The Sydney Twelve — treason, conspiracy and conscription in Australia 1916

- DateFri, 18 Nov 2016

The ‘Sydney Twelve’ were members of an organisation known as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) who were arrested in Sydney on 23 September 1916 and charged with ‘treason felony’.

The charge was later changed to conspiracies relating to arson, perverting the course of justice and sedition.

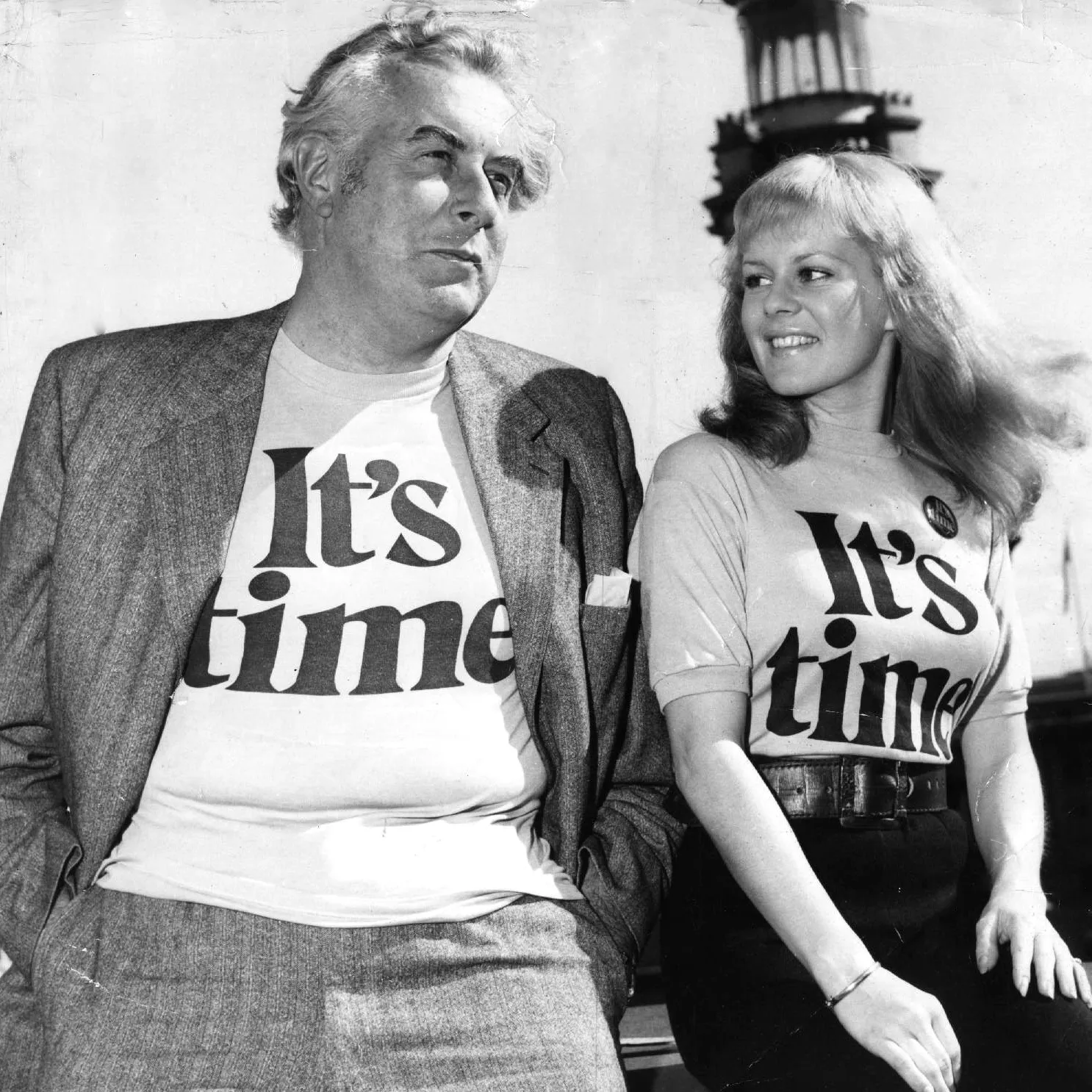

The timing of the arrests, during the campaign over the conscription plebiscite scheduled for 28 October, led many in the labour movement to view the charges with suspicion. The Hughes Labor government wanted a ‘Yes’ vote for conscription, and the IWW activists were proving effective in raising the question of opposition to the war as well as conscription.

This pitted the ‘Wobblies', as they were known, against the Labor government and the mainstream labour movement. The latter opposed conscription but not the war.

The Twelve were formally charged at Sydney Central Court on 3 October. The trial took place on 20 November. All were convicted. Seven received sentences of fifteen years’ gaol with hard labour, four were sentenced to ten years and one to five years.

The government and the media tried to link the Twelve to the murder of a policeman in the mining town of Tottenham, in central west NSW. The three men arrested for the murder were IWW supporters. Two were executed for the crime.

Influenced by socialism, anarchism and Marxism, the IWW was established in Chicago, USA, in 1906 . Perhaps its most famous member was Helen Keller, celebrated as the first deaf-blind woman to obtain a university degree. The IWW believed in ‘One Big Union’ rather than trade-based unions, and a General Strike as a way of overthrowing the capitalist class and replacing it with workers’ control of the means of production.

The IWW’s ideas soon took root in Australia. The defeat of the great strikes of the 1890s had led to faith in a parliamentary road to socialism. With the formation of a Labor Party and its election to government, that faith gave way to disenchantment and an extra-parliamentary militancy among a hard core of workers. In the years leading to war, wages were pegged and prices and unemployment rose. IWW membership was small, peaking at about 2000 in 1916, but its influence within the labour movement was greater. Its weekly paper Direct Action sold at least 15,000 copies and was read by many more. The Wobblies’ opposition to the war saw its influence grow among the small minority of Australians who opposed it.

The Labor government of Andrew Fisher declared that it would support Britain’s war effort ‘to our last man and shilling’ and brought in the War Precautions Act in October 1914, allowing for imprisonment of ‘disaffected and disloyal’ subjects.

A ‘recruitment’ poster produced by IWW leader Tom Barker in 1915 expressed the Wobblies’ position very well. It declared:

For expressing such a sentiment, Barker was arrested under the War Precautions Act but, on appeal, acquitted on a technicality. A repeat offence in March 1916, for ‘prejudicing recruitment’ in the IWW newspaper, Direct Action, led to a sentence of 12 months’ gaol with hard labour.

Following Barker’s gaoling, there were arson attacks on factories, warehouses, and business premises, including the Grace Brothers store in Sydney. One of the Twelve had declared publicly that 'for every day that Tom Barker is in gaol it will cost the capitalist class £10,000.'

The late historian, Ian Turner, in his book Sydney’s burning says that some of the Twelve ‘were incendiarists or would-be incendiarists’. Nonetheless, he concluded that they were framed up on the charges brought against them. He argues that it was the work of senior police and paid informers, including chief witness Harry Scully, who concocted evidence.

The Counter Espionage Bureau, the Chief Censor’s Office and the police were out to destroy the Wobblies, and toward the end of 1916 Hughes relied on the Liberals to secure passage of the Unlawful Associations Act. The Act resulted in scores of gaolings of IWW members for periods of up to six months, and deportations.

None of the Twelve served their full sentences. A campaign was mounted in their defence, with the support of some Labor parliamentarians. In 1918 the Labor Council of New South Wales commissioned a report, and a judicial enquiry into the case was conducted by Judge Street. Both revealed problems with the case, though Street found no new evidence warranting the men’s release or a retrial.

After the Storey Labor government was elected in New South Wales in 1920, Judge Ewing was appointed to inquire into the trial and sentencing. The judge rejected any suggestion that the men had been framed but recommended their release, finding that six were not ‘justly or rightly’ convicted of sedition. All were released later that year.