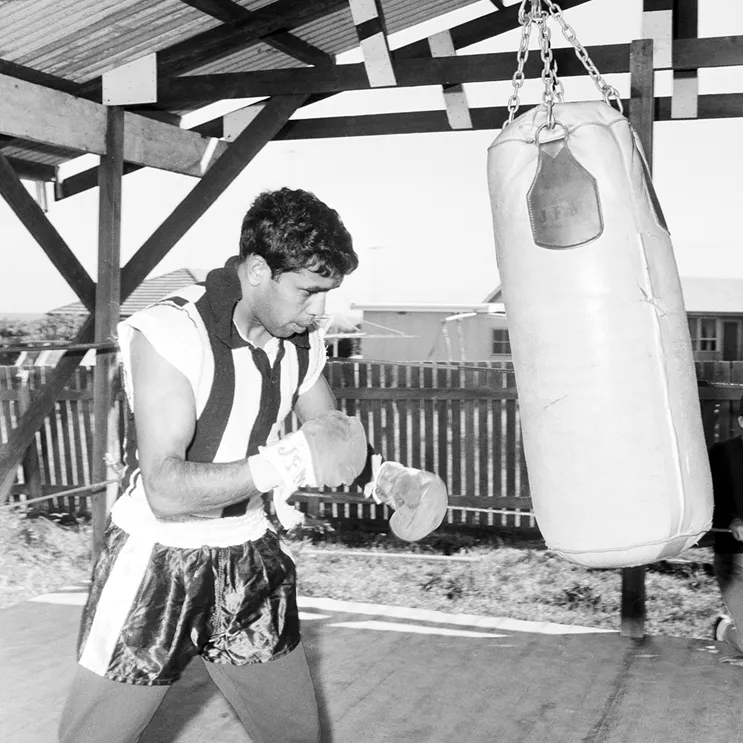

Lionel Rose's world championship 50 years on

- DateMon, 26 Feb 2018

In 1968, Lionel Rose became the first Aboriginal Australian to win a world championship.

First Nations readers are advised this article includes the names and images of deceased people.

On 26 February 1968, Lionel Rose defeated Masahiko ‘Fighting’ Harada in Japan for the world bantamweight boxing title. His success occurred nine months after the historic referendum of 1967, which gave the Commonwealth Government the power to legislate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and to include all Indigenous Australians in official estimates of the Australian population.

Rose’s win was a huge event for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians alike, but more so for Aboriginal Australia.

Warren Mundine, in his autobiography In Black and White (2017), recalls:

One hundred thousand people crowded into the centre of Melbourne CBD to welcome Rose back to Australia. On remembering this enormous excitement it is worth reflecting on the progress made in Aboriginal affairs in the decades since.

In 1968, when Lionel Rose became a household name, there were no Aboriginal land rights in law. Today, more than 20 percent of Australia, about 1.6 million square kilometres, is owned by Indigenous peoples under native title and statutory land rights schemes. The first federal land rights legislation passed through parliament in 1976.

Progress would not have happened without the determination and struggles of Aboriginal people themselves, going back to great leaders like William Cooper, Fred Maynard, Jack Patten, Margaret Tucker, Pastor Doug Nicholls, Pearl Gibbs, Oodgeroo Noonuccal, Bill and Eric Onus and Shirley Smith (‘Mum Shirl’) who campaigned with their non-Aboriginal supporters like Faith Bandler and Jessie Street.

Two years prior to Rose’s championship, headlines were made when Charles Perkins became the first Aboriginal man to obtain a full university degree. Today, there are 35,000 Indigenous Australians with university degrees and 18,000 currently enrolled in university courses.

In 1971, the first national census conducted after the 1967 Referendum found that there were 120,000 Indigenous people in Australia. Today, there are 650,000, mostly resident in cities and regional centres.

In 1968, when Rose won the title, there were no Indigenous Australians in the federal parliament, and never had been. In 2018, there are four. While Indigenous people constitute 2.8% of the Australian population they make up 2.2% of federal parliamentarians.

There are many other areas where progress has occurred but we must continue to confront the negatives: the on-going scandalous and disproportionate poor health and high suicide rates, absence of economic opportunity, poverty, racism, domestic violence, high mortality, low literacy and numeracy, and high overcrowding. Rates of child abuse and adult imprisonment have increased. Indigenous Australians are 27% of the prisoner population in Australia.

An Aboriginal woman is 34 to 80 times more likely to be subject to violence than non-Indigenous women. Indigenous children are seven times more likely to be receiving child protection services than non-Indigenous children.

It should be pointed out that the problems particularly affect remote communities and are not as bad in the urban and regional centres, where the majority of Indigenous Australians live and work. This has led to the Yothu Yindi Foundation recently calling on the Productivity Commission to change its definition of ‘Aboriginality’ in the distribution of GST revenue to focus on disadvantaged remote communities.

Lionel Rose was one of our greatest boxers and sportspeople. Five decades on, there are many other champions of Indigenous background in a range of sports. But so too there are now surgeons, academics, university administrators, writers, mathematicians, singers, judges, dancers, technologists, fashion designers and models, scientists, film makers, actors, senior public servants, dentists, pilots, celebrated musicians and artists and prominent journalists.

As the best in his field, Rose was a role model. Despite the on-going problems of disproportionate disadvantage, there is no shortage of positive role models today. But there is still a very long way to go.