The 1966 Wave Hill walk-off

The Gurindji strike and its legacy explained.

First Nations readers are advised that this article contains names and images of people who have died.

Wave Hill Station, commonly known as Wave Hill, is a pastoral lease operating as a cattle station about 600 kilometres south of Darwin in the Victoria River District of the Northern Territory. It is where the Wave Hill walk-off, or Gurindji strike, took place in 1966.

What was the Wave Hill walk-off?

On 23 August 1966, Gurindji man Vincent Lingiari led a walk-off from Wave Hill of 200 Gurindji workers and their families. The walk-off was in protest of poor work and pay conditions at Wave Hill under the station owners, international meat-packing company, Vestey Brothers, as well as a call for land rights.

Throughout the remainder of 1966, the striking workers held consultations with other Gurindji members, members of the North Australian Workers Union, and the Northern Territory Council for Aboriginal Rights. However, no agreement was reached with Vestey Brothers, and the workers did not return to work at Wave Hill.

A short film about Wave Hill striker Jimmy Wave Hill and his experience of the Wave Hill walk-off in 1966. Film by Brenda L Croft and James Falconer Marshall.

What led to the Wave Hill walk-off?

The Gurindji had lived on their homelands in the Victoria River area of the Northern Territory for tens of thousands of years. In the late 1800s, the government granted a large amount of this land to pastoralist Nathaniel Buchanan, who brought in thousands of cattle and established Wave Hill Station.

In 1914, Vestey Brothers purchased Wave Hill from the Buchanan family, employing local Gurindji people to work on the property.

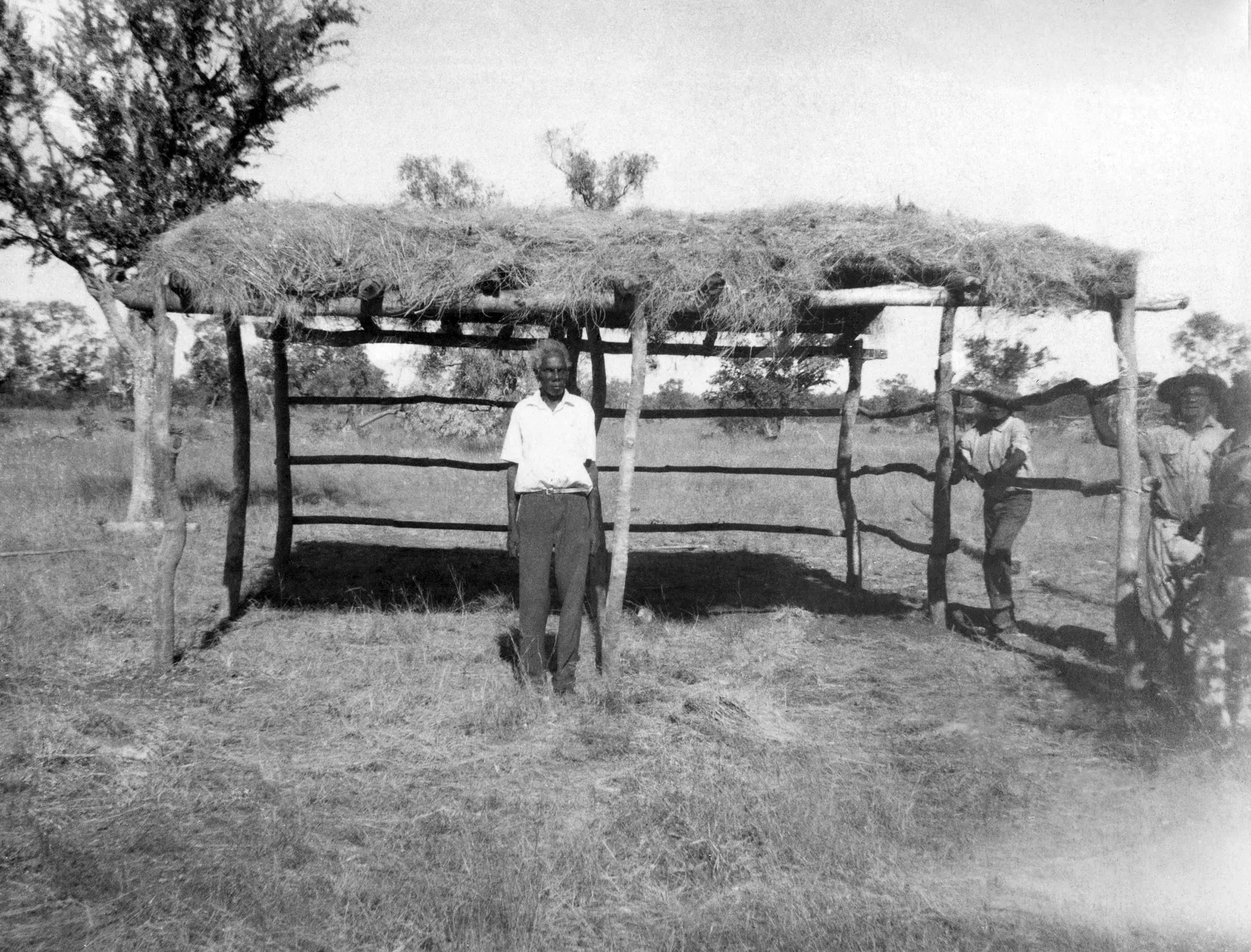

The Gurindji workers lived in basic corrugated iron structures that didn't have floors or lights. There was no sanitation, and they didn't have easy access to safe drinking water. They were paid less than minimum wage and sometimes only received rations (food, tea, tobacco) instead of wages.

In 2006, former Wave Hill stockman Mr Jampijinpa, who was part of the walk-off, recalled: 'We were treated like dogs. We were lucky to get paid the 50 quid a month we were due, and we lived in humpies you had to crawl in and out of on your knees … There was no running water, the food was bad ...'

This situation wasn't unique to Wave Hill. By the 1960s, tensions between pastoralists and First Nations workers across the Northern Territory were high, workers were increasingly demanding better pay and conditions. In 1965, plans were in place to change the law, making it illegal for First Nations people to be paid less than white workers. However, pastoralists opposed this and convinced the government to delay the change by three years.

The delayed law change, along with the poor work and pay conditions all contributed to the Wave Hill walk-off.

What happened after the Wave Hill walk-off?

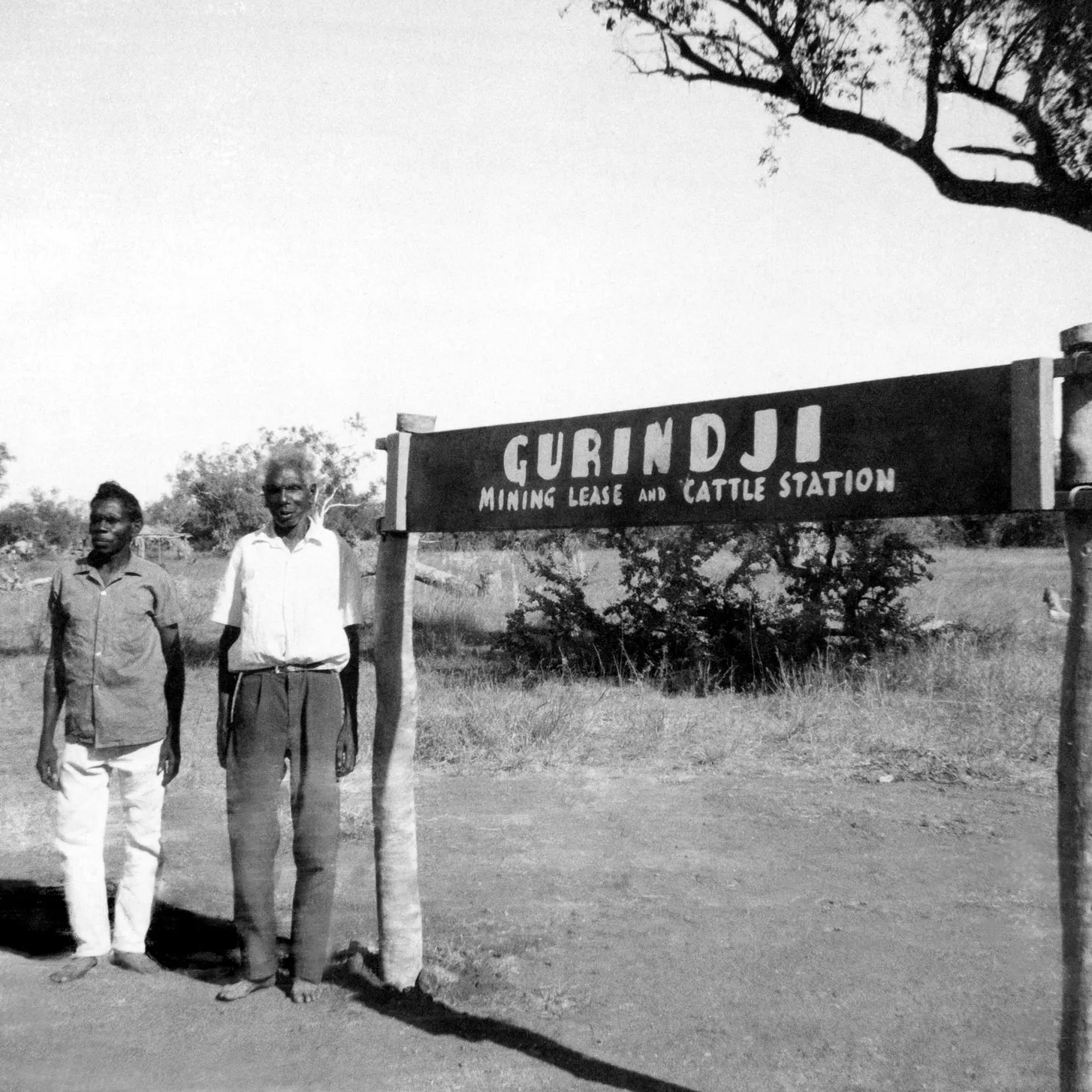

In 1967, with no resolution between the workers and Vestey Brothers, the Gurindji set up camp about 20 kilometres away at Daguragu (also known as Wattie Creek). They enlisted the help of a key supporter of their cause, author Frank Hardy, to make a sign saying 'Gurindji', which they erected on the land. It soon became clear that although the walk-off had begun as a claim for fairer working conditions, it was about the bigger issue of land rights.

- Vincent Lingiari, 1966

Vincent Lingiari at his house, Gurindji Camp, Wattie Creek.

Photograph NAA: F1, 1968/2735N

The Gurindji petitioned the government requesting a portion of their land be returned to them to run as a mining lease and cattle station. This was rejected. Over the next nine years, the Gurindji continued to send petitions and requests to the government, without success. Unions and many others supported them during their long strike.

The land hand back

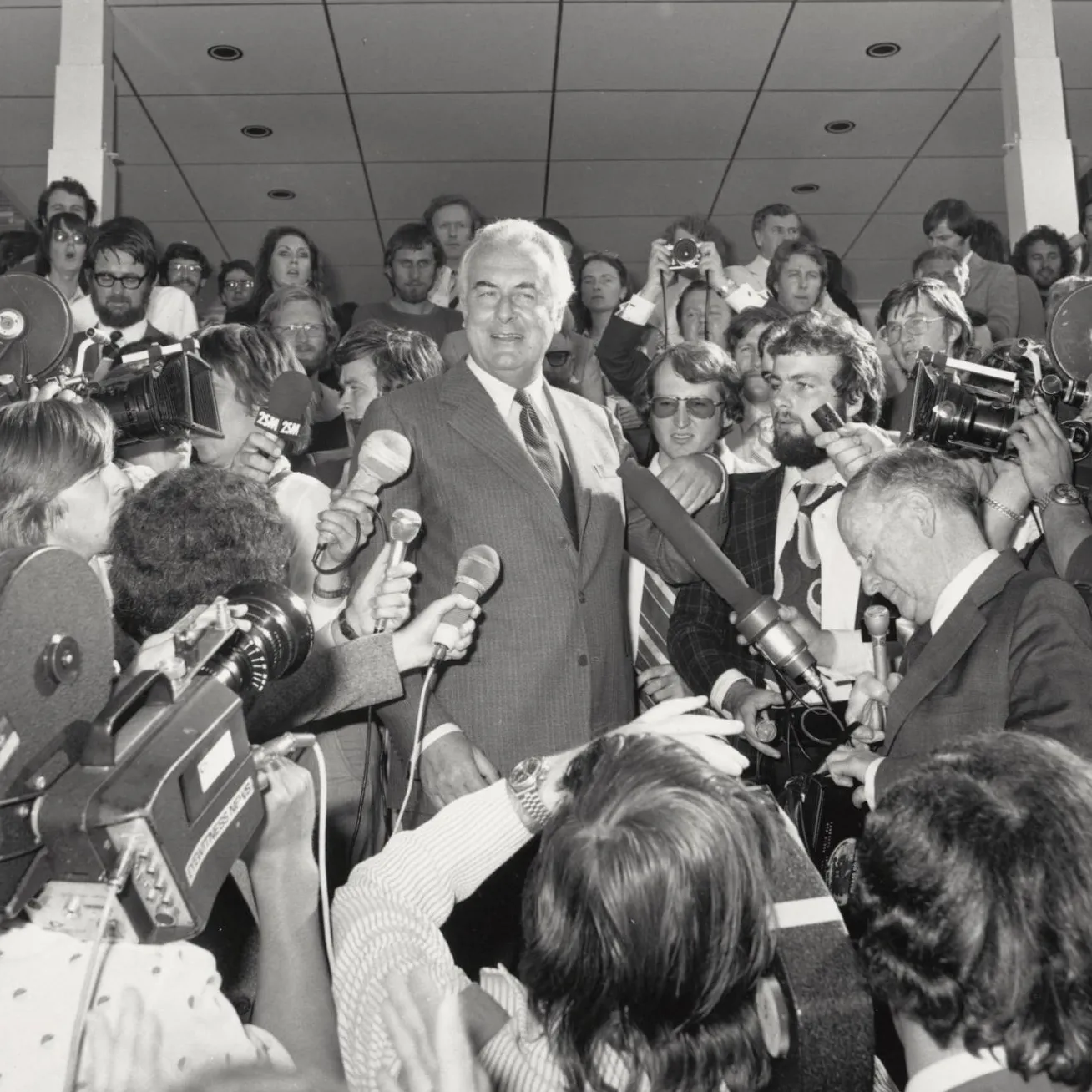

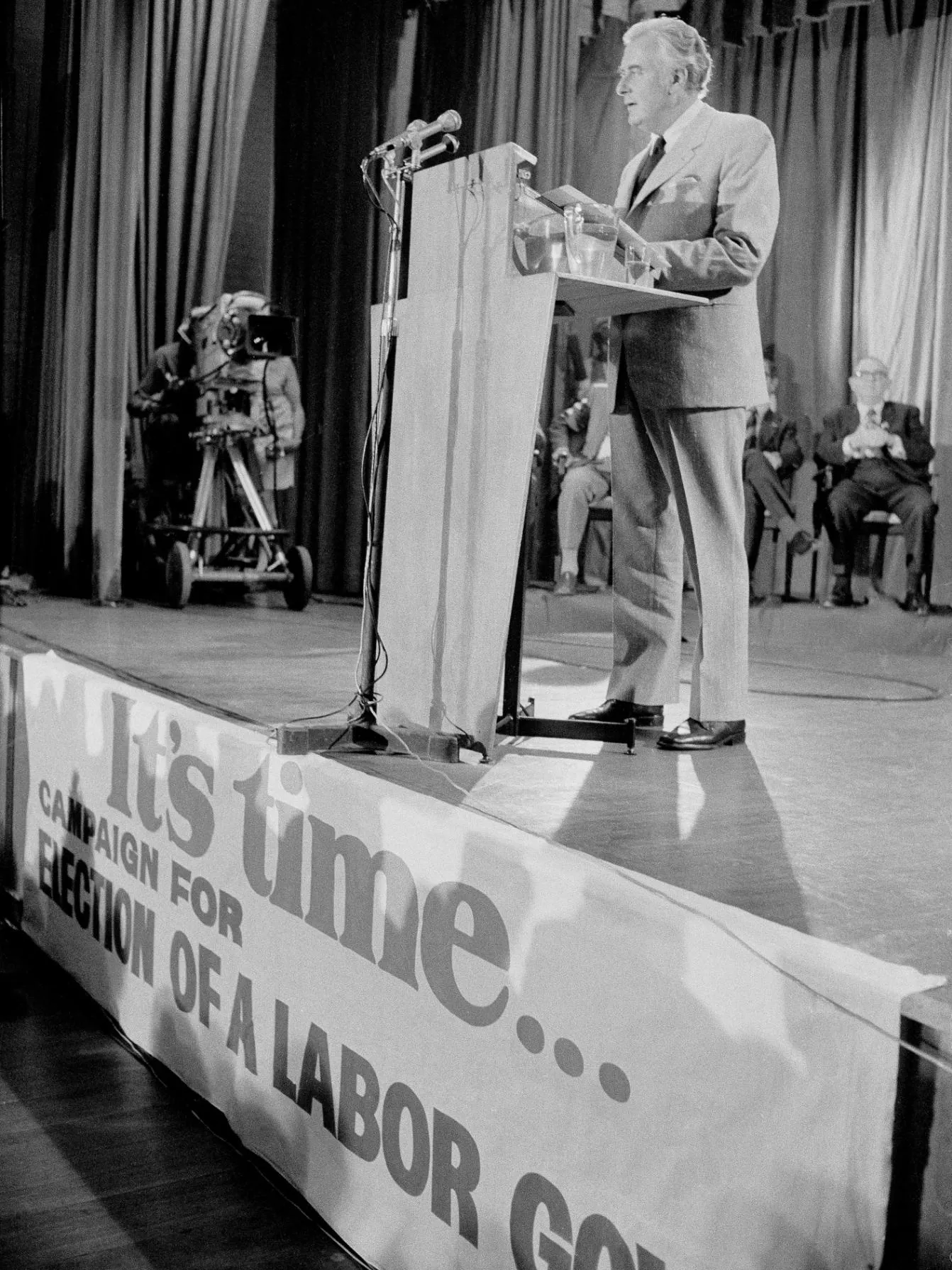

The election of the Whitlam government in 1972 brought hope to the Gurindji people. In November 1972 during his election speech at Blacktown Town Hall, Gough Whitlam pledged that his government, if elected, would 'legislate to give Aborigines land rights'.

In 1973 two new leases for Wave Hill were issued to replace the original lease: one to Vestey Brothers and one to the Murramulla Gurindji Company.

In August 1975 Prime Minister Gough Whitlam travelled to Daguragu and ceremonially poured a handful of Gurindji soil into the hand of Vincent Lingiari. Whitlam said: 'Vincent Lingiari, I solemnly hand to you these deeds as proof, in Australian law, that these lands belong to the Gurindji people, and I put into your hands part of the earth as a sign that this land will be the possession of you and your children forever.'

A short film about Gurindji man John Leemans reflecting on being at the Gurindji land handover ceremony in 1975 and its legacy. Film by Brenda L Croft and James Falconer Marshall.

Legacy of the Wave Hill walk-off

The Wave Hill walk-off was an important event in Australia's land rights movement and helped pave the way for the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. This Act was the first law recognising First Nations peoples claim for land rights.

In 1986, the Gurindji gained freehold title to Daguragu. There continues to be a Gurindji community living at Daguragu today.

In Canberra, Vincent Lingiari is remembered on a memorial in Reconciliation Place and the walk-off is commemorated and celebrated in culture, art and music.

A short film of Gurindji woman Leah Leemans talking about the importance of the 1966 Wave Hill walk-off. Film by Brenda L Croft and James Falconer Marshall.

The Gurindji freedom banners

The Gurindji freedom banners are a collection of 10 appliqué and hand-painted banners created in 2000 by the Gurindji to share their version of the story of the Wave Hill walk-off.

The Freedom Day Festival

The Gurindji Freedom Day Festival is an annual festival commemorating the Wave Hill walk-off and contribution made by the Gurindji, Mudbara and Walpiri families to Australia's land rights history.

Wave Hill walk-off in music

Former Northern Territory Administrator Ted Egan wrote the song The Gurindji Blues in 1969. It features performances by Vincent Lingiari and Yolngu spokesman, Galarrwuy Yunupingu. In 1991, Kev Carmody and Paul Kelly composed a song commemorating the walk-off, From little things, big things grow.

What is a pastoralist?

A pastoralist is similar to a farmer, but they focus on raising livestock like cattle or sheep on their land for their livelihood, rather than growing crops.

What is a pastoral lease?

It is a lease issued for Crown land on which the person or company who has been granted the lease must raise livestock for their livelihood. It is for a specific time and there are conditions.