1967: Indigenous affairs

Stand up and be counted

Date

27 May 1967

Question

DO YOU APPROVE the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled— "An Act to alter the Constitution so as to omit certain words relating to the People of the Aboriginal Race in any State and so that Aboriginals are to be counted in reckoning the Population"?

Result

An overwhelming majority of Australians voted YES and the Constitution was changed.

NSW

Yes: 1,949,036 (91.46%), No: 182,010 (8.54%)

VIC

Yes: 1,525,026 (94.68%), No: 85,611 (5.32%)

QLD

Yes: 748,612 (89.21%), No: 90,587 (10.79%)

WA

Yes: 319, 823 (80.95%), No: 75, 282 (19.05%)

SA

Yes: 473,440 (86.26%), No: 75, 383 (13.74%)

TAS

Yes: 167,176 (90.21%), NoL 18,134 (9.79%)

Total

Yes: 5,183,113 (90.77%), No: 527,007 (9.23%)

A May Day float from the Queensland branch of the Australian Builders Labourers’ Federation shows support of the Yes campaign in Brisbane, 1967.

University of Queensland Library F3400 Folder 12, item 2, Fryer Library

Until 1967, responsibility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs had fallen to the states. After a long campaign led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activists, Australians were asked to vote on a proposed change to the Constitution: removing the words that prohibited the federal government from making laws concerning Indigenous people. The referendum also proposed changing the parts of the constitution that stopped Indigenous people being counted when calculating things like how many members of parliament each state had, or payments to the states based on population.

Since the colonisation of Australia in 1788, colonial and state governments had been responsible for Indigenous affairs, leaving them with the power to create discriminatory laws that dispossessed and oppressed communities. Being left out of the census also meant Indigenous people weren’t counted when drawing boundaries for parliamentary seats, leaving them further disenfranchised.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people had always protested the injustices they experienced. Major actions included The Day of Mourning, organised by William Ferguson and Jack Patten in 1938, the Yirrkala Bark Petitions of 1963, Charles Perkins' 1965 Freedom Ride and the Wave Hill walkout of 1966, led by Vincent Lingiari. These powerful statements helped change public opinion and bring attention to discrimination against First Nations people. Other activists for change included Faith Bandler, a South Sea Islander woman who firmly believed in equality for First Nations people.

Bandler's organisation, the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAASTI) collected 100,000 signatures on a petition calling for change. It was presented to Prime Minister Robert Menzies in 1965. The exhaustive work by all these activists convinced increasing numbers of Australians to support a constitutional amendment. Their persistent lobbying paid off and the Holt government called a referendum in early 1967.

- Joyce Clague, referendum and political activist

Unusually for a referendum, there was no official 'no' case produced due to the overwhelming support in parliament. The 'yes' campaign was fought mostly on citizen rights, with campaign materials created by FCAATSI imploring Australians to 'right wrongs, write YES'.

A staggering 90.77% of voters agreed to the amendment. A second proposal, about the size of parliament was rejected by almost 60% of voters. Interestingly, it was this second question that dominated media commentary at the time. The muted media opposition to the Indigenous affairs proposal is possibly explained by both the lack of a formal 'no' campaign and public sense of a need to 'right wrongs' with an overdue reform.

For First Nations people and 'yes' campaigners, the resounding result was celebrated as a national victory. To this day the 1967 referendum is recognised as a landmark moment – a hugely significant symbol for Indigenous Australians of survival, power and being heard.

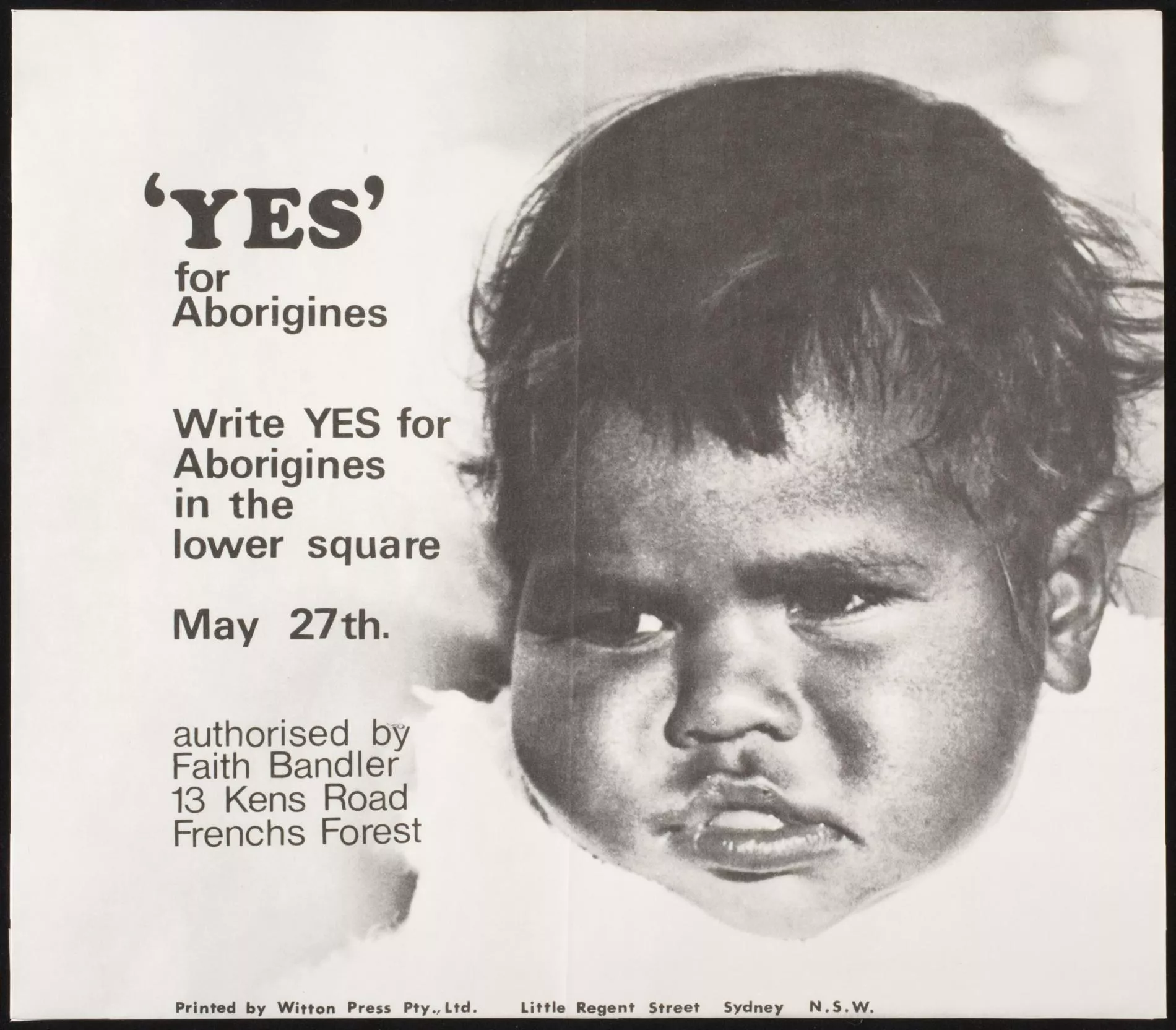

The iconic ‘Yes’ campaign poster from the referendum features a young First Nations girl, Janelle Marshall, and authorisation from activist Faith Bandler, 1967.

National Museum of Australia 2018.0008.0002

- Justin Mohamed, Ambassador for First Nations people

Extract from the official YES case

'Our personal sense of justice, our common sense, and our international reputation in a world in which racial issues are being highlighted every day, require that we get rid of this outmoded provision.

...for some years now Aboriginals have been entitled to enrol for, and vote at, Federal Elections. Yet Section 127 prevents them from being reckoned as "people" for the purpose of calculating our population, even for electoral purposes.

The simple truth is that Section 127 is completely out of harmony with our national attitudes and modern thinking. It has no place in our Constitution in this age.

All political parties represented in the Commonwealth Parliament support these proposals. The legislation proposing these Constitutional amendments was, in fact, adopted unanimously in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. We have yet to learn of any opposition being voiced to them from any quarter.'

Source: Official referendum pamphlet, 1967

The NO case

No formal NO case existed.

Did you know...?

- The record 'yes' result is the largest for an Australian referendum by a wide margin.

- This wasn't the first referendum on Indigenous affairs. In 1944, the power to make laws for Aboriginal people was one of 14 new powers put to referendum, but the entire suite of powers was voted on all at once, and rejected.

- This is the only constitutional change that resulted in a section of the Constitution being entirely deleted from the text. Section 127 of the Constitution is now blank.