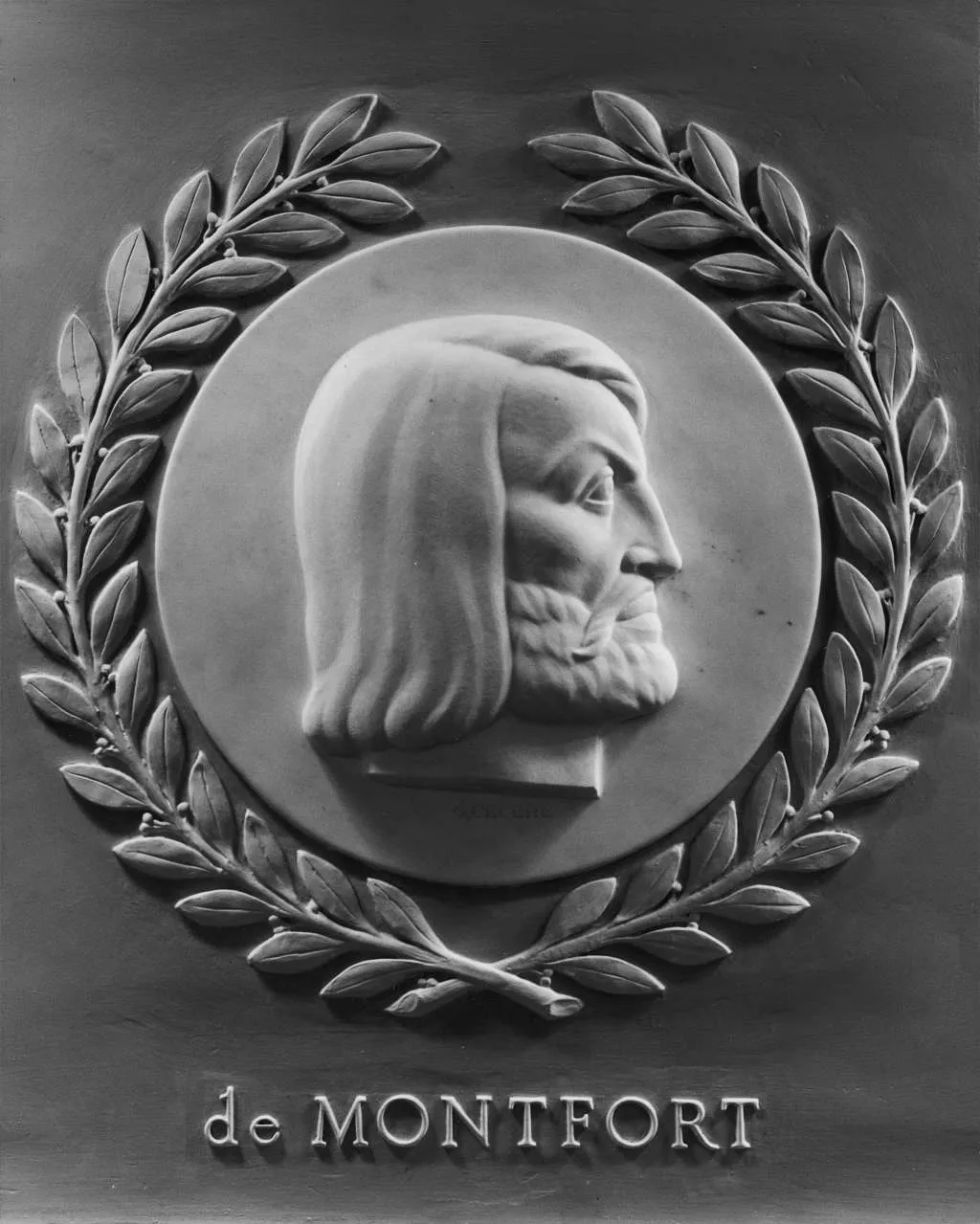

One of the leaders of the rebellion, Simon de Montfort, was effectively now the ruler of England. To help him rule he summoned a council not just of nobility and religious leaders, but of knights and free citizens as well.

By the end of the 13th century it was tradition that citizens across England had representation in Parliament, although they were usually chosen by an elite few rather than by the people.

After ruling England for about a year, Simon de Montfort himself was overthrown by King Henry's forces, and killed at the Battle of Evesham. One of the soldiers that killed him later died after Simon's niece pushed him into the river.

King John is known for having signed Magna Carta, limiting his own power. His reputation as a weak and tyrannical king has become quite literally the stuff of legend, as he is usually the villain in tellings of Robin Hood. National Portrait Gallery (United Kingdom)

Oliver Cromwell's statue still stands outside the British Parliament today, mixed legacy notwithstanding. Karen Roe via Flickr/Creative Commons

Simon de Montfort was one of the most important people of his age, and ruled England in the king's name. Of course, he took this power by the sword and not democratic means. Nonetheless his reforms were so long-lasting, a bas-relief of him is installed in the US House of Representatives. Architect of the Capitol/Creative Commons

Oliver's army

Let's flash forward a few hundred years. For centuries since Magna Carta, kings had been in a balancing act, trying to keep Parliament on their side but still exercising the real power. It was this clash of ideals that led to the English Civil War in the mid 1600s. Charles I went up against his parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell, and lost. He didn’t just lose the war – he lost the kingdom and, ultimately, his head. Cromwell ruled England as a dictator, and he was king in every way except name.

So even at this point, the idea that the ruler of the country was the king, not the parliament, was still very much in people's minds. The monarchy was eventually restored, but it wasn't until the 1700s, with revolutions in the United States and France, that the idea that you could have a government without a monarch at all really caught on in England.

That's revolting

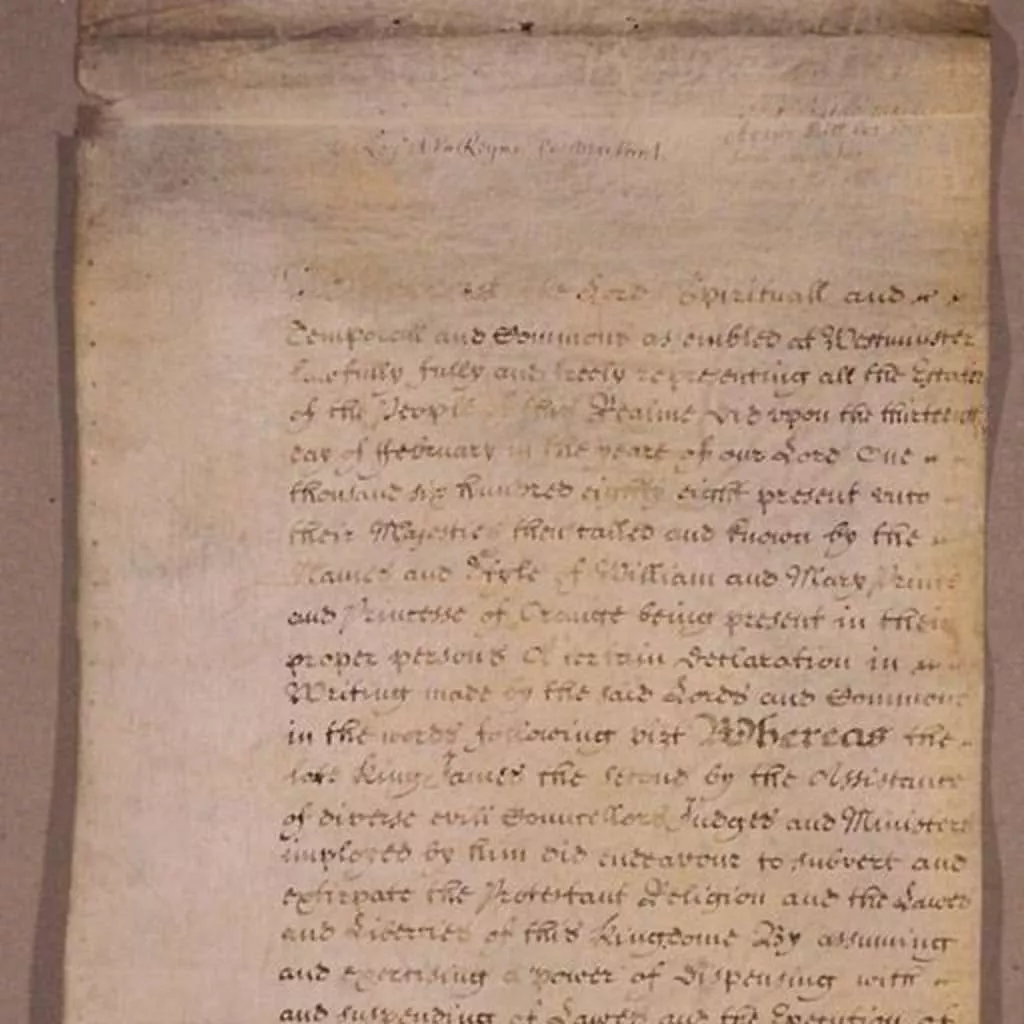

The overthrow of Charles I didn't put an end to the struggle. Charles I's son, James II, was a Catholic, and he made it part of his regime to vigorously pursue a Catholic agenda. He named Catholics to high office, removed restrictions on Catholics, and even made Anglican priests read out his pro-Pope declarations. As he was head of the Protestant Church of England, this was an enormous conflict of interest. More than that, James had faced a number of rebellions and he shored up his military support against Parliament's will.

Nobles and parliamentarians feared another civil war. They agreed that something had to be done, and they invited the Protestant William, Duke of Orange, a Dutch noble married to James' daughter Mary, to invade England and take over. Mary was a Protestant and they originally only planned for her to be queen, but William, once he had invaded and taken charge, insisted on being made king in his own right. Parliament agreed to that, and passed laws setting down the way things to be from now on. The English Bill of Rights set in stone the idea that the British government was not run by the king, it was run by the Parliament with the king's consent.

It wasn't quite that simple – the king still retained a lot of power, nonetheless the Bill of Rights made it very clear that the king or queen simply could not do whatever he or she wanted.

The English Bill of Rights marked the true beginning of what we now call 'constitutional monarchy'.

George I by Sir Godfrey Kneller, c. 1714. National Portrait Gallery (UK)

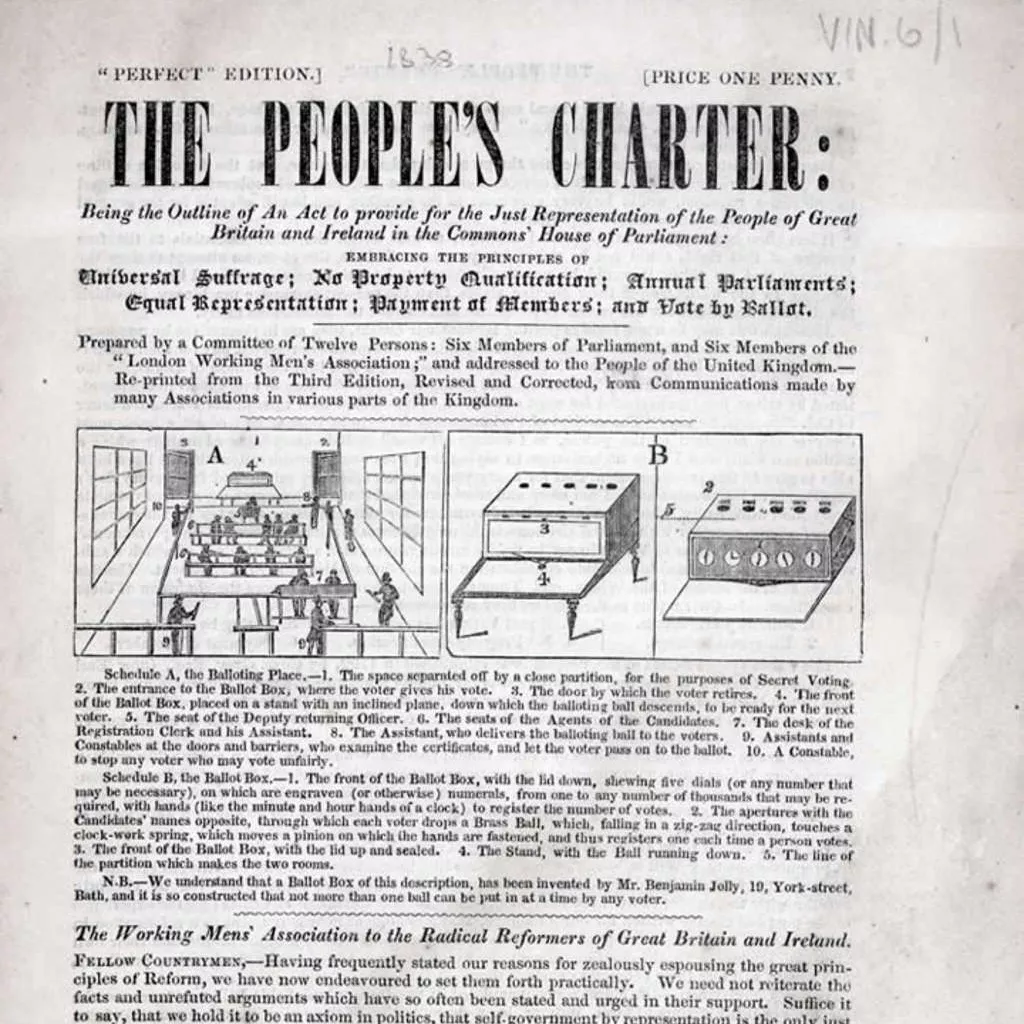

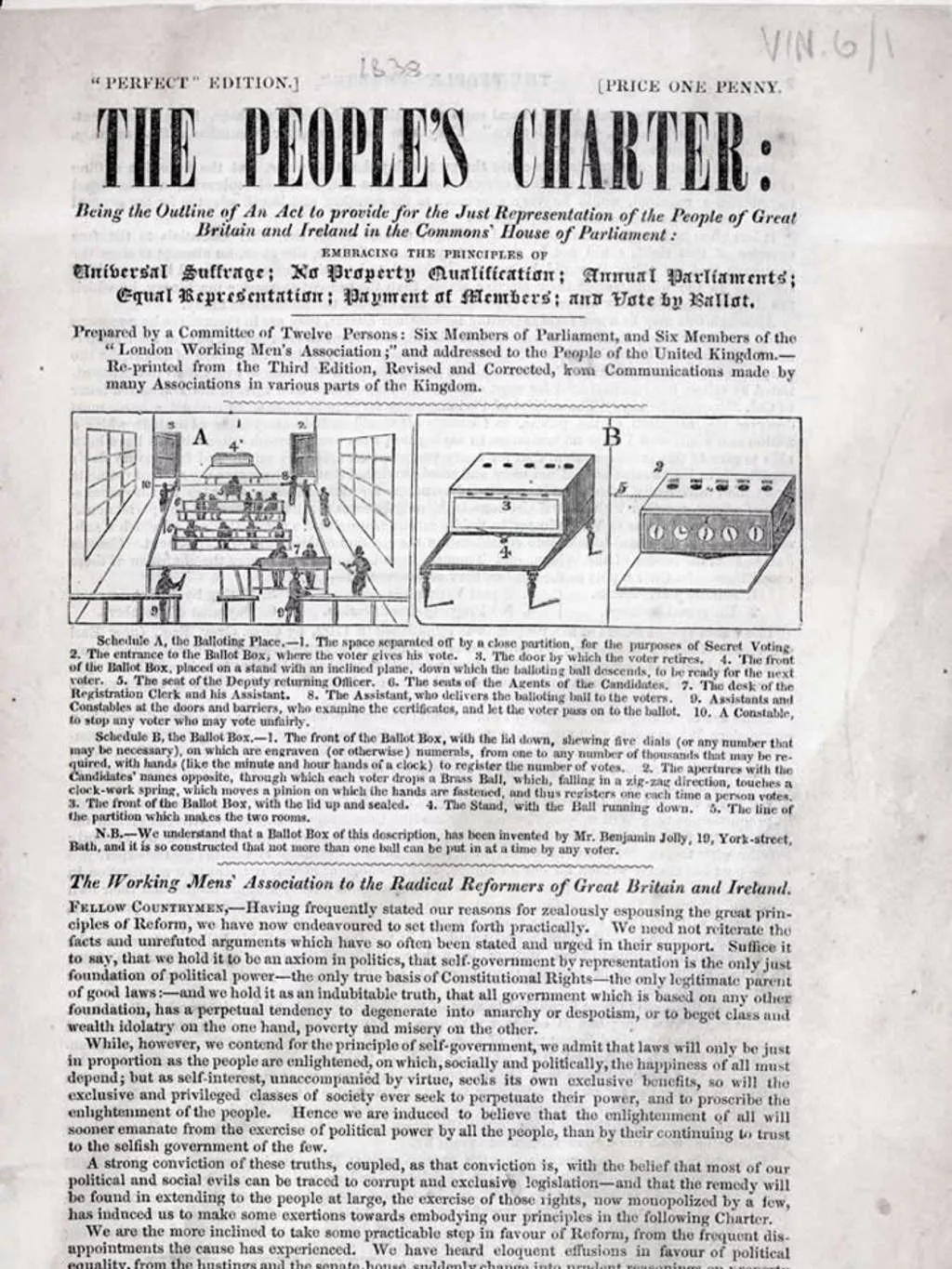

Among other things, the 1838 'People's Charter' called for universal (male) suffrage, regular elections, an end to corrupt 'rotten boroughs' and a secret ballot. Chartist meetings were frequently disrupted by police, and many died fighting for what they believed in. British Library

By George!

In 1714, the crown went to the Elector of Hanover ('elector' in this sense means 'decision-maker', i.e. ruler), who came to England as King George I.

Problem was, George was German and spoke very little English, and had never lived in England or had much understanding of it.

Because of that, his ministers had to do even more of the actual government themselves. This led to the modern system we recognise today, where the parliament and the elected government run the country under a single leader, which from this period began to be known as the prime minister.

Much of what we understand a prime minister today comes from this period of history, with an English aristocrat named Robert Walpole basically inventing the whole concept, as the leader of George I's (and George II's) government.

More democracy, more often

Was England a democracy at this point? Depends who you ask. By our standards, probably not. The right to vote was still very limited.

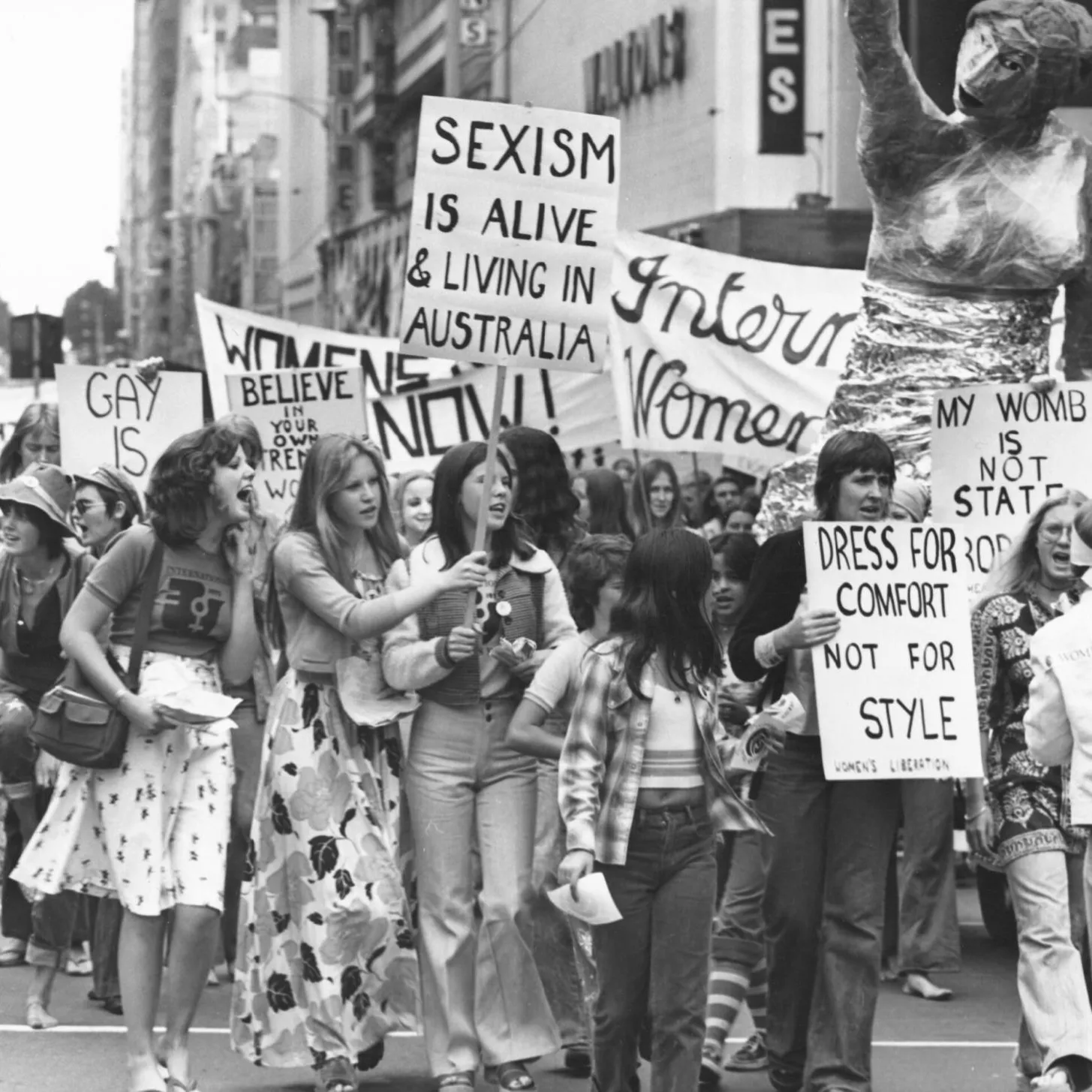

Only men who owned property could vote, and there were some seats where the owner of the land controlled all the voters. It wouldn't pass muster today, and over time people began to agitate for change. One of the main groups pushing reform were the Chartists, so named because they had a charter of demands, who were active in the mid-1800s. It took time and struggle (and blood) but eventually the Chartists got most of what they wanted. Eventually the amount of money or land needed to vote decreased, and over time it became legal for women to vote.

So what?

Enough with the history lesson. Let's take this back to right here and right now. What does all of this stuff about barons and charters, revolutions and popes, have to do with the Australian federal election? The answer is: everything.

Australia has the system it has because it was colonised by Great Britain. It’s even called the Westminster System, after the place the British parliament has met for centuries. When the Australian colonies first started to have their own governments, it was only logical they more-or-less copied what Britain did. It's because of these long-dead figures like Simon de Montfort, Oliver Cromwell and Robert Walpole that we have the political system we have today. Australia has refined and modified it, but the core remains true to the original concept – power is not held by the monarch, but by a parliament elected by the people.

Because of all of this history, we live in a society where one person doesn't make every law. While there are elections of some kind in most countries, less than half the countries of the world have free, competitive, open and transparent elections on a regular basis.