How elections are called in Australia

The start of the election process explained.

ln our representative democracy, all citizens aged 18 years and over vote for people in elections to represent them in Australian Parliament to make laws and decisions on their behalf. There are three levels of government in Australia – federal, state or territory, and local – and voters elect representatives to each of these levels.

The last sitting of the House of Representatives at Old Parliament House on 3 June 1988.

Photograph by Robert McFarlane, Department of the House of Representatives

Who makes the election rules?

Federal elections in Australia are governed in accordance with the Australian Constitution and the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) organises and runs federal elections, ensuring they are fair and legal.

Each state and territory has its own electoral laws for state and local elections. Although the process is generally the same, there are differences. These include funding, campaigning, and systems to choose parliamentary members. For example, New South Wales has rules on who can make donations to parties and candidates, and in the Australian Capital Territory, canvassing for votes is illegal within 100 metres of a polling place.

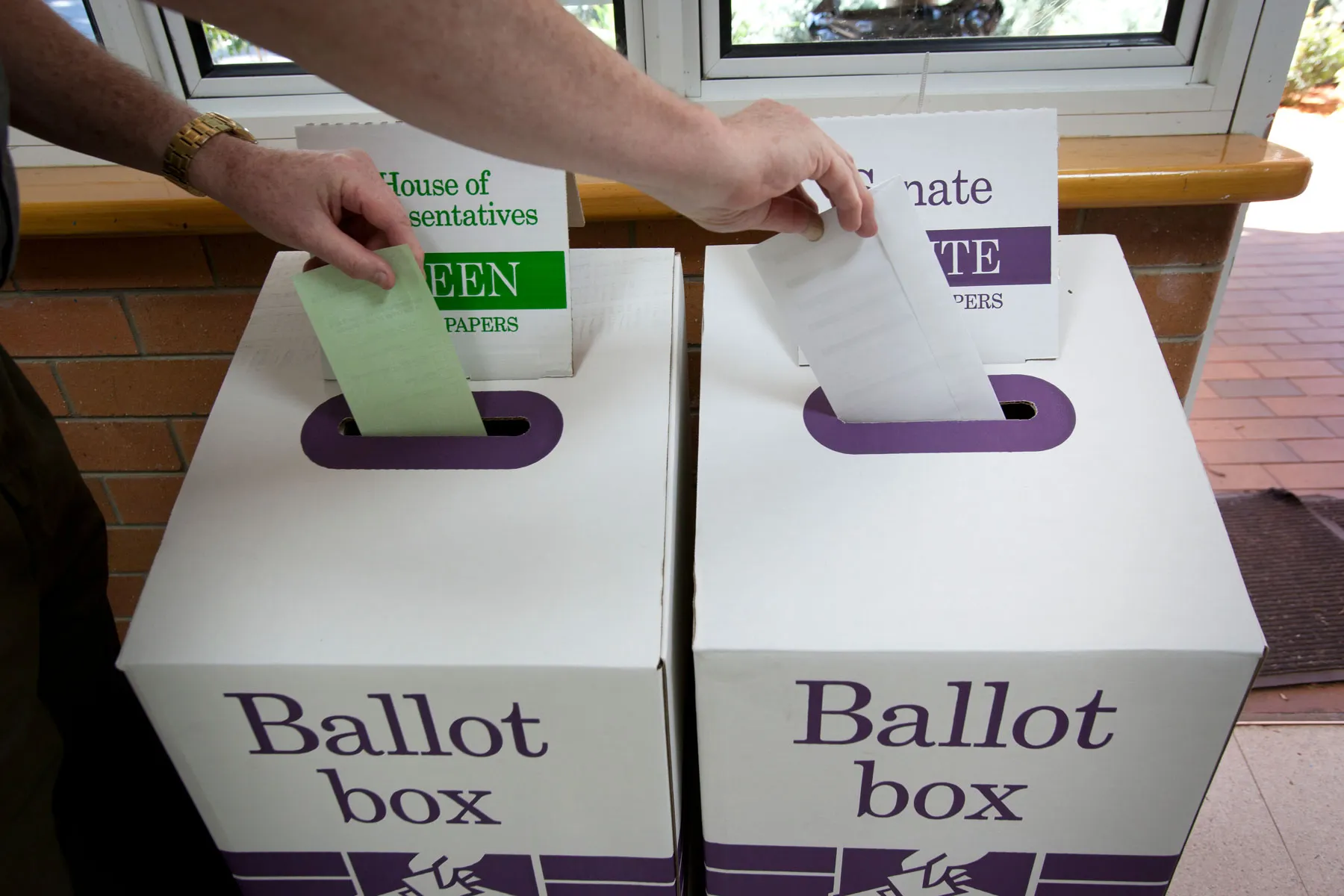

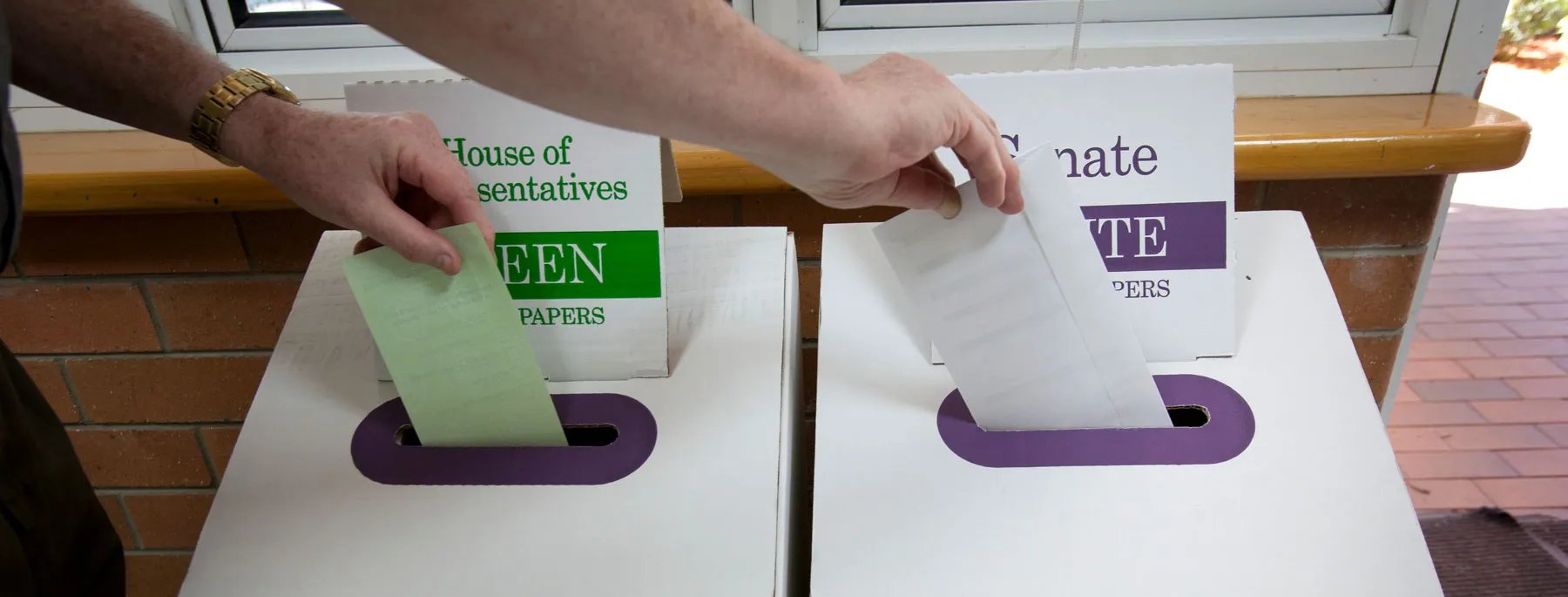

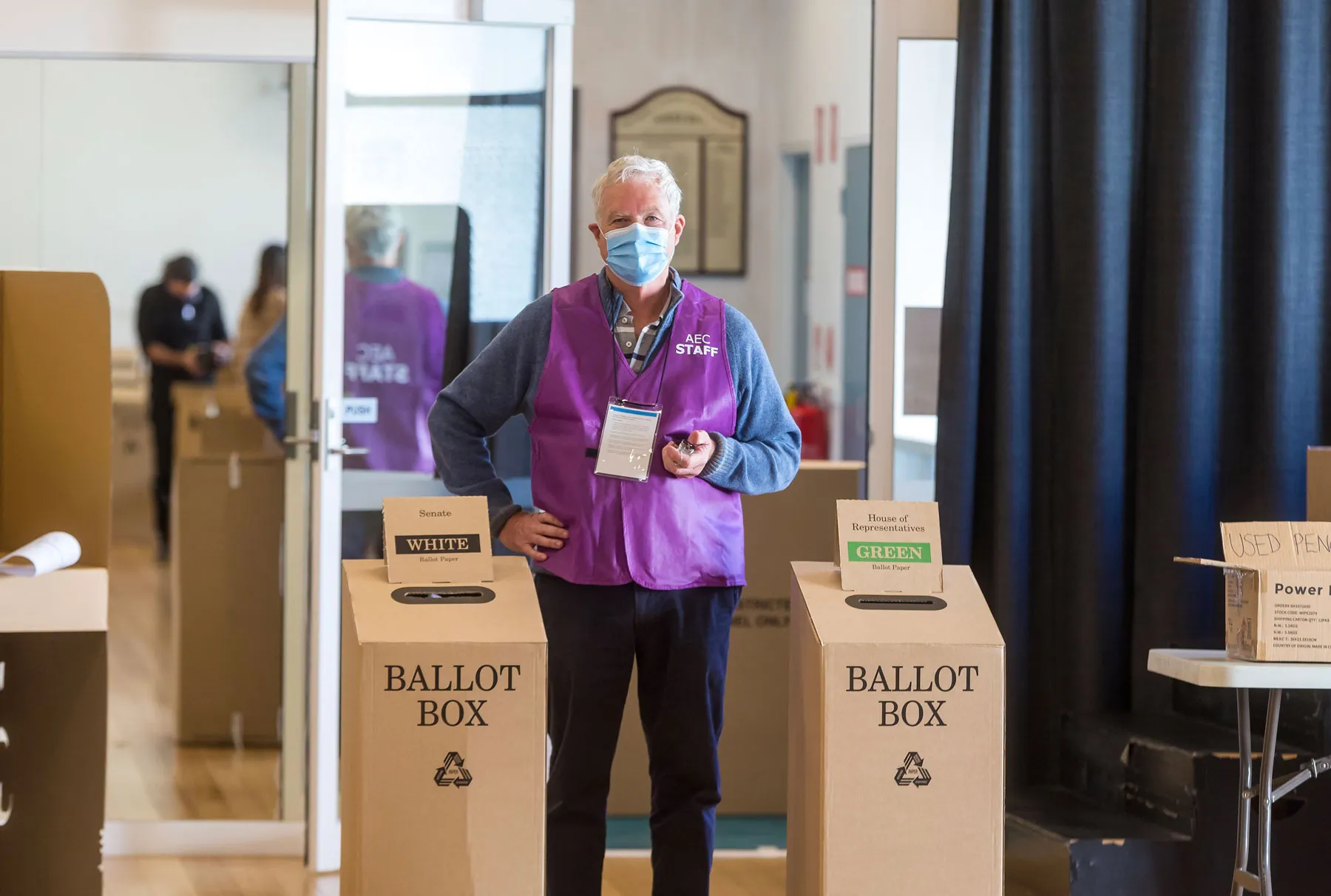

Image 1: A polling place for the 2022 federal election.

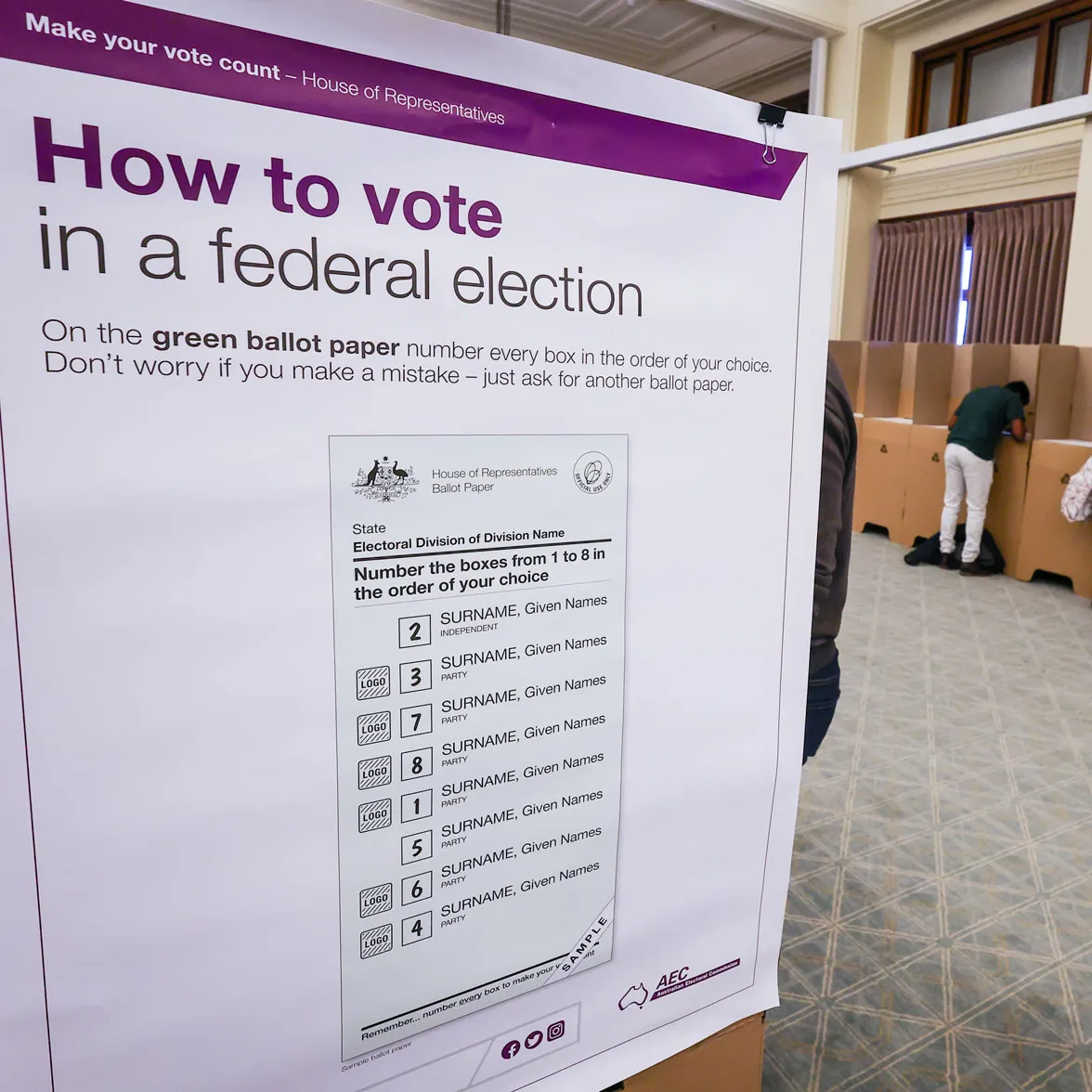

Image 2: Australian Electoral Commission federal election voting instructions for voters voting at Old Parliament House.

Image 3: Australian Electoral Commission officials counting votes at Old Parliament House watched by scrutineers.

Photography courtesy of the Australian Electoral Commission

When are elections held in Australia?

All states and territories have terms of four years, with a fixed election date. For instance, Victorian elections are held on the last Saturday in November every four years.

The Commonwealth has a three-year term for the House of Representatives and a six-year term for the Senate. The term of the House of Representatives expires three years after it first meets, so election dates vary.

Who can call an election?

The governor-general has the power to start the process for a federal election. This occurs when the three-year term of the House of Representatives expires, or if the governor-general dissolves the House of Representatives early on the advice of the government.

The date is determined by the governor-general, as requested by the government, and typically includes an election for all the House of Representatives and half the Senate.

When a prime minister requests an election, the governor-general can refuse.

As of 2025, no governor-general has refused to call an election when a prime minister has requested it.

The authority to hold an election is in the form of a writ issued by the governor-general. In the case of a by-election, the writ is issued by the Speaker of the House of Representatives.

What is a writ?

In an election, a writ is the legal document authorising an election to be held to choose a new parliament. It specifies the election details, including when electoral rolls close, the deadline for nominations and polling date.

Eight writs are issued for a federal election, one for each state and territory. The writs must be issued within 10 days of the dissolution or expiry of the House of Representatives.

What are the key dates in an election?

After the writs are issued, you have seven days to enrol to vote if you're eligible, such as if you've turned 18 since the last election.

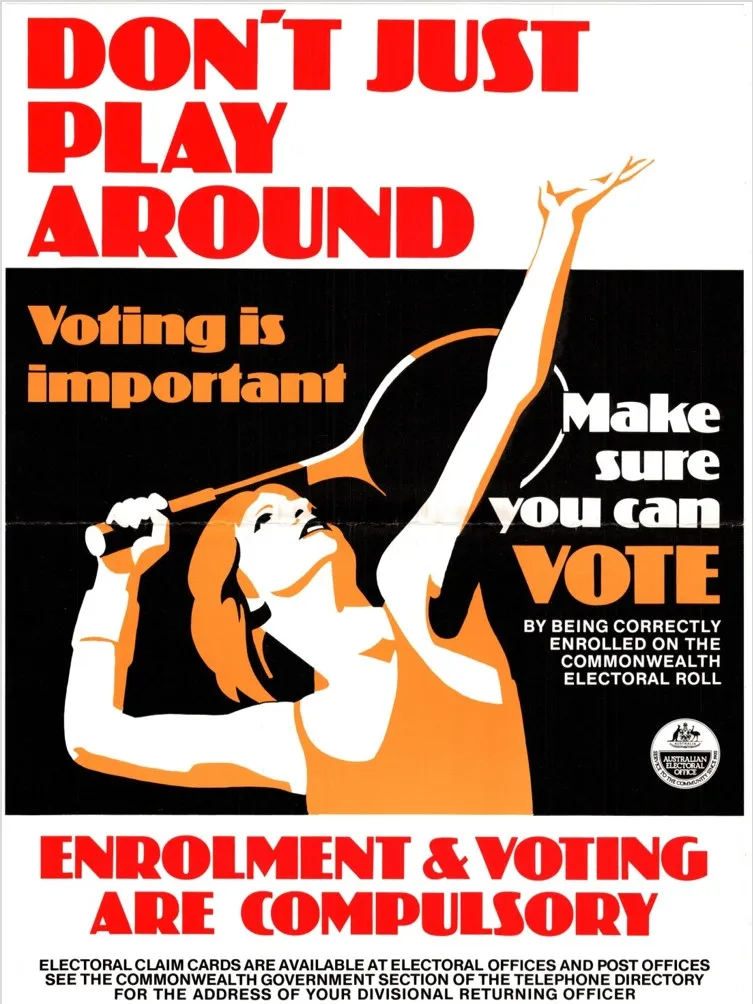

Historical enrol to vote poster about the importance of voting and not just 'playing around'. Courtesy of the Australian Electoral Commission

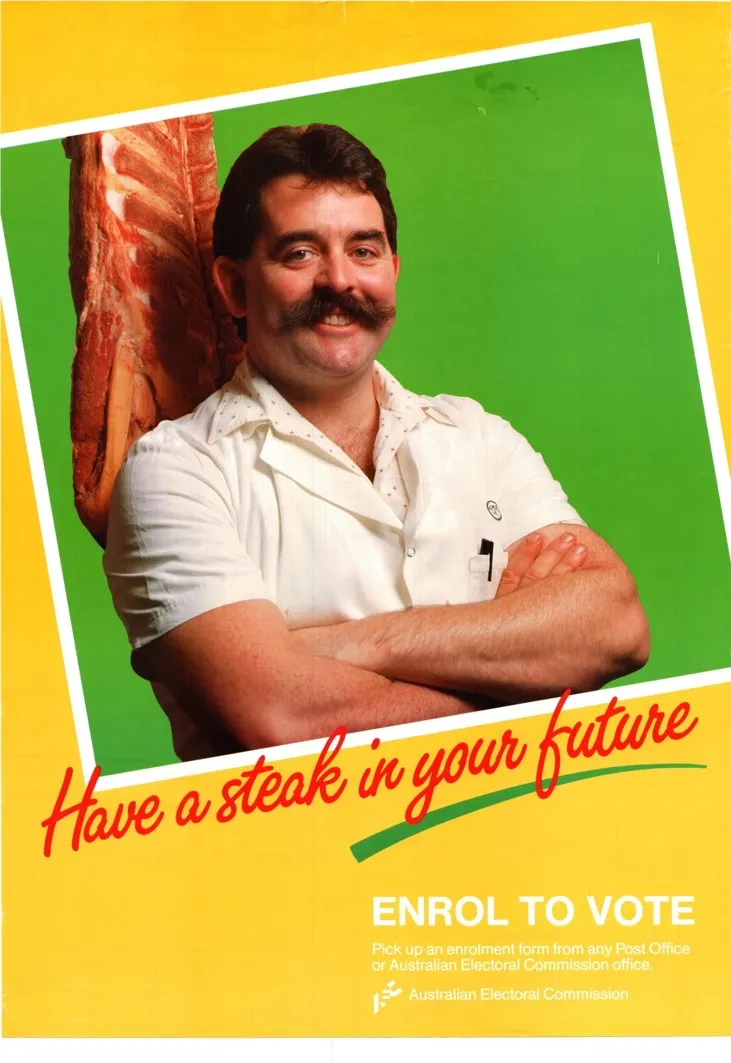

Historical enrol to vote poster about having a 'steak' in your future. Courtesy of the Australian Electoral Commission

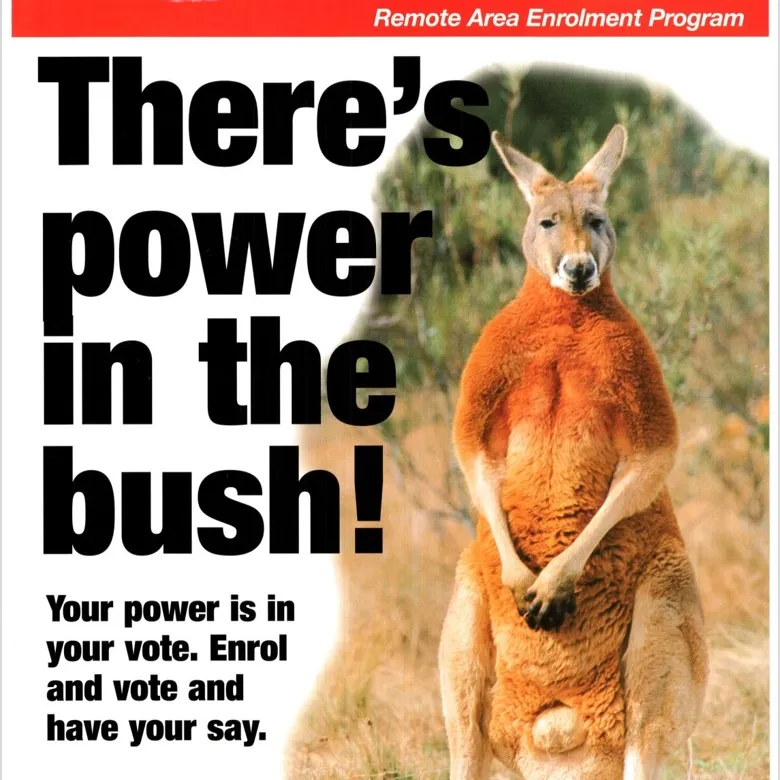

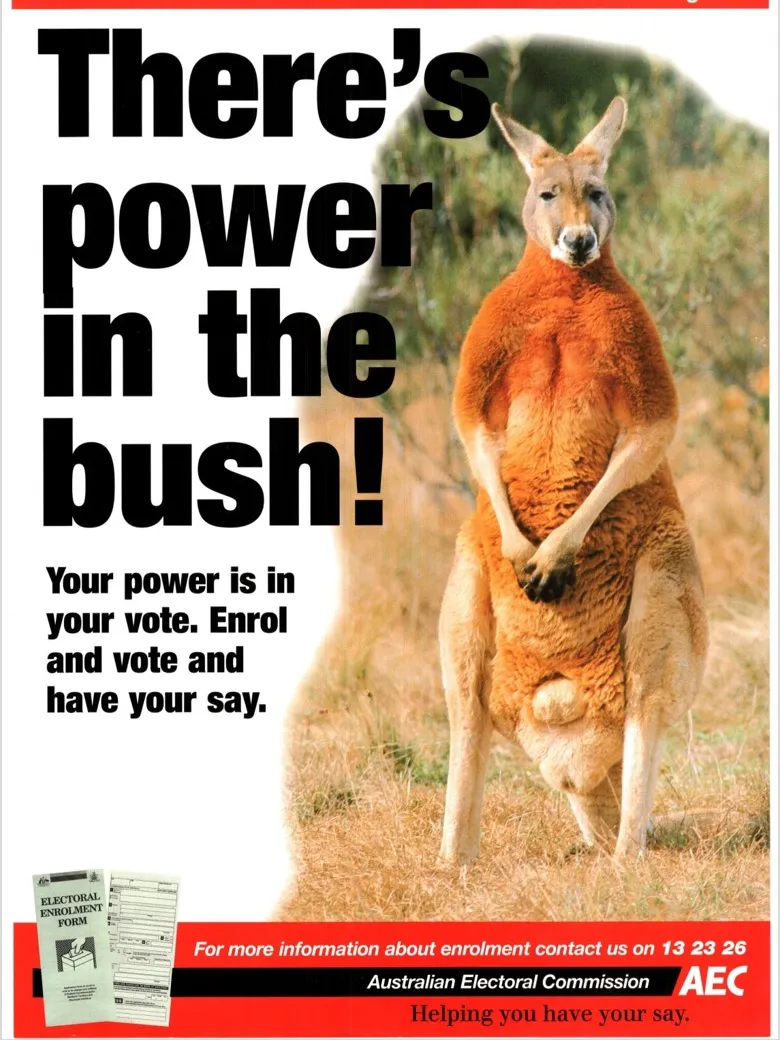

Historical remote area enrol to vote poster calling on the 'power in the bush'. Courtesy of the Australian Electoral Commission

The deadline for nominations is not less than 10 days nor more than 27 days after the writs are issued. Most parties choose candidates before the election is called and nominate them all at once. However, in the 2024 local government elections, the New South Wales Liberal Party missed the nomination deadline for more than 100 of its candidates and they were unable to run.

The polling date – a Saturday – is not less than 33 days nor more than 58 days, i.e. five to eight weeks, after the writs are issued.

An example of timing from the 2022 federal election:

| Year | Issue of writ | Close of rolls Seven days after writ issued | Close of nominations Not less than 10 days nor more than 27 days after writ issued | Polling day Not less than 33 days nor more than 58 days after writ issued |

| 2022 | 11 April 2022 | 18 April 2022 | 21 April 2022 | 21 May 2022 |

What is a by-election?

A by-election is held when there is a vacancy in the House of Representatives due to death, resignation, absence without leave, expulsion, disqualification or ineligibility. In this instance, a writ for the by-election is issued by the Speaker to elect a new member to the House of Representatives.