How Billy Hughes lost the 1916 conscription referendum

- DateFri, 04 Nov 2016

Australia was one of the very few countries within the British Empire that failed to adopt conscription during World War I.

Why did the Prime Minister W. M. (Billy) Hughes fail in his two attempts to introduce conscription for overseas service?

There is no single answer, but most important was the dominance of the ALP within the federal government. Labor had won a majority in both houses of parliament at the double dissolution election of September 1914; and while having a parliamentary majority is normally an advantage for any government, in the case of conscription, it was a liability. The industrial labour movement which underpinned the ALP was a natural constituency against military conscription because the left feared that it would be a precursor to industrial conscription. Ironically, then, the very strength of Hughes’s political base was a barrier to his introducing conscription. It blocked the path that every other imperial government adopted, introducing conscription by legislation. Hughes knew that if he introduced a bill seeking to amend the Defence Act of 1903 which limited overseas service to volunteers, it might get through the lower house with the help of the Liberal opposition, but the Senate with its large Labor majority would almost certainly reject it.

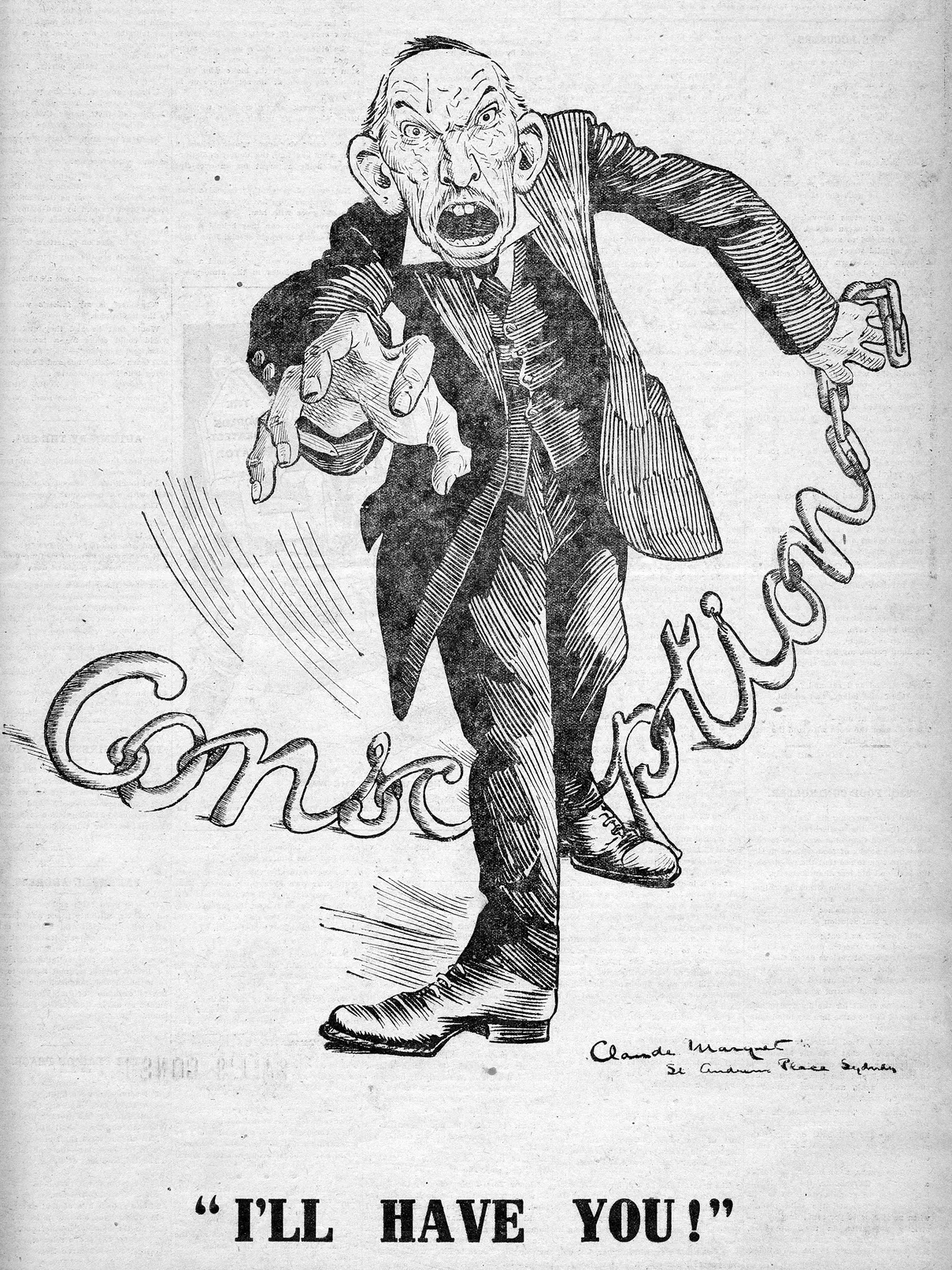

So Hughes decided to take the matter to the people to secure a popular mandate with which to confront his opponents. He was the only imperial leader who was forced to bypass parliament and put the inherently contentious matter of conscription to a direct popular vote. Of course Hughes thought he would win. But we need only to look at Brexit, to see that referenda campaigns have a life of their own. If the debates that precede them are long, and the 1916 conscription campaign lasted for nearly two months, they can slip out of the control of the politicians who initiate them. They become a vehicle for the expression of economic grievances and political discontent not necessarily related to the issue under debate. So it was with Australia in 1916 and 1917.

Hughes’ chances of winning were also compromised by the timing of the 1916 campaign. Both the British and New Zealand parliaments debated the matter of conscription before the monumental battle of the Somme had begun. The Australian public, in contrast, was asked to vote on conscription during the Somme while the news of its massive casualties was fresh. These losses, which the Yes case thought made conscription essential, invested the debate about conscription with the passion and hysteria of mass grief. It was as if the anger and despair against a war that seemed beyond the control of any politician or military commander to end was being deflected against political opponents at home. What might have been the result of the conscription vote if Hughes had held it in the first half of 1916, not the last? Instead of doing this Hughes spent six critical months in London, during which the Easter Uprising occurred in Dublin, an event which radicalized at least some Irish-Catholic Australians.

Even if the Australian vote had been held earlier, it would have had to contend with the strength of the industrial labour movement, another distinctive element of the Australian political scene. The powerful trades union had a dynamic press and a capacity to mobilize protest on the streets. They also dominated the ALP at the local branch level, controlling pre-selection of Labor parliamentary candidates. Put another way, Hughes was campaigning for conscription having lost much of the support of his own political base. This cannot be said of any other imperial leader.

Hughes, it must be said, played his rather difficult hand badly. Opposition tended to fuel his authoritarian tendencies, and he used the emergency powers of the War Precautions Act in a partisan manner, restricting the freedom of speech, assembly and press of anti-conscriptionists. His heavy-handed use of state power seems to have persuaded some wavering voters to oppose conscription, particularly when Hughes used the powers that he did have under Defence Act to call up men in late September. Many Australians thought was a pre-emptive and arrogant prejudging of the result of the referendum.

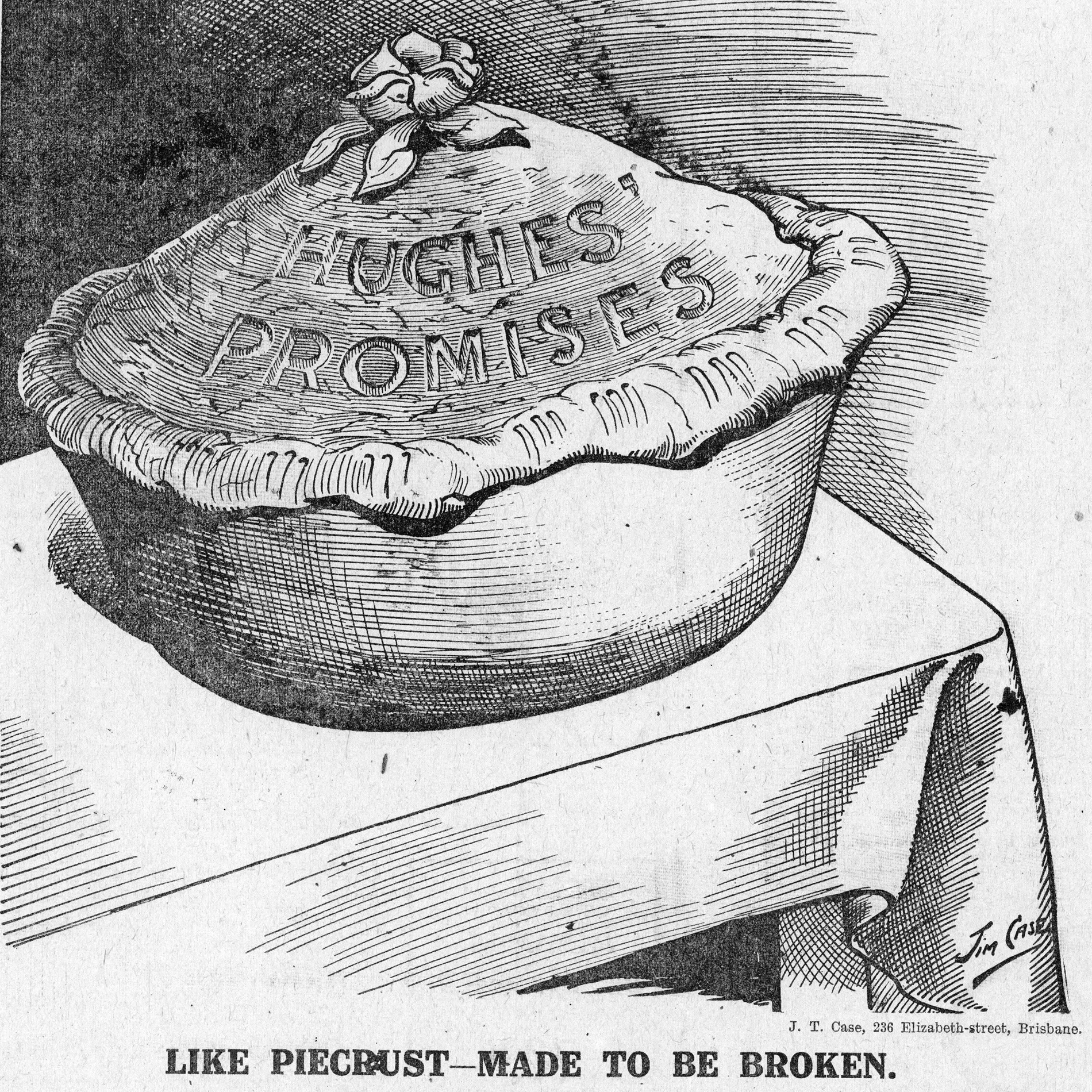

Finally, Hughes fuelled mistrust among wavering voters by failing to be precise about how conscription would be implemented. The British conscription legislation provided detail about the treatment of conscientious objectors and the New Zealand bill was an astute and masterly compromise in which men would be called up only if regional quotas for volunteers failed to be met. The question put to the Australian public in 1916, in contrast, was opaque. In the second conscription campaign Hughes did provide more detail, proposing a scheme along the lines of the New Zealand one, but the 1917 referendum was probably doomed to fail, given that little had changed since 1916, other than the number of casualties— which had only soared in the terrible battles of 1917.

Could a more nuanced politician than Hughes have won the conscription referenda? The margin for Yes in 1916 was only 3.2 per cent of valid votes cast; so it is possible that the Yes campaign was winnable. We will never know; but what we might conclude is that if the Yes campaign had prevailed, making the Australian Imperial Force a conscript army, Australia might not have developed such a resilient mythology about the men who did volunteer. And our leaders today might be telling a very different story about the place that the Anzac legend, a cult of the volunteer, plays in our national identity and memory of war.