What does one do after leaving the top job?

- DateTue, 22 Sep 2015

One characteristic shared by almost all 28 former prime ministers is a marked reluctance to relinquish the office.

What does one do after leaving the top job in the country? What else is there to aspire to?

For some, it was all about planning and plotting to regain the top job. Leaving aside the peculiar circumstances of the first decade of the Commonwealth, this certainly applied to Billy Hughes, who hoped time and time again that he would be recalled. He never was, but spent the next 30 years in Parliament plotting and hoping. Stanley Bruce, who succeeded Hughes, also sought to position himself for another tilt. James Scullin, Robert Menzies, Ben Chifley, Gough Whitlam and Kevin Rudd also never accepted losing the job as final. Menzies, of course, returned in triumph in 1949, Gorton’s hopes remained just hopes, Scullin, Chifley and Whitlam each fought on as Opposition Leader for one more election, and Rudd wrested back his old job after a long and ugly campaign.

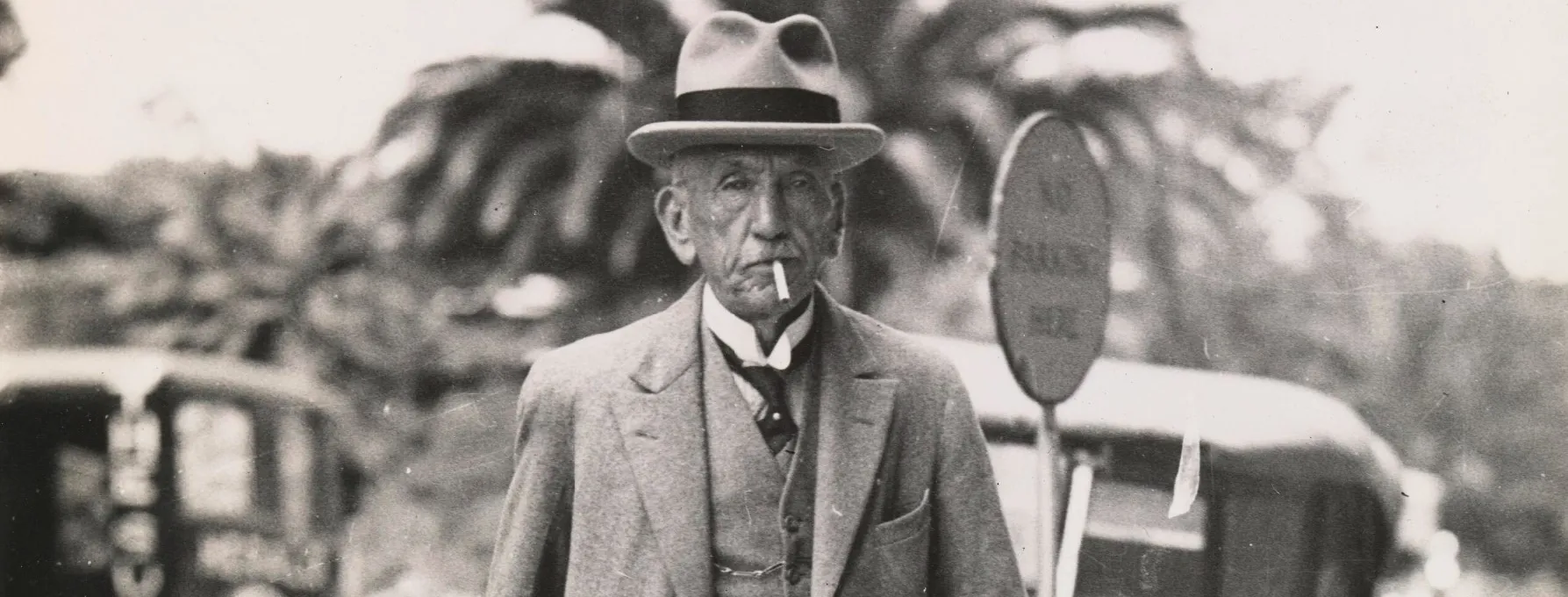

Alfred Deakin

With Edmund Barton out of political life on the bench of the High Court, Deakin was the natural and undisputed successor, the legislative dynamo as Barton’s Attorney-General in setting up the machinery of the new Commonwealth. But what he inherited was flawed and he was quick to point out the shortcomings of a political system that delivered three parties of almost equal number, which he aptly characterised as a game of cricket in which three elevens take the field. It was in many respects unworkable, and a little more than 200 days into his term Deakin, almost whimsically, resigned when he found himself without the numbers on the floor of the Parliament.

Deakin was neither dismayed nor surprised at the turn of events; he quite clearly saw them coming, telling Parliament:

It was effectively a tactical retreat: he knew that the prime ministership might well return to him in different circumstances, but in the meantime the king was content to step aside and become king-maker, just as he had been instrumental in Barton’s becoming prime minister, and would also in the coming years engineer the rise of both George Reid and Andrew Fisher. Just as decisively, Deakin would also unmake the governments of Chris Watson, Reid and Fisher. If there were indeed three elevens on the field, Deakin himself added a further dimension of complexity to the situation: captaining one side and also acting as umpire.

Deakin’s second term (1905-08) was far more substantial, both in terms of tenure and legislative achievement, but it also ended, in less salubrious circumstances, in defeat in Parliament. Again, Deakin was down but not out, returning finally in 1909 at the head of the Fusion Liberal Party, a merger of his own Protectionists and his former foes, the Free Traders. Three elevens had been reduced to two, but when he was defeated at the 1910 election it really was the end with both his health and his ambition faltering.

George Reid

The jolly, rambunctious figure of Reid was a cartoonist’s delight, but behind the shambling gait and the persiflage lay a sharp political mind and a driving ambition. Far more than the three prime ministers who had preceded him — Barton, Deakin and Watson — Reid was the one who desperately wanted the job. An unexpected turn of events in New South Wales in 1899 had seen him lose the premiership, the possession of which the following year would almost certainly seen him become the first prime minister. But having served as Opposition Leader from the formation of the Commonwealth, he seized his opportunity in 1904 when the short-lived Watson government fell. But his ten-month tenure is flattered by a long parliamentary recess after which, to Reid’s bitter chagrin, Deakin turned on him and replaced him. The ever resourceful Reid, by now acknowledging that the tariff issue had been settled, promptly re-invented himself as an anti-socialist, the platform on which he fought the 1906 election. His defeat was the last roll of the dice.

Andrew Fisher

Defeated in Parliament in 1908, Fisher knew the electoral tide was running Labor’s way, and he returned in triumph at the 1910 election. A narrow loss in 1913 did not extinguish the flame and he returned for a third term at the double dissolution election in 1914, later stepping down in favour of Billy Hughes.

Billy Hughes

It is doubtful if any former prime minister was as deeply immersed in intrigue as Hughes; certainly no one else comes near to nurturing ongoing prime ministerial ambitions for such a length of time. Defecting to the Nationalists after the conscription issue split the Labor Party in 1916, Hughes was effectively deposed in 1923 when the Country Party refused to accept him. Simmering on the backbench for the remainder of the government of Stanley Bruce, who had replaced him, Hughes gleefully helped orchestrate the revolt that led to Bruce’s defeat in 1928. First, he had some hope that he might be chosen to replace Bruce; he also, less realistically, thought the ALP might forgive him and restore him to the job. As a minister in the Lyons government in the 1930s, Hughes liked to think he still carried the field marshal’s baton in his rucksack. In 1941, when the United Australia Party turned against Menzies and deposed him, Hughes was in deep with the plotters — and again he hoped for a recall. It was Country Party leader Arthur Fadden, however, who emerged to succeed Menzies, but still Hughes was not done, even returning briefly as leader of the UAP at the age of 80.

Stanley Bruce

Bruce was the first prime minister to lose his seat. No sooner had the votes been counted in the 1928 election, than Bruce was writing to friends about a comeback. In 1931 he returned to Parliament, but Prime Minister Joe Lyons sent him to London as High Commissioner. He was scathing in private of Lyons and the quality of his government and for a time entertained and even explored the prospect of returning, improbably, as a non-party prime minister.

Robert Menzies

Driven from office in 1941, and fighting an anti-Menzies campaign emanating from Sydney, Menzies, however, was never one to fade into the sunset. Pitching a personal appeal to the ‘forgotten people’ and fashioning a new political party to his own specifications, his ambition, hard work and self-belief were handsomely rewarded with a return to office in 1949 and an unbroken reign of 16 years that is unlikely ever to be matched.

James Scullin, Ben Chifley, Gough Whitlam

This trio of former ALP prime ministers each led the party to a subsequent election as Opposition Leader, but in each case the wind had gone from their sails. Scullin was unwell and chastened by his term in office, Chifley was in poor health and died soon after while Whitlam, shattered by the events of 1975, was a shadow of his former self.

John Gorton

Deposed by his party in 1971 in favour of Bill McMahon, Gorton remained in Parliament in the hope that the Liberal Party would see its error. He had, at most, two supporters. After the Coalition’s defeat in 1972, Gorton saw Billy Snedden floundering as Liberal leader and again hoped for a recall. It is doubtful if anyone else shared the view.

Kevin Rudd

Rudd broke the tradition, set by Malcolm Fraser in 1983, of defeated prime ministers leaving political life altogether. Bob Hawke and Paul Keating bowed out immediately while John Howard lost his seat in 2007. After being dumped in favour of Julia Gillard in 2010, Rudd devoted every waking hour (and possibly every sleeping hour as well) to finding a way back to the job he believed was rightfully his. Despite one failed challenge and another challenge that failed to eventuate, he eventually returned in 2013 to preside, briefly, over the carnage that was largely of his own making.

Tony Abbott

Deposed by Malcolm Turnbull, Abbott announced he would remain in parliament and, as at September 2015, had gone quietly to the backbench.

As a footnote, the country’s shortest serving prime minister, Frank Forde, who filled the post for a week in 1945 between the death of John Curtin and the election of Ben Chifley, was not content with mere interregnum status. He contested the ballot against Chifley and two others, winning a respectable 15 votes. Chifley won with 45.