Life of the party – part 1

- DateFri, 11 Sep 2020

Why do we have political parties?

Political parties are a vital part of the democratic system. In this, the first in a series of blogs about parties, their role and history, and people’s experiences with them, we’re going to examine how parties as we know them in Australia today came about.

What’s the word?

WARNING: Paragraph contains Latin.

The word ‘party’, in this sense, comes from the Middle English partie, which means group or side. That in turn was derived from the Latin partīre, which means part or divide (we get the word partition from the same root). So, a political party is a division within politics - one faction or side of the political argument.

The Great Divide

WARNING: Paragraph contains '80s British comedy references.

If you’ve ever watched Blackadder the Third, you’ll know some of this already. Formal parties as we know them today date from the early eighteenth century. Politics in Britain at that time was divided over issues of religion and power. Broadly, factions endorsed either the idea of more democratic rights and less power for the crown, and the opposite (this is a massive oversimplification, but we have to get down to basics here).

From this mess emerged the Whigs, or Liberals, and Tories, names that have kind of stuck around longer than the parties themselves. Blackadder was pretty well on the mark when discussing the rampant corruption and cronyism of the period, but the party organisations themselves survived in different forms.

By the 1770s, philosopher and parliamentarian Edmund Burke was able to describe parties as 'a body of men [sic] united for promoting by their joint endeavours the national interest upon some particular principle in which they are all agreed.'

Early days

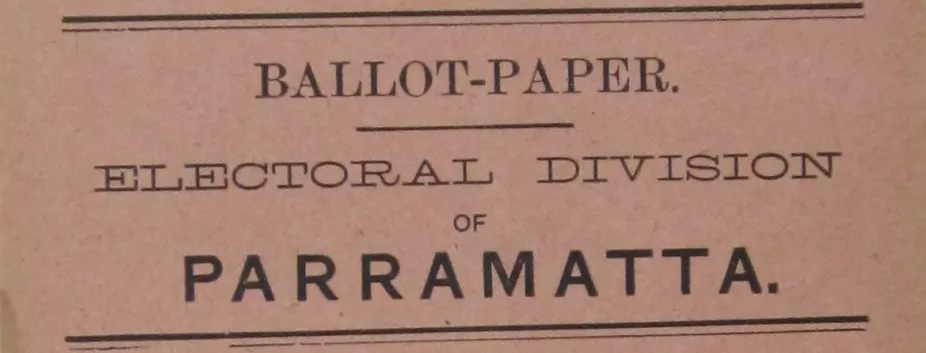

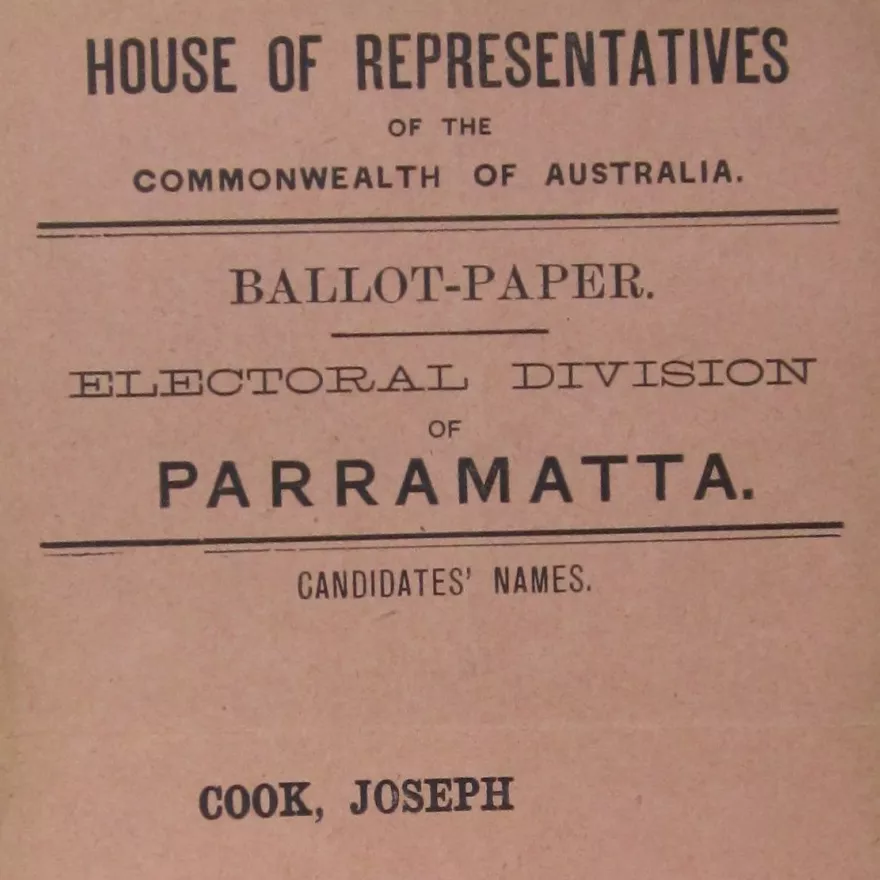

The party system as we know it still hadn’t fully developed in 1901, when Australia held its first election. In some states parties had different names; there is still dispute over whether or not Edmund Barton’s party was the Protectionists, Liberal Protectionists, Liberals, or something else. Really, parties were describing their general philosophy, with trade policy being the big issue of the time. The affiliation of their members was loose at best, but in general Protectionists supported the Barton government and Free Traders didn’t, with Labor controlling the balance of power. Only Labor members committed to the idea of a binding, united front, all taking a pledge to abide by the party’s decisions or face expulsion. This was done to give them more voting power, and was seen as a way of punching above their weight.

This worked so well for Labor that over time the other parties began to do something similar. None of the parties had a majority, so there were constant shifts in alliance and negotiation, to the point it made Alfred Deakin irritated. He frustratingly described the three parties as 'three elevens', referring to cricket teams, asking Australians to imagine a cricket game with three teams instead of two.

Then there were two

Eventually, from 1910, the system settled down into a 'two-party' system. This means that politics is largely seen as a contest between two opposing parties, and while smaller parties can and do get elected, they don’t usually get to become part of the government. Since 1910, one of those two parties has changed multiple times, and the other has always been Labor. The modern Coalition of the Liberals and Nationals evolved since World War II, and it’s the Labor-Coalition dynamic that makes up most, but not all, of our modern political discourse.

Parties today

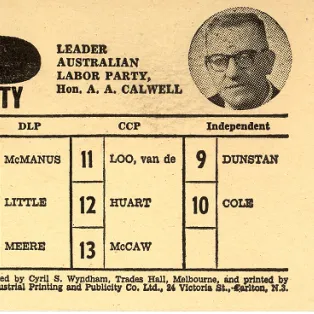

More and more parties are being elected to the Commonwealth Parliament than at any time in history. This is partly due to political factors and partly due to the electoral system – the voting system used for the Senate makes it relatively easy to get elected as a minor party. Recent changes to the rules may mean we see fewer ‘microparties’ elected on a tiny number of votes, but all trends suggest diversity of political thought is increasing.

The changing times

Parties that remain static risk electoral oblivion. Parties across the spectrum have changed, or are changing, the way they operate to remain relevant and attract new members. For instance, since 2013, Labor members have had an official voice in choosing the party's leader. In some ways this resembles the ‘primary elections’ held by parties in the United States, although the rules are quite different. Other parties have experimented with similar arrangements or discussed them at the very least. In the future, what a political party does and how it operates will likely be very different.

In part 2, we explore what parties actually do, and why people become involved with them. How do parties work, and what does it matter to you?