An Australian guide to American elections

- DateMon, 07 Nov 2016

In a speech to the National Press Club, the outgoing US Ambassador to Australia, John Berry, outlined some of the differences of democracy in both countries.

His top three were compulsory voting (voting in the US is voluntary, and candidates spend much time and money encouraging people to vote), time limits on campaigning (the US election cycle often begins more than two years from polling day) and an independent body to oversee elections (most US states have this duty done by local officials).

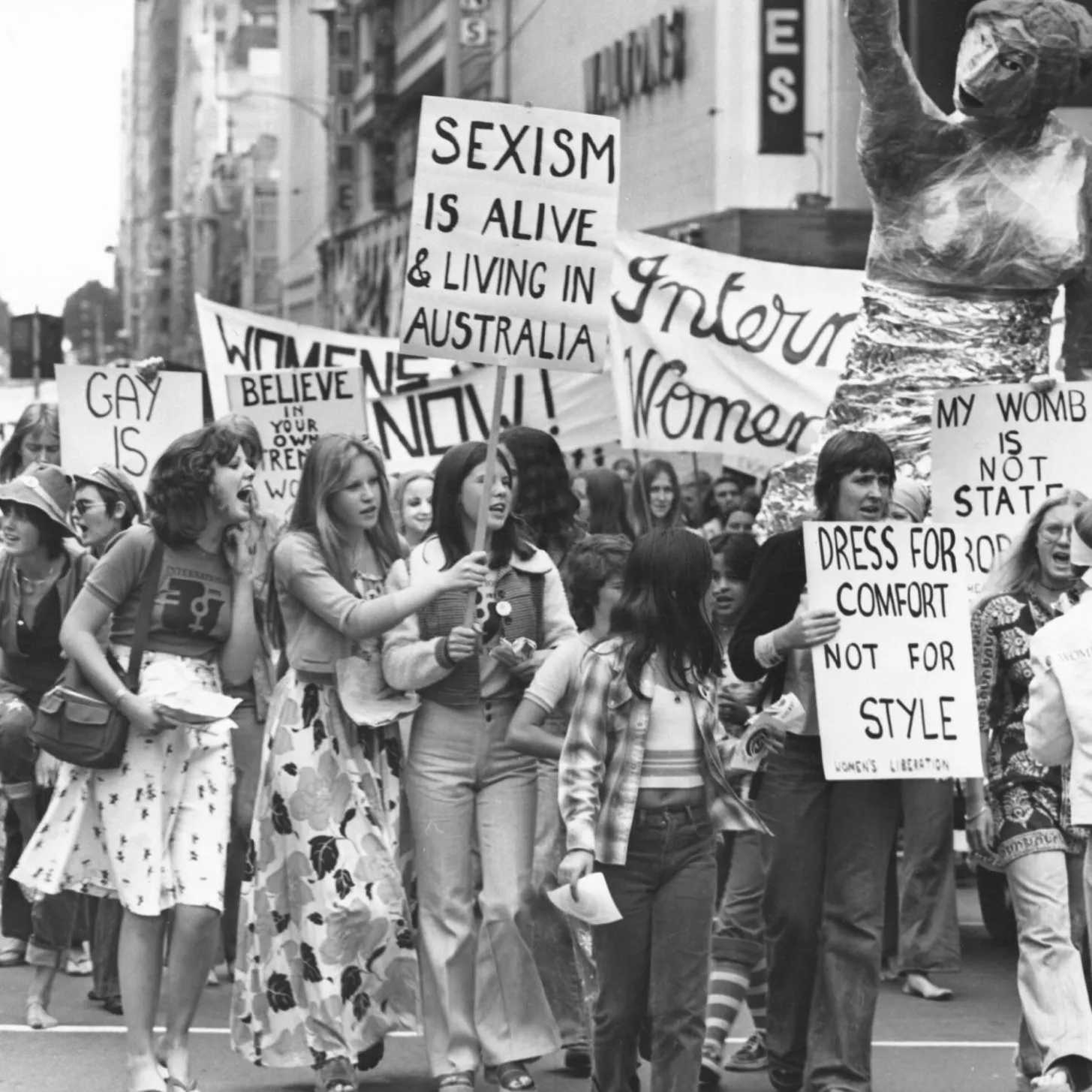

The United States and Australia are two of the world's oldest and most consistent democracies. The US has held free democratic elections longer than most nations, but there, as in Australia, the franchise has continually evolved and expanded from just white landowning men.

America has a long tradition of free elections, and its status as a global superpower means elections there are keenly followed around the world. Very few Americans would be aware Australia had an election in 2016, but almost every Australian could tell you who the American presidential candidates are.

The idea of the 'presidential'-style election, with a focus on the candidate personally instead of their party, has to some extent attached itself to Australian elections. Many aspects of our elections, such as the leaders' debate, concession or victory speeches, and running as part of a leadership 'ticket', are taken from American elections, or inspired by them.

Presidential

The key difference between American and Australian elections is in who has power. In Australia, executive power, while nominally invested in the governor-general, is in practice exercised by the prime minister and their ministers, all of whom are drawn from Parliament. In the United States, the president is separate from the Congress and operates entirely outside it. In Australia the biggest obstacle to the government's agenda is often a hostile Senate, but if the government does not control the House of Representatives, they cannot govern. In America it is reasonably common for the president to come from one party and for Congress to be controlled by another. This was the case for most of Barack Obama's presidency.

Limits and expectations

The presidency isn't, in and of itself, a particularly powerful office. There are very strict limits on what presidents can and can't do. In Australia, similar restrictions exist but the lines between Parliament and government can often seem hard to draw. The American president is often referred to as the 'commander-in-chief', because they are the most senior person in the military chain of command, and have the power to give orders to the armed forces. In Australia, the governor-general is the official commander-in-chief, but in practice the armed services are generally controlled by the minister for defence.

What both the president of the United States and the prime minister of Australia have is a lot of soft power; things people expect them to do, or permit them to do. The president does not actually have the power to run the country alone, but people expect him or her to show strong leadership and make important decisions. The Australian prime minister, whose office is not even mentioned in the Constitution, is certainly nevertheless considered to be someone of power and prestige.

Indirect

One common misconception is that Americans directly-elect the president, as opposed to Australians who choose a Parliament rather than directly choose a prime minister. In reality, the president is chosen by a body called the Electoral College. The Electoral College consists of 538 officials, who are elected by the voters of each state. When US voters cast a ballot, they are actually choosing those electors. It can be confusing, because in some states the electors are listed on the ballot paper, in some states only the names of the candidates are listed, and still others list both.

It's possible for a candidate to receive the majority, or plurality, of votes and still lose. In 2000, Al Gore won more popular votes than George W Bush, but Bush still won the election. To win, a candidate has to win enough states to give them 270 votes in the Electoral College. Some states, like Texas, Alaska and Mississippi, are called 'red states' because they can usually be relied on to vote Republican. California, New York and some others usually vote Democratic, and are called 'blue states' (because convention now uses those colours on maps to denote the winners).

States that are highly contested include Ohio and Florida, and it's in these states that the battle for the presidency really takes place. Often it's these 'swing states' that control enough votes to give victory to one candidate, so they put a lot of energy and money into trying to win them. In 2000 and 2004, George W Bush won the election only because he won the most votes in a single state. The larger states like California, New York and Texas have the most electoral votes.

The closest Australian equivalent would be marginal seats. About a third of the seats in the House of Representatives can be relied on to elect a Labor member, and about a third a Coalition member. The battle for the remaining third is what decides the election, and often the margin needed to win them is very small.