On Hansard

- DateSat, 04 Mar 2017

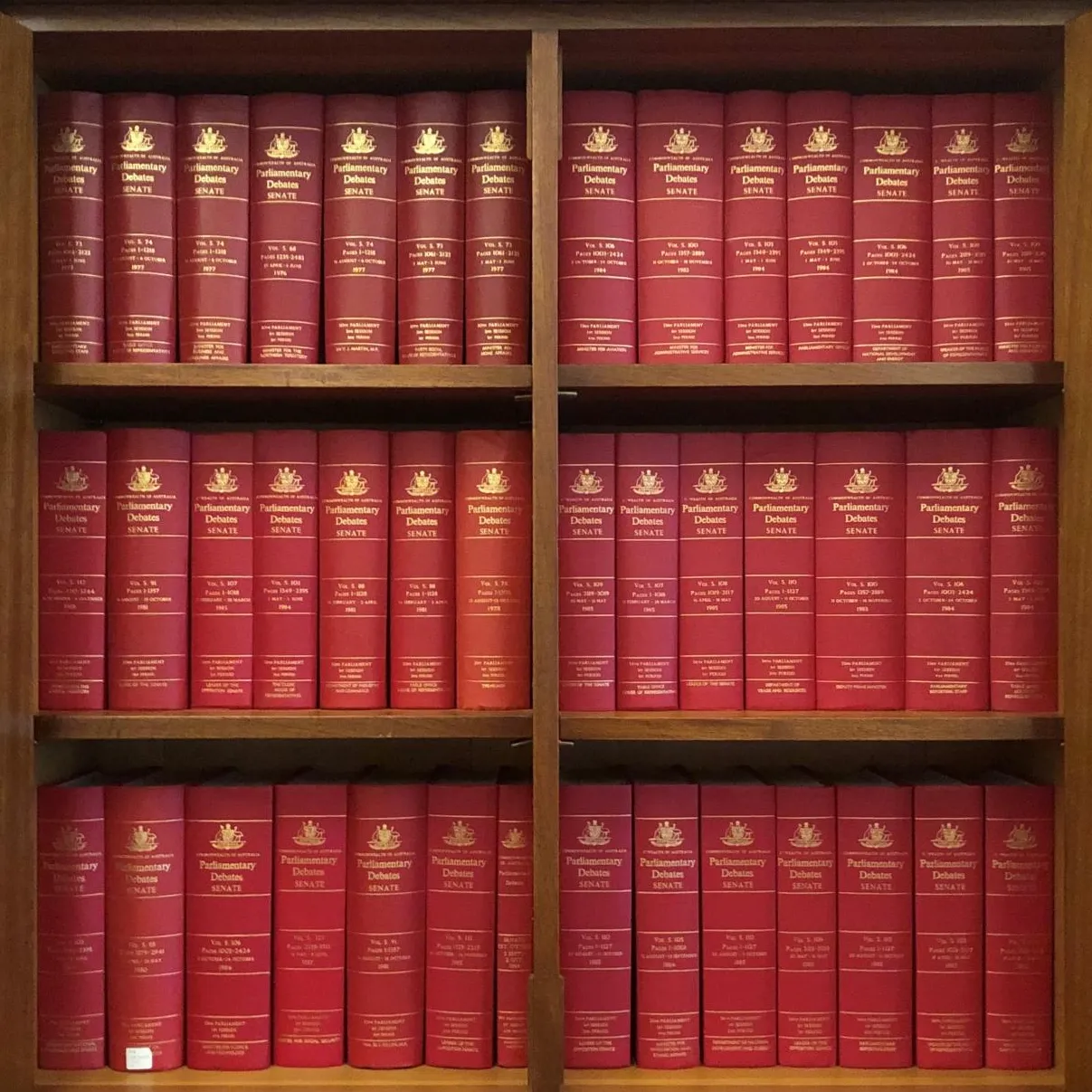

Hansard is testimony, in black and white, to our functioning federal parliamentary democracy - for all its strengths and weaknesses, its brilliance and tawdriness and its immense unending drama.

Since Federation in 1901 Hansard has recorded every audible word spoken in the House of Representatives and Senate, and their related committees.

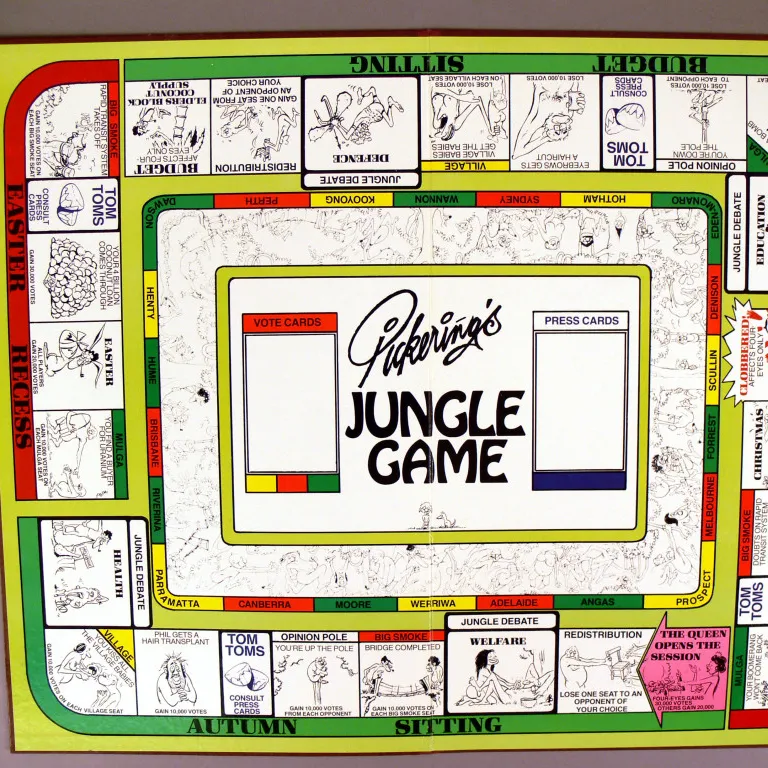

The nobility and foible, insult and praise, sorrow and elation in those hundreds of millions of words, are an earthy reminder that mortals, not gods, govern us - that it’s a Parliament of the people.

Hansard is our never-ending story. It chronicles more than merely a legislative journey from Federation. It enshrines our continental history, not least the unreconciled clash of the oldest continuing civilisation on earth with Empire, and the burning issues on which nationhood was founded but still struggles, 115 years later, to resolve.

By literally putting all of these words into your hands, for you to reinterpret and re-examine, HansART illustrates succinctly how Hansard not only belongs to those it records.

When the Duke of York opened this building – one of Australia’s most historically significant, 90 this year and now known as Old Parliament House – he observed how much had happened since Federation.

'What changes in the world!' he exclaimed.

But HansART’s themes – Indigenous Australians, women, immigration, refugees, environment, sport and culture and the Old House itself – demonstrate how consistently the same issues reverberate through our national discourse today.

In his 1971 maiden speech, Senator Neville Bonner, Australia's first Indigenous person to sit in the Commonwealth parliament, said, 'my people were shot, poisoned, hanged and broken in spirit . . . refugees in their own land. But that is history and we take care now of the present while, I should hope, we look to the future.'

Hansard had already charted debate around the 1967 referendum granting the Commonwealth power to legislate for Indigenous people.

Meanwhile, almost 50 years later, Linda Burney became the first Indigenous woman elected to the lower house. She opened her maiden speech in Wiradjuri: 'Ballumb Ambul Ngunawhal Ngambri yindamarra' (I pay respect to the ancient Ngunnawal and Ngambri).

In 1901 Sir John Forrest, supporting the Immigration Restriction Act, voiced concern Australia 'not be overrun with races whose sympathies, and manners, and customs, and religion are not as ours'.

95 years later a flame-haired Queensland Independent declared she wanted 'our immigration policy radically reviewed and that of multiculturalism abolished'.

The more things change... it’s all in Hansard.

In 1902 Senator Edward Pulsford volunteered how '...my heart and brain act together in antagonism to the principle of women’s suffrage', a worthy juxtaposition, when you flick through the continuing story of Hansard, to 2012's famous 'misogyny speech' of our first female prime minister, Julia Gillard.

'I will not be lectured about sexism and misogyny by this man.'

They are her words. But like the record of all the invective and praise, of united national moment and bitter partisanship, of the good, the bad and the ugly, in Hansard they become our words, our history.

Hansard is our story.