In the running: the Liberals' choice in 1968

- DateTue, 09 Jan 2018

On the ninth of January 1968, John Gorton was elected leader of the Liberal Party, making him Australia’s 19th prime minister. Gorton got the top job under unusual circumstances.

The 1968 ballot was the first modern leadership election. Holt had been elected unopposed in 1966, as had Menzies in 1945, so the party had never had multiple contenders for the leadership before. Labor certainly had; only the previous year, Gough Whitlam faced four challengers when elected ALP leader, but that election had been conducted in relative privacy. The Liberal leadership vote had more publicity, not least because whoever won it would become prime minister. Four men threw their hats into the ring, and each of them had their own unique characteristics and devoted supporters.

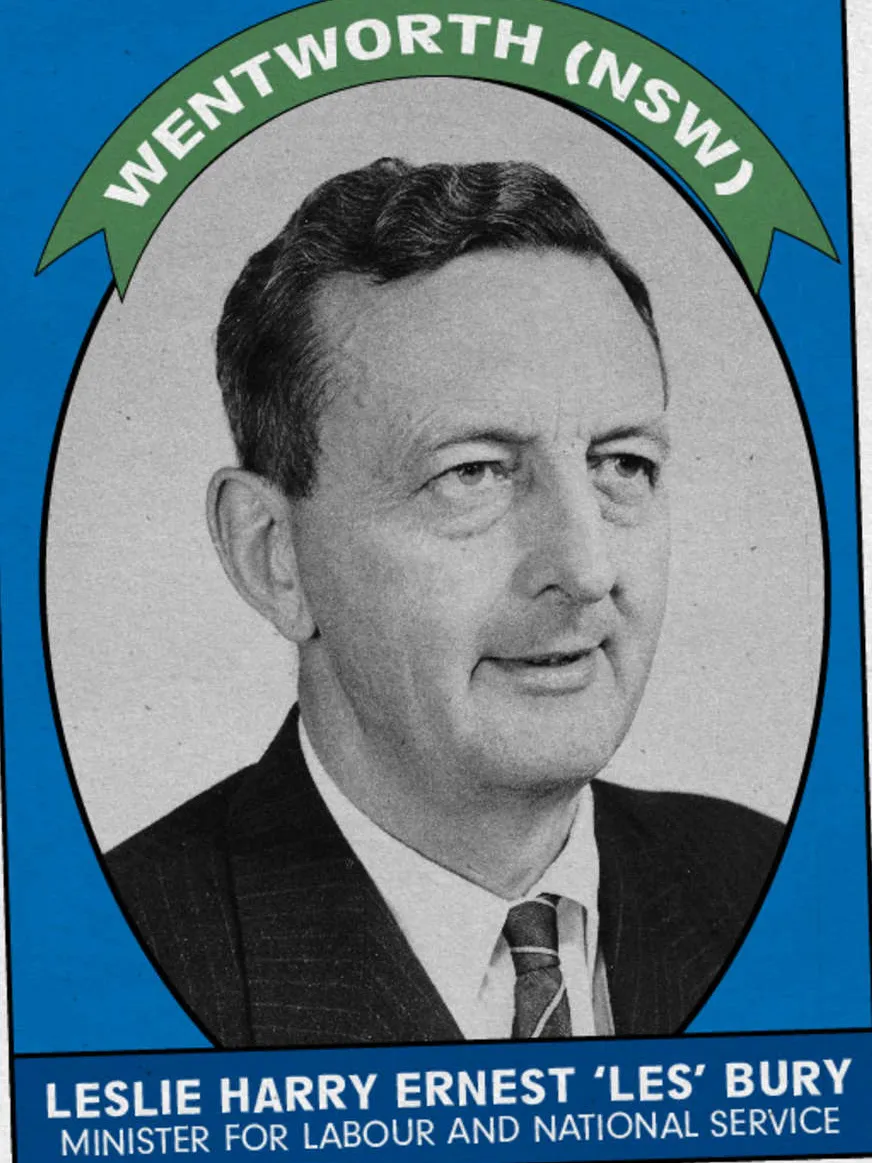

Leslie Harry Ernest ‘Les’ Bury

Age: 54

Electorate: Wentworth (NSW), since 1956

Job: Minister for Labour and National Service

Pros:

- Former Treasury official, strong economic expertise

- Successful administration of First Home Owner’s Grant

- Successful introduction of the National Service Scheme.

Cons:

- Not particularly well-known

- Unpopular with youth due to role in national service about ‘TV performances lacking in human warmth, according to a TV reviewer’.

David Fairbairn

Age: 50

Electorate: Farrer (NSW), since 1949

Job: Minister for National Development

Pros:

- Represented rural seat, good relations with the Country Party

- Thirty years’ experience running a family property

- Believer in state’s rights, like many in the Liberals

- Amiable and popular among his colleagues.

Cons:

- Very little public profile

- Quiet and unimpressive during media appearances.

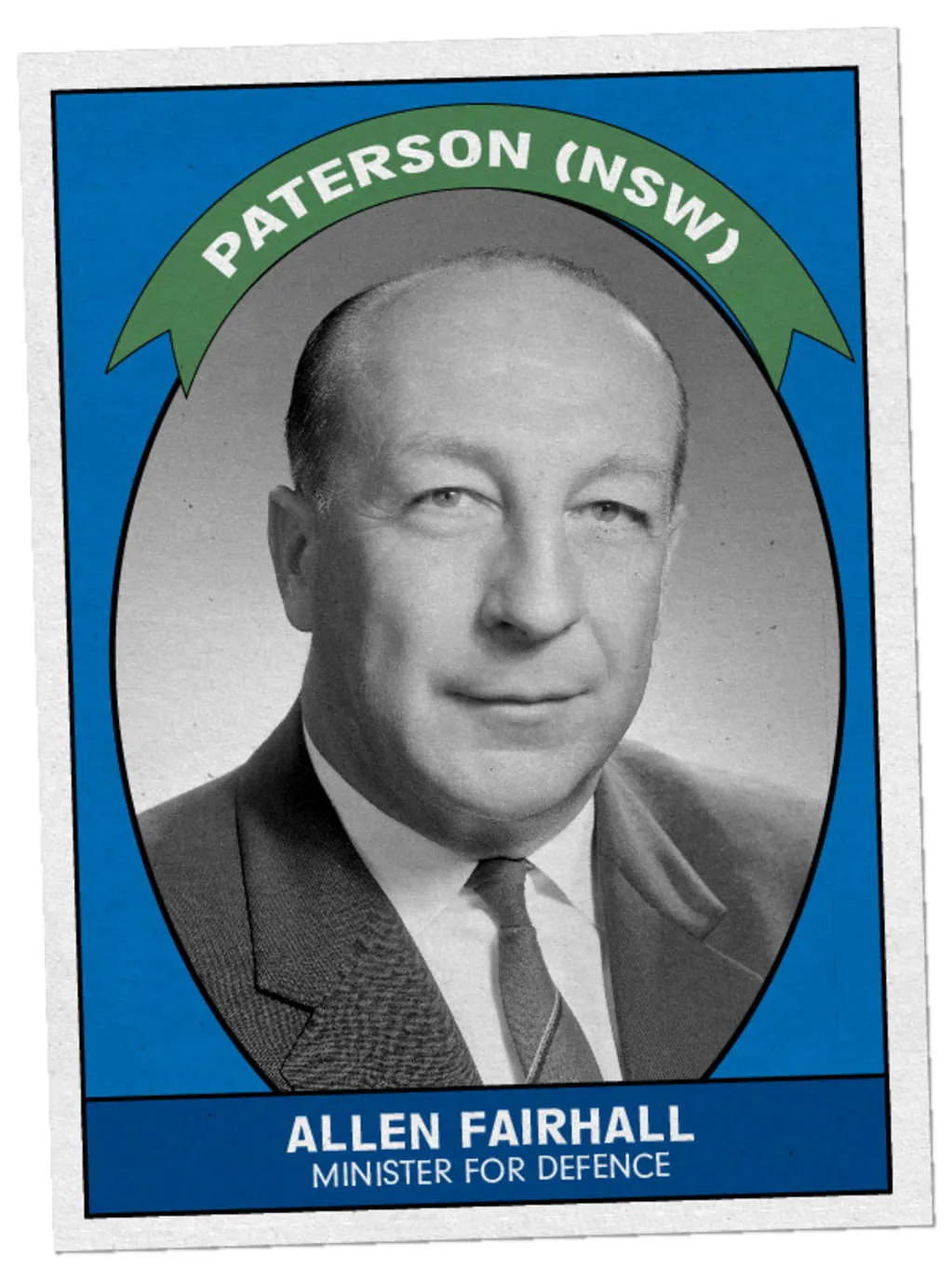

Allen Fairhall

Age: 58

Electorate: Paterson (NSW), since 1949

Job: Minister for Defence

Pros:

- Well-liked in the party

- Well-respected for his competence as Defence Minister

- Known in the community with reasonably high profile

- Strong on national security due to role in Defence.

Cons:

- Didn’t seem to be interested in the job

- Responsible for the purchase of the controversial and expensive F-111 fighter.

John Grey Gorton

Age: 56

Electorate: Senator for Victoria, since 1950

Job: Minister for Education and Science, Leader of the Government in the Senate

Pros:

- Likeable and respected

- Known as a hard worker

- Common touch

- Telegenic and at ease with the camera

- Popular with Senators

Cons:

- Not well-known within the government or among backbench MPs

- A Senator; would have to contest a by-election to serve as PM.

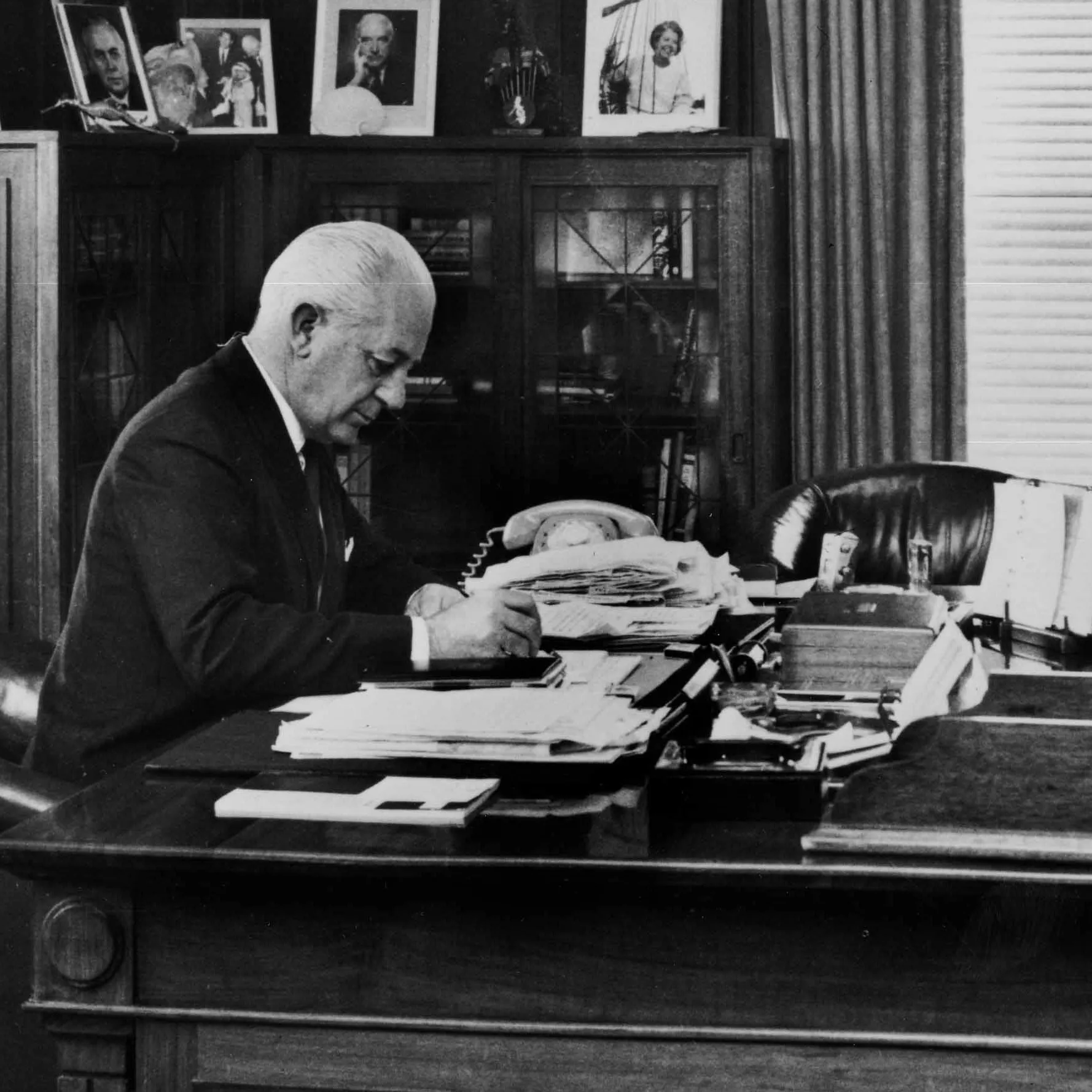

Paul Meerna Caedwalla Hasluck

Age: 62

Electorate: Curtin (WA), since 1949

Job: Minister for External Affairs

Pros:

- Most experienced, political heavyweight

- Strong record as capable and effective

- Said to have the backing of Sir Robert Menzies himself.

Cons:

- Not known to newer, younger MPs

- Seen as stuffy and old-fashioned

- TV reviewers said he was ‘aloof’ compared to the others.

John McEwen

Age: 67

Electorate: Murray (Vic.), since 1949, previously represented Echuca (1934-37) and Indi (1937-49)

Job: Prime Minister (temporarily), Deputy Prime Minister under Holt, Leader of the Country Party, Minister for Trade

Pros:

- Thirty years in politics and long ministerial experience

- Absolute control of the Country Party

- Immensely powerful inside Cabinet

- Deeply respected by both Coalition parties.

Cons:

- Would have to leave the Country Party, unless a compromise was reached

- In his late sixties, close to retirement.

William McMahon

Age: 59

Electorate: Lowe (NSW), since 1949

Job: Treasurer

Pros:

- Deputy and Acting Leader

- Seen as Holt’s heir-apparent

- Easily chosen as deputy in 1966

- Considered a very able and effective Treasurer.

Cons:

- McEwen had effectively vetoed, saying he would not serve under McMahon

- Seen as very ambitious and aggressive with colleagues

- Not popular in Country Party due to trade views

- Notorious for leaking to the press.

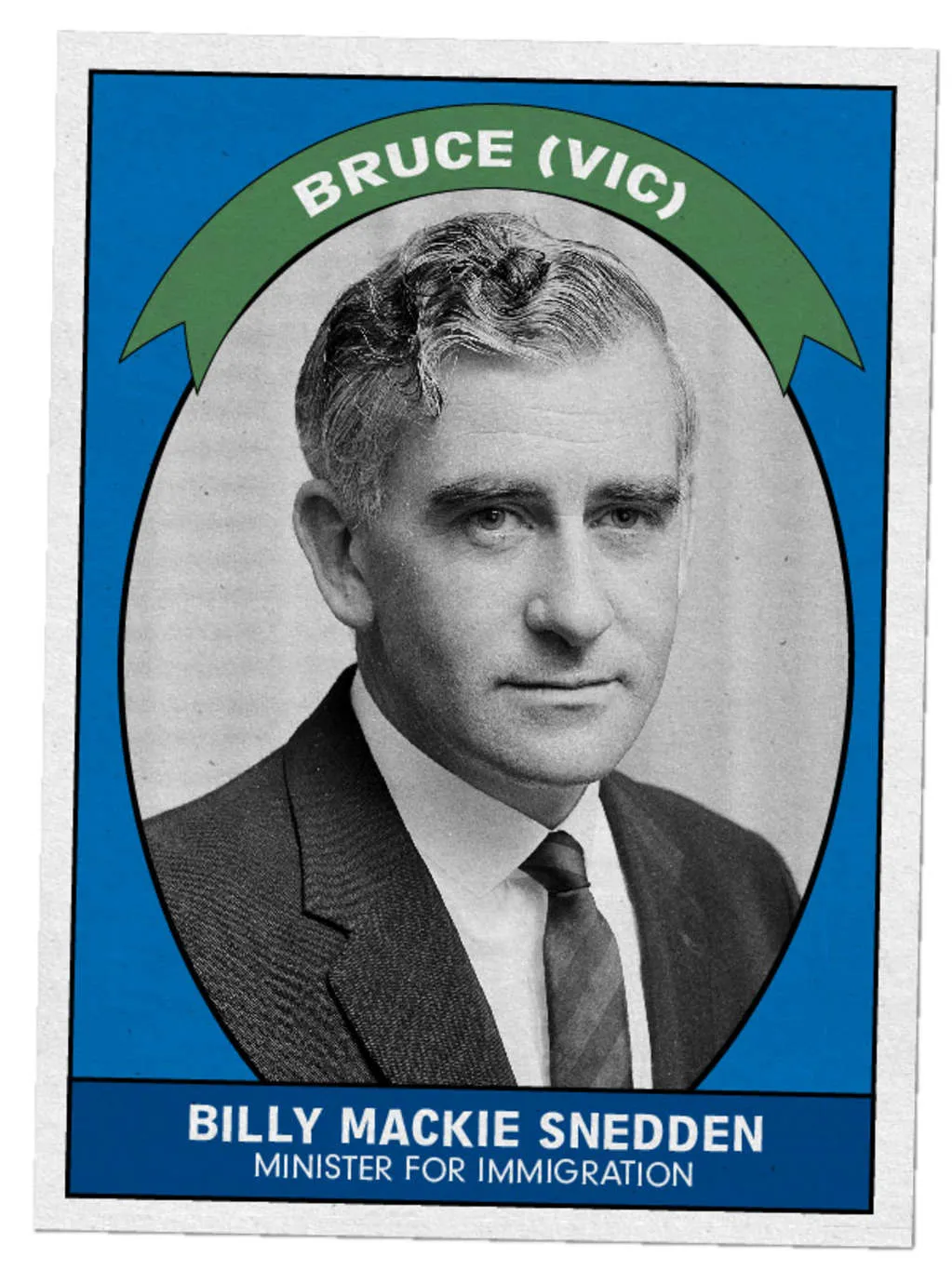

Billy Mackie Snedden

Age: 41

Electorate: Bruce (Vic.), since 1955

Job: Minister for Immigration

Pros:

- Represented young blood, change, and renewal

- Considered a high flier; had already been Attorney-General

- A fresh start and injection of energy and vigour.

Cons:

- Perhaps too young, less experience than many

- Seen by long-serving parliamentarians as an upstart unwilling to wait his turn.

The Campaign

Leadership elections were, and are, conducted behind closed doors in the Party Room. For the first time, however, the media played a significant role in the way the 1968 election was run, and the candidates themselves used the media to make their case. Television was the key to deciding who would take over from the late Harold Holt, because it was from TV that people were now getting their news. Australia wasn’t at the 24-hour news cycle stage yet, but the popularity of the nightly news bulletin and current affairs programs meant that more and more people were seeing for themselves what was happening. Whoever took the top job would need to be someone who could master the medium of television. Gough Whitlam already had – the young, dynamic, telegenic Labor leader was a much bigger threat in the TV age than his predecessor, Arthur Calwell, had been.

The press followed the campaign with interest, reporting every development. Speculation was the order of the day, with thousands of words penned on the relative merits of each candidate. One complication for the press was that nobody knew exactly who the candidates were even going to be. All the names mentioned above were mentioned by the press as potential leaders, but some didn’t make any kind of formal announcement.

Most of the speculation was on McMahon. Would he run, despite McEwen’s insistence that a McMahon government would not involve the Country Party? Many believed he was ambitious enough to do it, and thought he would call McEwen’s bluff (if it was a bluff). But McEwen’s actions probably sealed McMahon’s fate. Had the Country Party boss not intervened, McMahon might have had the numbers, but with McEwen’s pronouncement, his chances dwindled as Liberals looked elsewhere.

Gorton, Bury and Snedden made their intentions very plain to their colleagues. Gorton had the backing of the Chief Whip, Dudley Erwin, who knew what the backbench was thinking. Gorton rang his colleagues asking for their vote, as did some of the others. Jim Killen, at the time a backbencher, later wrote that Gorton rang him and admitted he was not too good at asking for asking for votes. Nonetheless, he became the front runner through dogged campaigning, both personally and from his supporters.

Gorton’s only real rival, other than McMahon, was Paul Hasluck, who simply believed he was the most qualified and reasonable candidate, and didn’t do much canvassing at all. He evidently expected to win based on his record and standing in the party. There was a school of thought at the time, which Hasluck as an old-fashioned sort might have subscribed to, that canvassing for votes was vulgar and undignified.

The Result

At 2:30 pm on a warm Canberra afternoon, the 59 Liberal MPs and 22 Liberal Senators met in the Government Party Room. McMahon, as Acting Leader, was in the chair. After speaking about the tragedy of Holt’s death, the chairman quickly moved to the matter at hand.

Only four people nominated, and McMahon was not one of them. Bury, Gorton, Hasluck and Snedden all rose to put their name forward for consideration as leader. A ballot was held, the final numbers of which were secret. Most estimates put Gorton’s vote at around 35, Hasluck’s at 24, Bury’s at 16 and Snedden’s at 6. Because nobody had a majority, Snedden and Bury were eliminated, and a second ballot was held between Gorton and Hasluck.

At 3:14 pm, Erwin announced the winner – Gorton, by a margin of about 20 votes. The business was concluded, and the Liberals prepared to move forward with a new man at the helm.