1916: Conscription

Last man and last shilling

Date

28 October 1916

Question

Are you in favour of the Government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this war, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within the Commonwealth?

This was a non-binding referendum that was not about a constitutional change.

Result

A slim majority of Australians voted NO and the measure failed. The government honoured the result even though it was non-binding.

NSW

Yes: 356,805 (42.92%), No: 474,544 (57.08%)

VIC

Yes: 353,930 (51.88%), No: 328,216 (48.12%)

QLD

Yes: 144,200 (47.71%), No: 158,051 (52.29%)

WA

Yes: 94,069 (69.71%), No: 40,884 (30.29%)

SA

Yes: 87,924 (42.44%), No: 119,263 (57.56%)

TAS

Yes: 48,493 (56.17%), No: 37,833 (43.83%)

Territories

Yes: 2,136 (62.73%), No: 1,269 (37.27%)

AIF soldiers

Yes: 72,399 (55.14%), No: 58,894 (44.86%)

Total

Yes: 1,087,557 (49.39%), No: 1,160,033 (51.61%)

In 1916, and again the following year, Australians were asked to vote on whether men in National Service, or conscripts, could be deployed to fight overseas in World War One.

Australia had already committed tens of thousands of troops to the war and by 1916 more than 20,000 Australians had been killed. But Britain was crying out for aid and Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes wanted to allow conscripts to be sent overseas to answer the British call. Under National Service, young men could be conscripted but only be deployed within Australia. Hughes wanted to change that.

Hughes didn't need the referendum to get his way, but he wanted to show his party and his opponents that the people were on his side. He toured the country making speeches and passionately asking Australians to vote yes 'for the good of the empire'. His party colleagues, almost all of whom were opposed to conscription, were not impressed. Seeing no alternative, the NSW branch of the Labor Party cast Hughes from their ranks. Despite now being technically an independent, Hughes continued to lead the government.

The Liberal opposition supported conscription, which was popular with many people who considered themselves British. Opponents to Hughes' plan included the Catholic Church, Irish Australians, most trade unions and civil libertarians. The campaign was emotional, and tempers flared on both sides. Accusations of disloyalty or of authoritarianism were levelled. Hughes didn't help his cause by applying regulations and calling up men even before the vote, alienating some of his own supporters.

A very narrow majority of Australians voted against the proposal, and it was rejected. The loss only strengthened Hughes' resolve, and he emerged as leader of a new Nationalist Party, formed with the opposition. As the war continued, Hughes called a second referendum for the end of 1917; the proposal was rejected again, this time by a much wider margin – almost 54% voted no.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes addresses a rally in support of conscription, Martin Place, Sydney c.1916. The large rallies led many to believe a ‘Yes’ vote was a foregone conclusion.

Australian War Memorial A03376

The YES case according to the Argus

'Do the anti-conscriptionists really realise that a war is on and that we are in it? Are their speakers and their writers filled with horror when they contemplate the possibility of a German victory or peace that will condemn a future generation to go through what we are going through? Do they shudder at the memory of German outrages; do they thrill with admiration for the men who are laying down their lives for freedom, for international honour?

Threatened by the war, imperilled by the war? Oh, dear, no; but by the proposals of the Commonwealth Government for carrying on the war on the lines laid down by the imperial War Council. The war? "Oh, bother!" says the anti-conscriptionist. "It is not our war. The Germans don't worry us, but this awful conscription proposal will affect us in business. We, or at least a few of us who keep boarding-houses, may lose quite a number of boarders, and the woman who keeps the store on the corner knows a man at Fitzroy whose brother threatens to curtail his expenditure.

Vote “YES” for Australia, “NO” for Germany.'

Source: Argus editorial, 14 October 1916

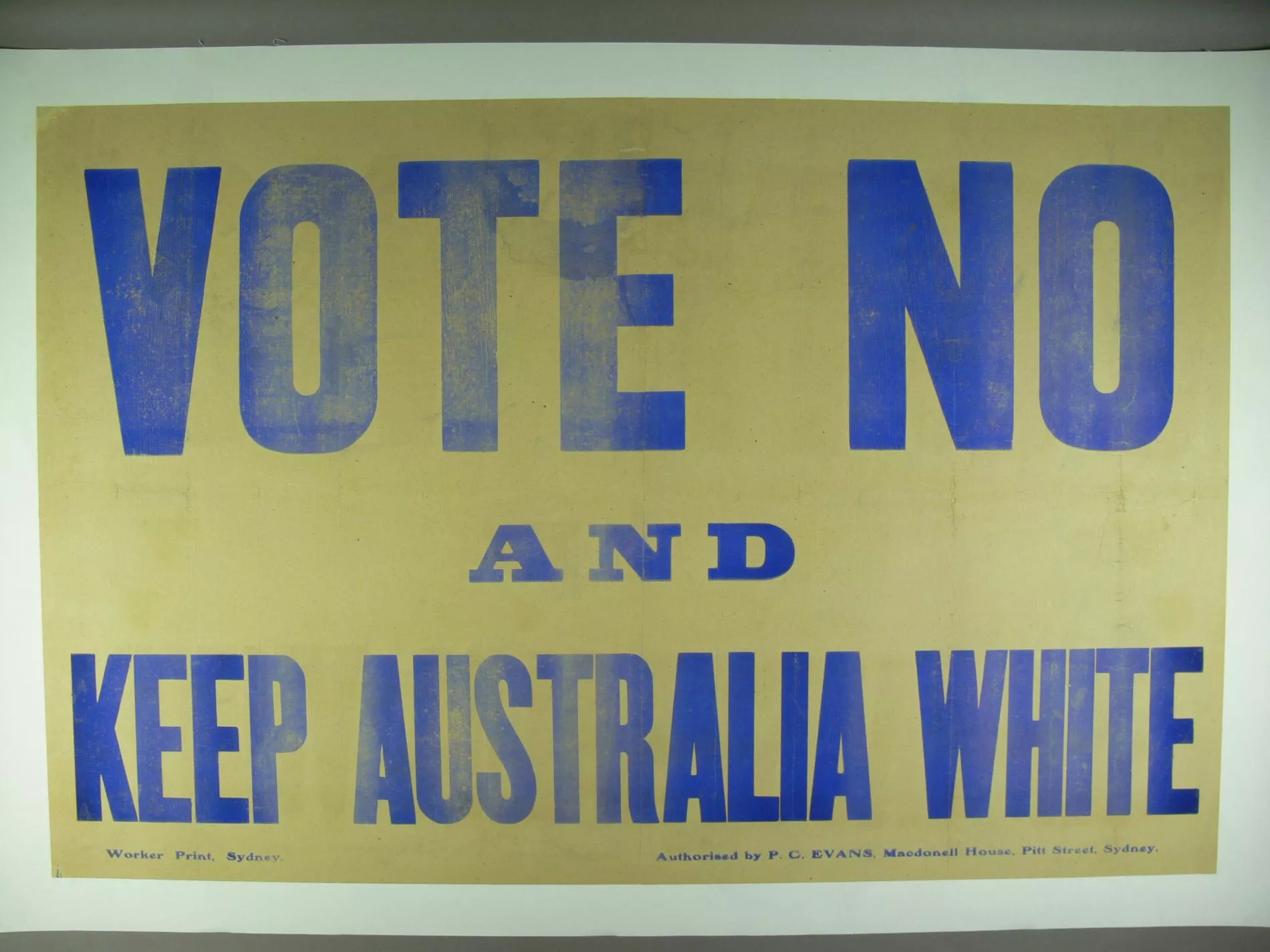

Anti-conscription poster, 1917. Racial prejudice drove at least one of the arguments against conscription – the potential for it to reduce Australia’s white population and force Asian or Pacific labourers to be imported. Museum of Australian Democracy collection 2014-0236

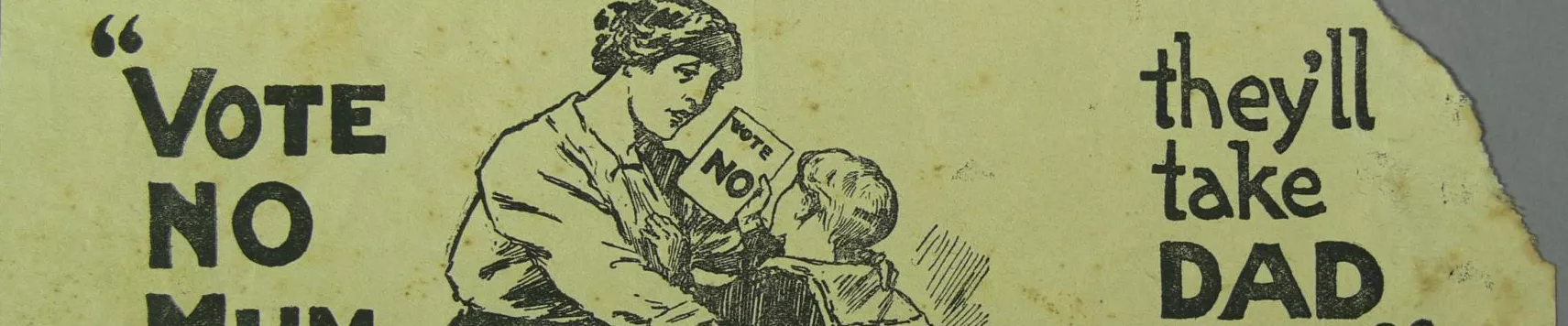

Anti-conscription leaflet from the 1917 referendum. Similar arguments for and against conscription were employed in both 1916 and 1917. Museum of Australian Democracy collection 2016-0103

The NO case according to The Australian Worker

'It would deplete the country of its wealth producers. It would destroy trade and paralyse industry. It would produce chaos in our social order; deport every strong and healthy man to foreign lands; drag the women and children and old men out of the homes to toil in the fields and factories at sweating rates, and subject us to the danger of cheap indented labor [sic] from other lands.

It denies to the individual a will and a soul of his own. It makes a virtual slave of him, for It does not permit him to think and to act for himself, according to his own reason and his own feelings, but violates his personal nature by brute force, and crushes in him every vestige of God given independence.

Once compulsion is introduced, the light of liberty is quenched. ALL OUR CIVIL RIGHTS ARE JEOPARDISED. All our labor [sic] legislation is imperilled. The military authorities assume complete sway.

The Allies do not require more Australian soldiers than the voluntary system will yield, but the whole civilised world would be the loser if Australian citizens were subjected to the iron rule of militarism.'

Source: The Australian Worker, 21 September 1916

Did you know

This was the first Australian referendum that wasn't asking Australians to vote on a proposal to change the Constitution. This vote is sometimes called a 'plebiscite', but at the time it was still called a referendum.

Read more about the difference between a plebiscite and a referendum.