How to change laws and influence people

- DateFri, 04 Apr 2014

In 1895, South Australia became the first place in the world to give women both the right to vote and to stand as candidates for election.

Please note, the Designing Democracy exhibition has now closed.

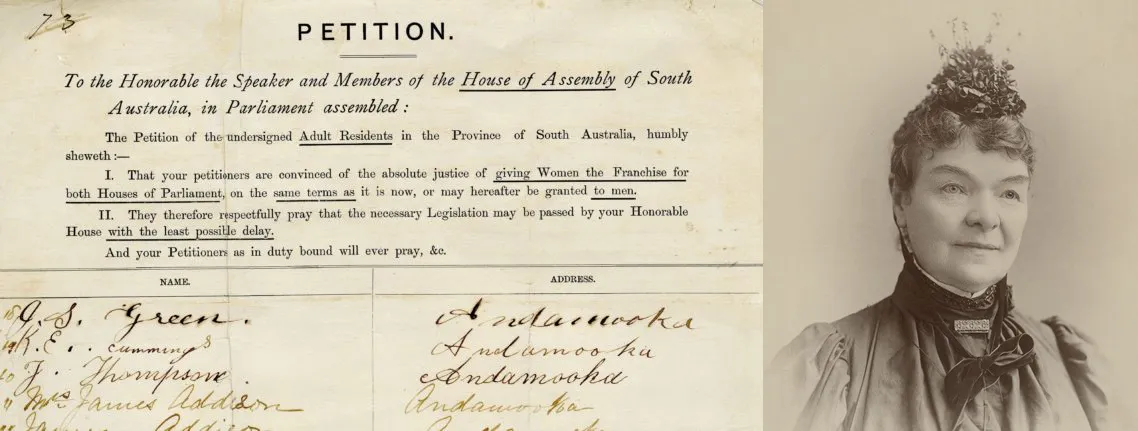

We are proud to now have on display in our Designing Democracy gallery a section of the petition that helped make history.

Part of what is officially known as Petition No. 38 of 1894, the petition panel has been generously lent to us by the House of Assembly of the Parliament of South Australia. The panel was one of hundreds filled with signatures and glued together to form a massive scroll more than 100 metres long. In August 1894, the petition was somehow hauled into the House of Assembly by the Hon. George Hawker, Member for North Adelaide (and father of six daughters). Hawker had to present the petition because at that time, of course, there were no women in parliament.

However, by the time the Bill proceeded through the second reading in the House of Assembly, in December 1894, there were plenty of women in the public galleries. The Adelaide Observer reported:

'Ladies poured into the cushioned benches to the left of the Speaker, and relentlessly usurped the seats of the gentlemen who had been comfortably seated there before. They filled the aisles and overflowed into the gallery on the right, while some of the bolder spirits climbed the stairs and invaded the rougher forms behind the clock.'

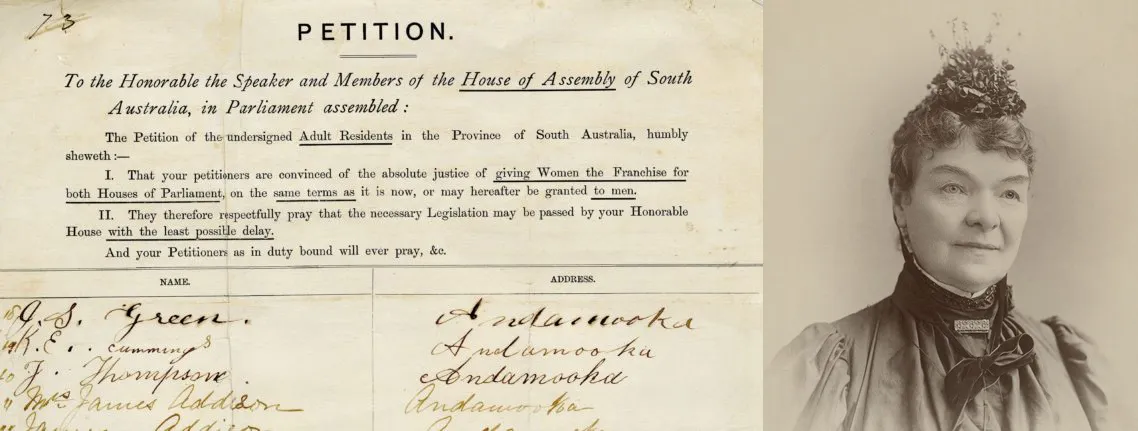

So who were these relentless usurpers, these bolder spirits who invaded this bastion of male privilege? Many of them were members of the Women’s Suffrage League and their network of supporters from the trade union movement, non-Conformist churches, progressive political parties and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Led by the formidable Elizabeth Webb Nicholls, WCTU members collected more than 8,000 of the 11,600 signatures on the petition. Nicholls reasoned that if women could vote, they would help the WCTU achieve its own goal, to curb social problems by prohibiting the sale of alcohol.

Other League activists similarly believed that women’s suffrage would achieve broader benefits. The Women’s Suffrage League had in fact grown from the Social Purity Society, which sought reform on laws relating to women’s social and sexual status. Members of the Society, including the forthright Mary Lee, saw the connection between women’s political, social and economic concerns. Lee co-founded the Women’s Suffrage League in 1888 and the Working Women’s Trades Union in 1890. ‘Feudalism has had its day’, she declared in a letter to the South Australian Register — one of her hundreds of writings and speeches. She continued:

'Could women ever have descended to such depths of misery and degradation if women had a voice in making the laws for women? Let us be up and doing. Let every woman who can influence an elector see that he seizes his vote as a sledgehammer, and goes to the poll resolved to dash from its pedestal of authority this hoary injustice to womanhood.'

Stirring stuff! Although not everyone’s stuff was stirred; at least, not always in the League’s favour. Sneering opponents called the activists ‘shrieks’. The Critic newspaper referred to ‘Mrs WCTU’ and ‘all her crank fads’. Parliamentarian Charles Hussey wrote in the Adelaide Observer on 15 August 1891:

'Poor Mary Lee! How she does froth and foam and stew and scold. I wonder if she manages her household in the same feverish style …. [W]hen women persist in descending from the high and holy position assigned to them by nature and Providence … they forsake the refined sphere of feminine character and influence and forfeit their claim to the honour, respect, and esteem of the sterner sex.'

League supporters were undeterred: Mary Lee (by now in her seventies) called another anti-suffrage parliamentarian, William Blacker, ‘an idiot’. Besides, after years of campaigning and seven previous suffrage Bills, the time for reform had come. In South Australia, women property-owners had been able to vote in local council elections since 1861. Education for girls and women was officially supported. More women worked outside the home, although they often received a fraction of the male wage. They were no longer willing or resigned to accept the political and social structures that limited their participation in public life.

The Women’s Suffrage League and its network coaxed, convinced and rallied others to the cause. Activists spoke at public and private meetings; published articles, books and pamphlets; wrote to the newspapers and, of course, sent petitions to Parliament. League activist and noted reformer Catherine Helen Spence provided support and advice to suffrage movements in New South Wales, Victoria, the US and UK. The determined commitment of South Australian ‘shrieks’ helped change the lives of women across the globe.

The Constitution (Women’s Suffrage) Bill passed on 18 December 1894 and received Royal Assent from Queen Victoria on 2 February 1895. All enrolled women could vote – not just those who owned property – and there was a generous provision for postal voting. Women voted for the first time in a general election on 25 April, 1896. The Adelaide Observer (2 May 1896) reported ‘women, women everywhere … in some instances they literally took the polling-places by storm’.

Looking at the 1894 petition, one can wonder at what ideals, opinions and even arguments drew together this list of spindly signatures from 120 years ago. It is delicate yet powerful proof of peoples’ belief in social justice, equal rights and civil life.