Election campaigning in Australia

How parties and candidates campaign for your vote.

When an election is called, aspiring politicians and incumbents looking for re-election start the election campaign process, hoping to win your vote.

Millions of dollars are spent and every medium is employed to advertise and promote their policies to convince you to vote for them. Advertising methods include TV, radio, online, social media, letterbox drops, text messages, phone calls, community meet and greets, televised debates, polls and merchandise (think badges, T-shirts and caps). Australia is small fry compared to other countries, in the US, major political parties spend hundreds of millions of dollars on campaigns.

Malcolm Fraser at the launch of the Liberal Party's election campaign at Dallas Brooks Hall, 1975. Photograph NAA: A6180, 1/12/75/13

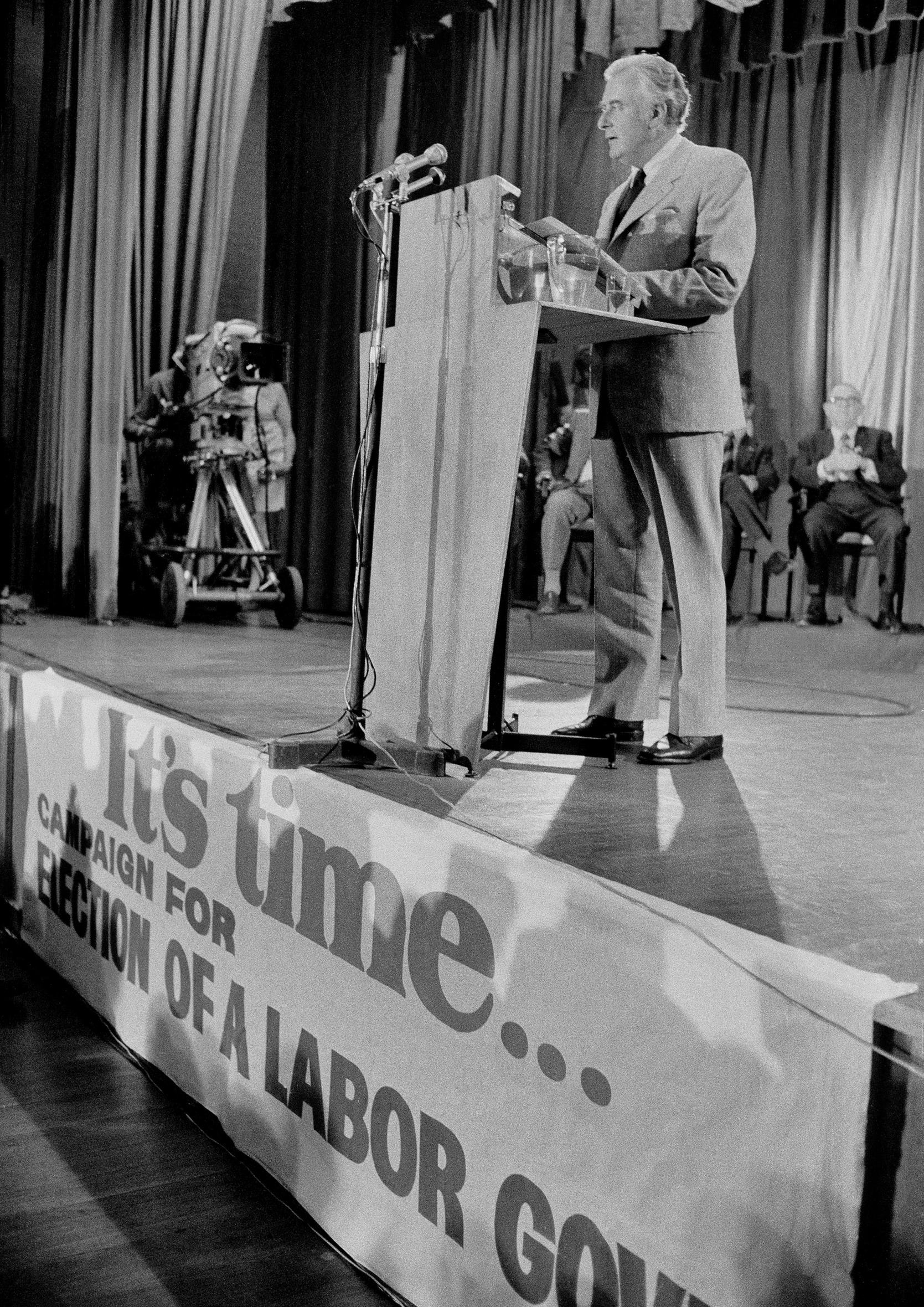

Bob Hawke speaking at an Australian Labor Party election rally in Perth, 1972. Photograph NAA: A6180, 5/12/72/9

Because it is compulsory for Australian citizens aged 18 years or older to vote, the campaign messaging in Australia is directed towards influencing how you cast your vote. In countries where voting is voluntary, like the US, campaign messaging often aims to persuade people to simply go out and vote.

Are there rules around election campaigning?

Yes! Federal elections are governed in accordance with the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 and the Australian Constitution. This includes the deadline for candidate nominations as well as rules around election communication and advertising. Each state and territory has its own electoral laws for state and local elections, although the process is generally the same.

Campaign advertising

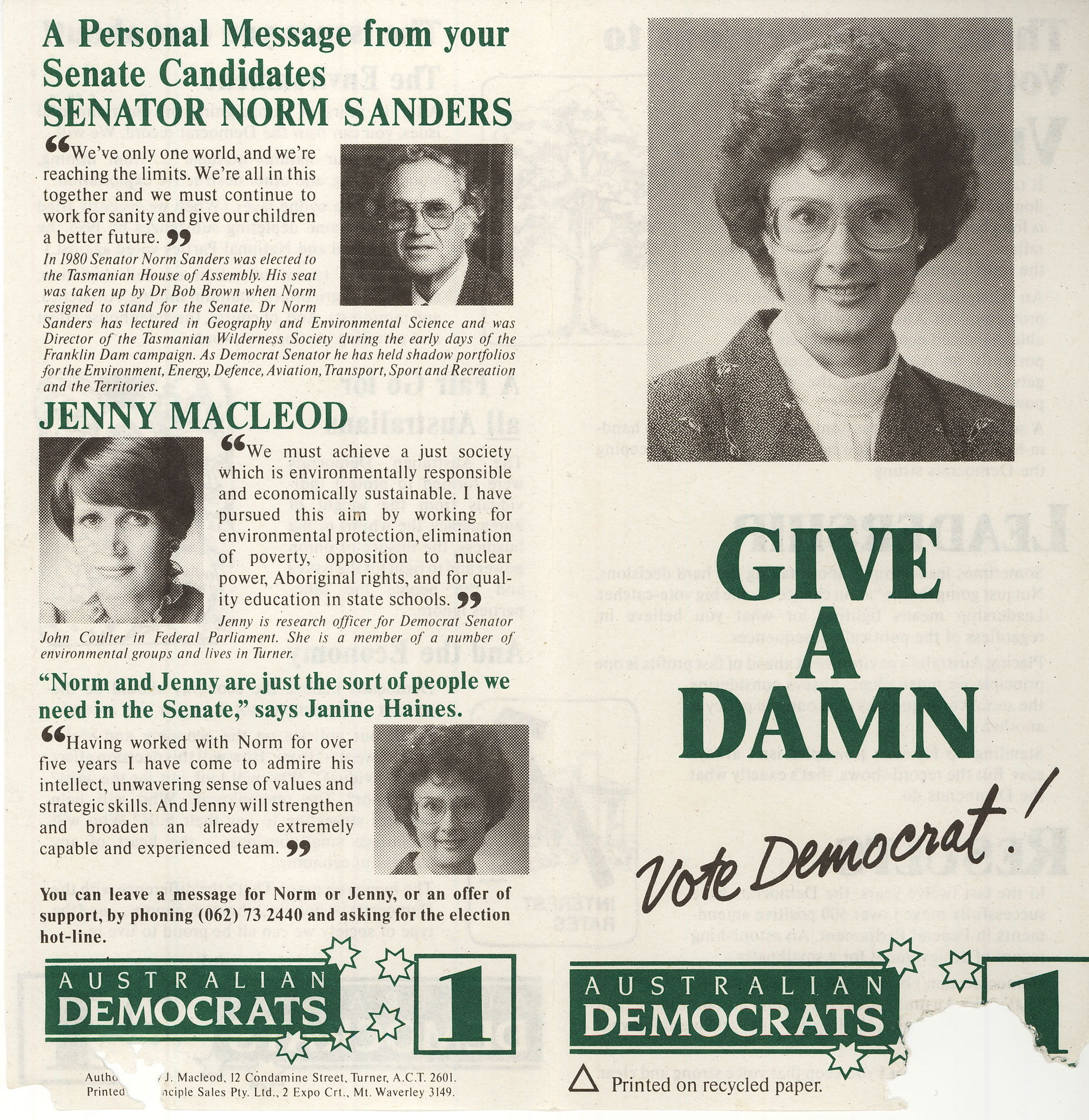

During an election campaign, you'll likely come across political advertising in some form every day. The rules don't limit how often and where ads can appear, but every official election advertisement or communication must be authorised, so you know the source. There may be legal consequences if it is not authorised.

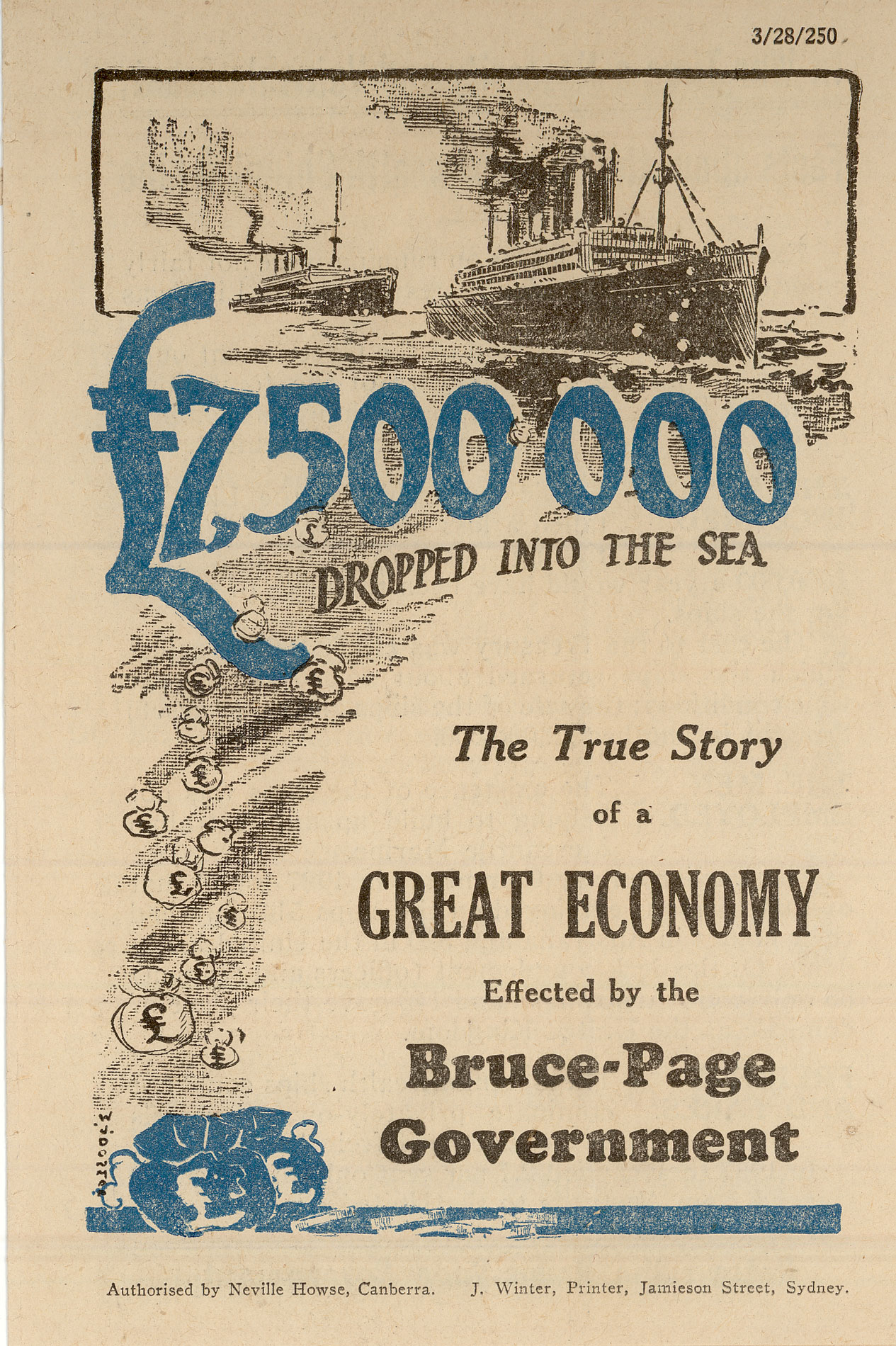

Nationalist Party leaflet, 1928. Museum of Australian Democracy collection

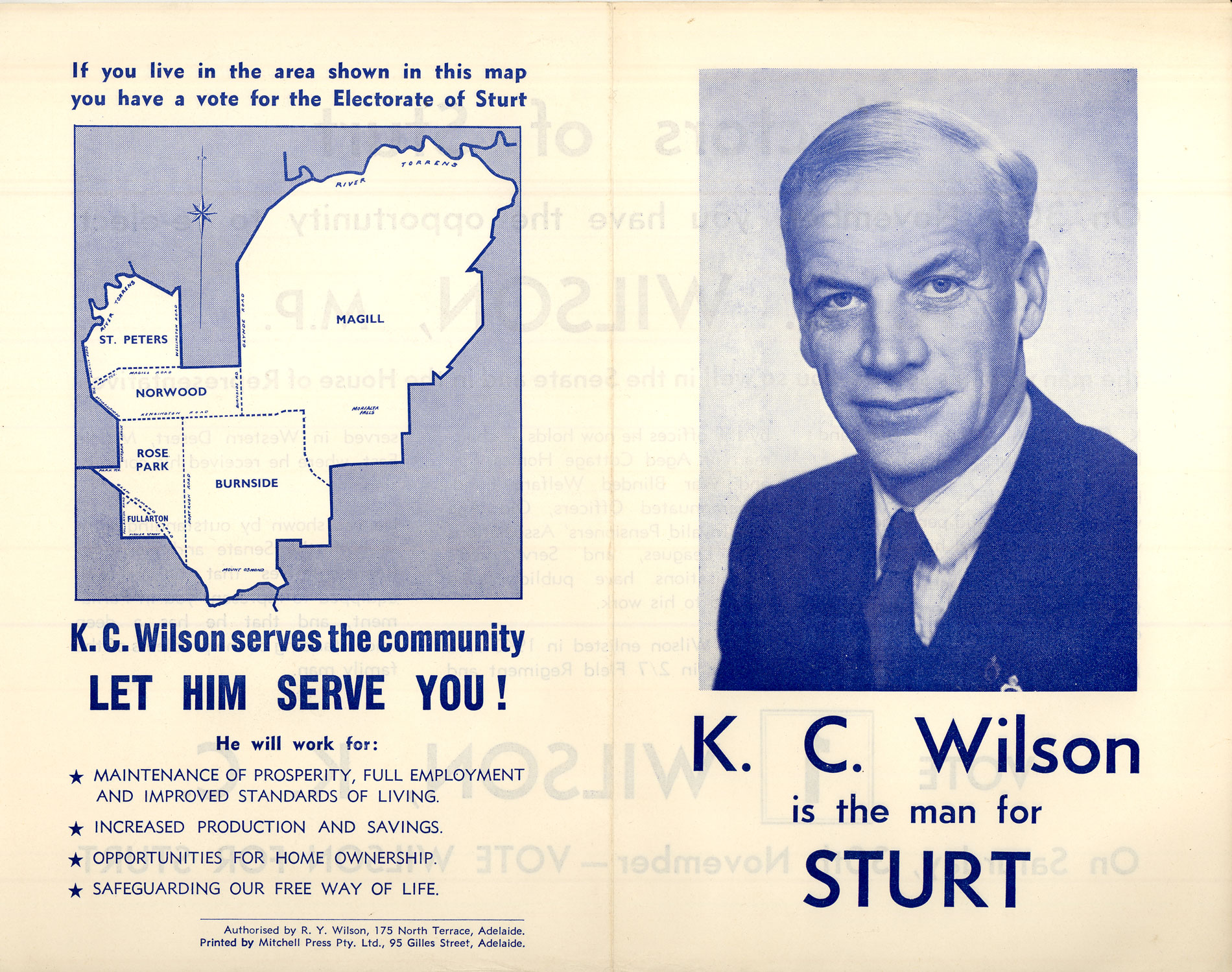

Liberal Party leaflet for K C Wilson's campaign, 1963. Museum of Australian Democracy collection

Australian Democrats leaflet, 1990. Museum of Australian Democracy collection

Election advertising rules apply within a specific election period. As such, there have been instances of misleading advertising outside of this period. Ahead of the 2025 election but prior to the election being called, activist group Advance reportedly distributed flyers to the Victorian electorate of Wannon depicting independent candidate Alex Dyson as an undercover member of the Australian Greens party. In the flyer, a digitally-altered Dyson wears a Superman-style Greens T-shirt underneath his suit. As this communication is outside the election period, it's not considered illegal.

Broadcast blackout period

From the Wednesday before polling day until polling day on the Saturday, political advertising can't be broadcast on TV and radio. However, it can appear online and in print media during this time.

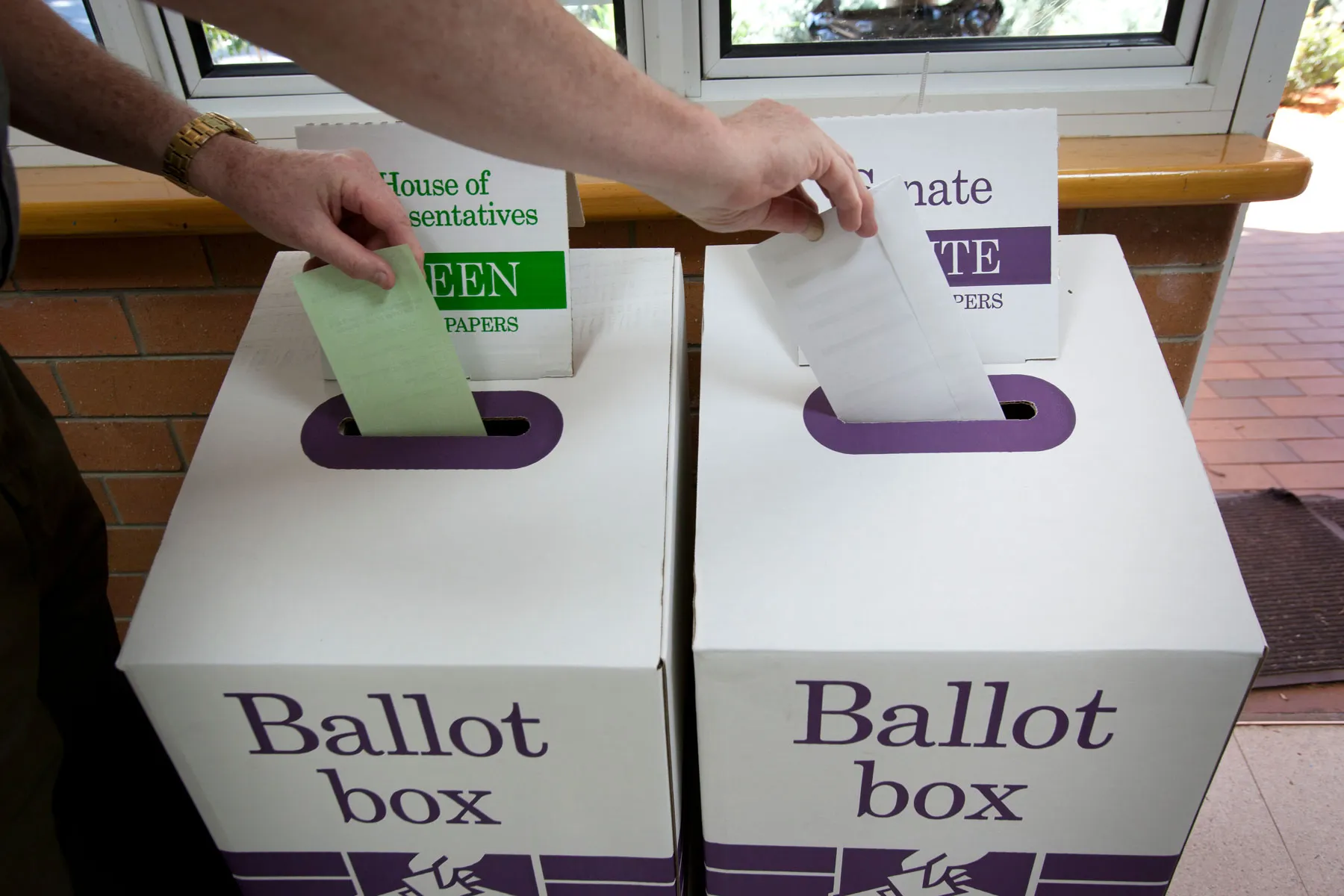

Campaigning at polling booths

In federal elections, all campaign activity – signage, location of campaign staff, canvassing for votes – must be outside of six metres from the entrance of a polling place. This includes using a loudspeaker – it can't be audible within six metres of the polling booth entrance. Other activities not allowed within six metres: soliciting votes, inducing voters not to vote for a specific candidate or not to vote in the election.

Most state/territory and local elections follow this six-metre rule, except for the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). In ACT elections, canvassing for votes is illegal within 100 metres of a polling place.

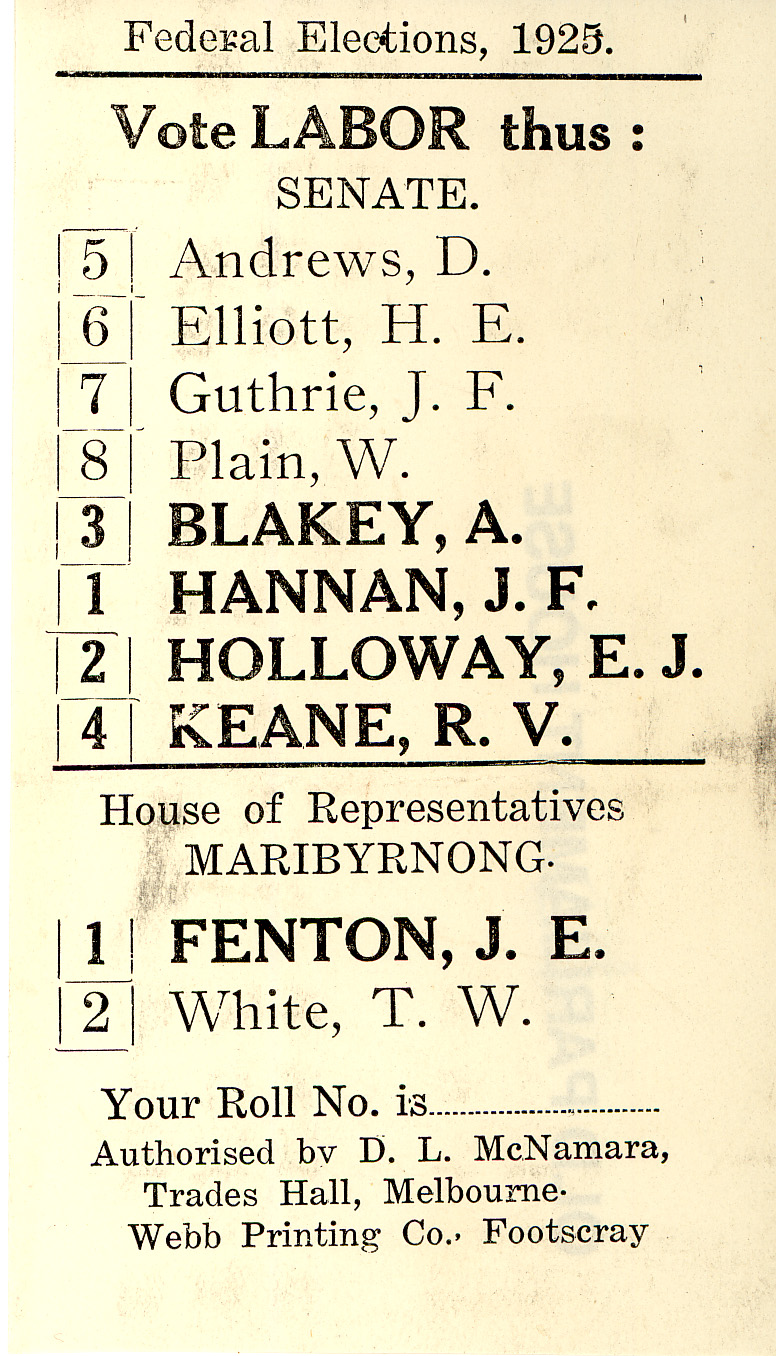

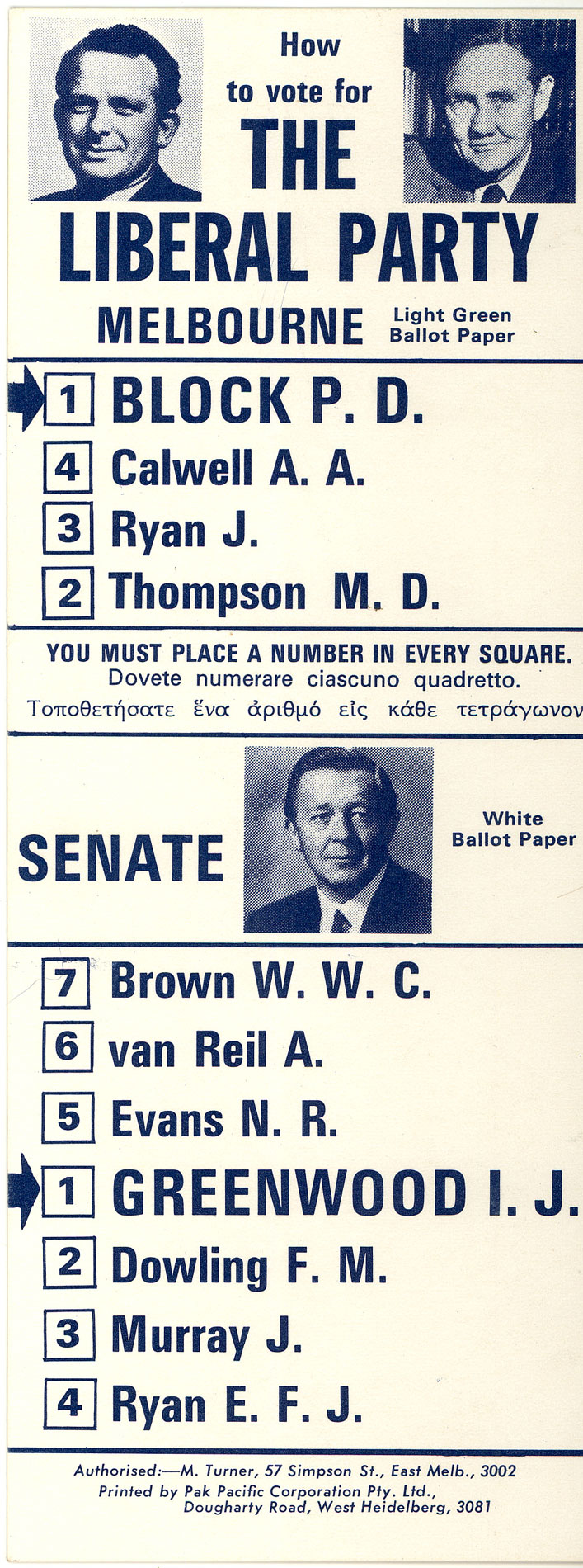

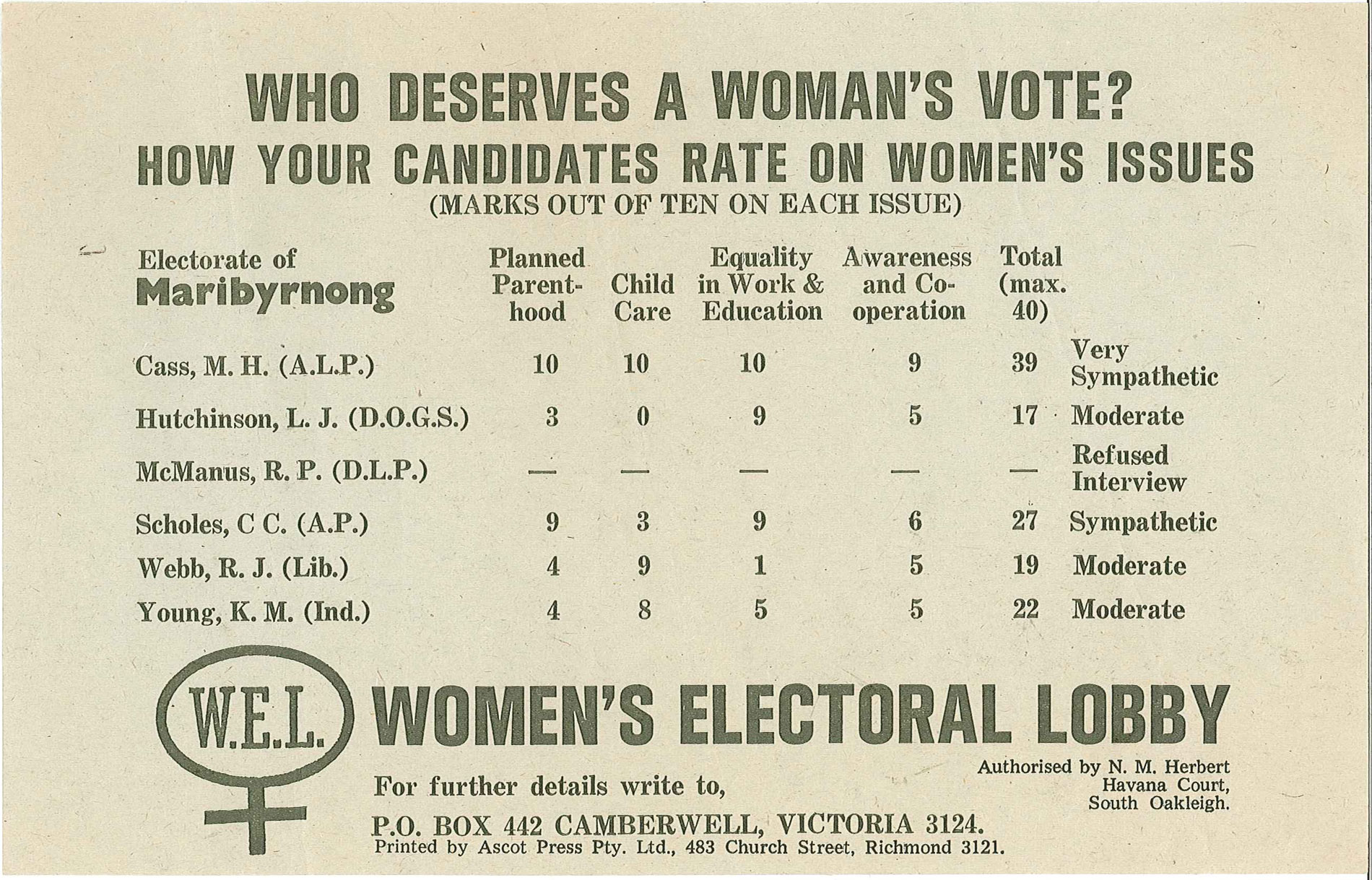

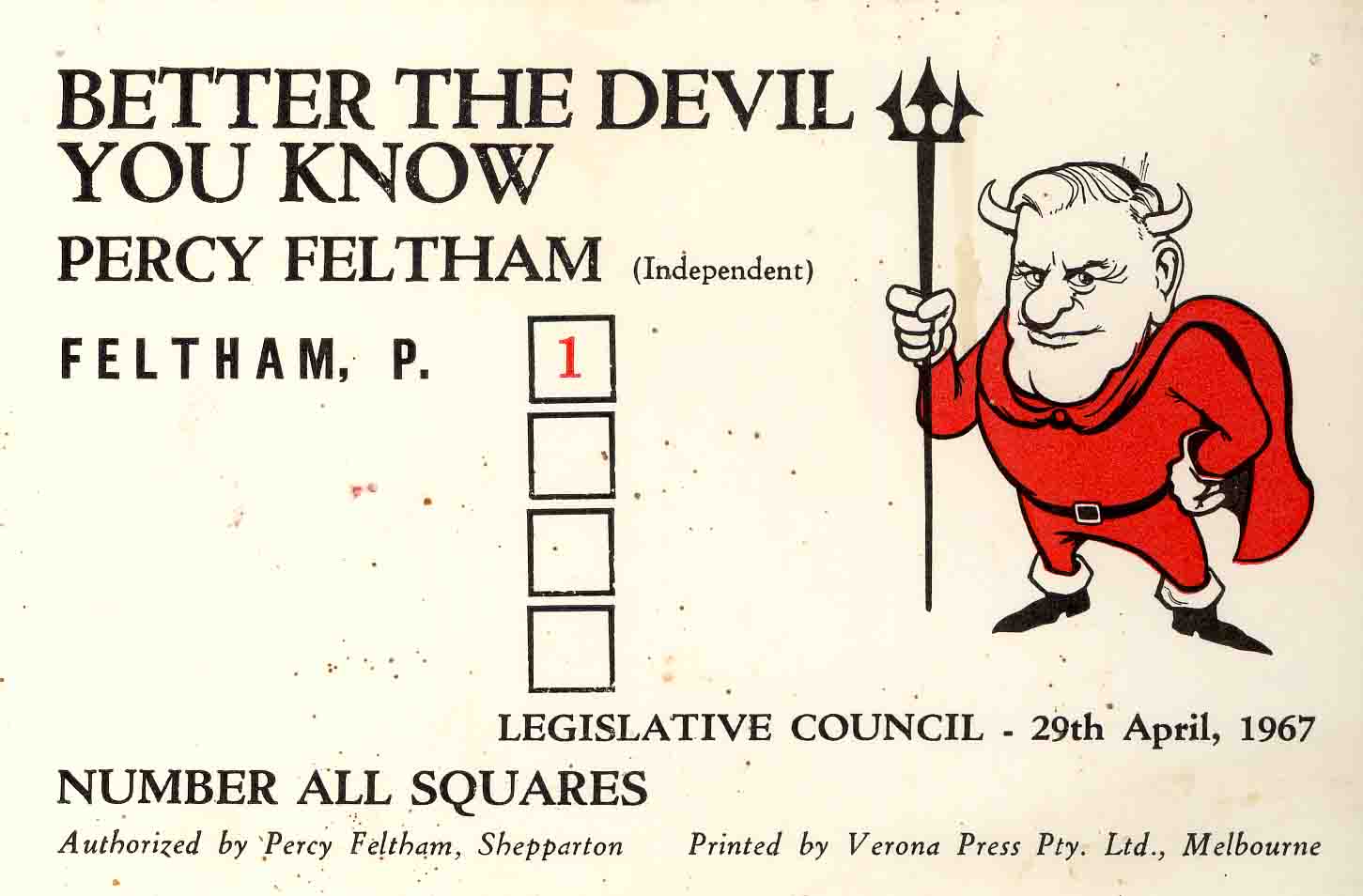

Campaign staff outside polling places may hand out how to vote cards, but you don't have to accept these. How you vote is your decision.

Labor how to vote card, 1925. Museum of Australian Democracy collection.

The Liberal Party how to vote card, 1969. Museum of Australian Democracy collection.

Women's Electoral Lobby how to vote card, 1972. Museum of Australian Democracy collection.

Independent candidate Percy Feltham's 'Better the devil you know' how to vote card, 1967. Museum of Australian Democracy collection.

History of election campaigning in Australia

In the first parliamentary elections in Australia, the 1843 New South Wales Legislative Council elections, campaign tactics to influence voters included 'treating' (giving out food and drinks), along with violence and intimidation. Candidates often campaigned in rowdy pubs, where voting also took place.

Once the secret ballot was introduced in 1856, campaigning and elections became more orderly and adapted to what was available at the time in terms of transport and communication. For instance, in the first federal election in 1901, candidates hit the campaign trail on trains and horse-drawn buggies to deliver speeches in town halls, hotels and parks.

As well as delivering campaign speeches, candidates in the early 20th century used lengthy printed materials to share their policies.

Ephemera related to Australian federal election campaigns.

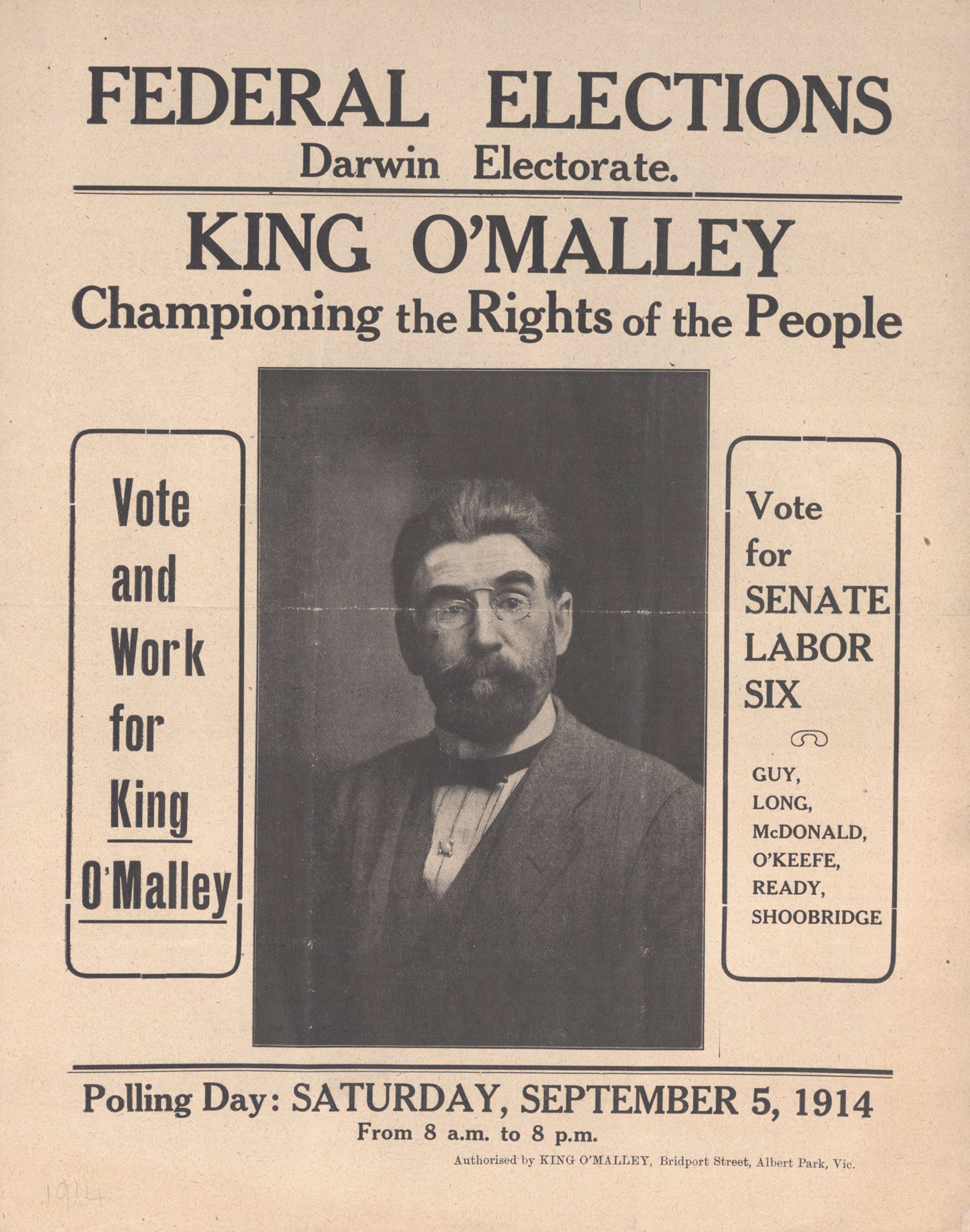

King O'Malley's 1914 campaign material, front page.

National Library of Australia, 132606898

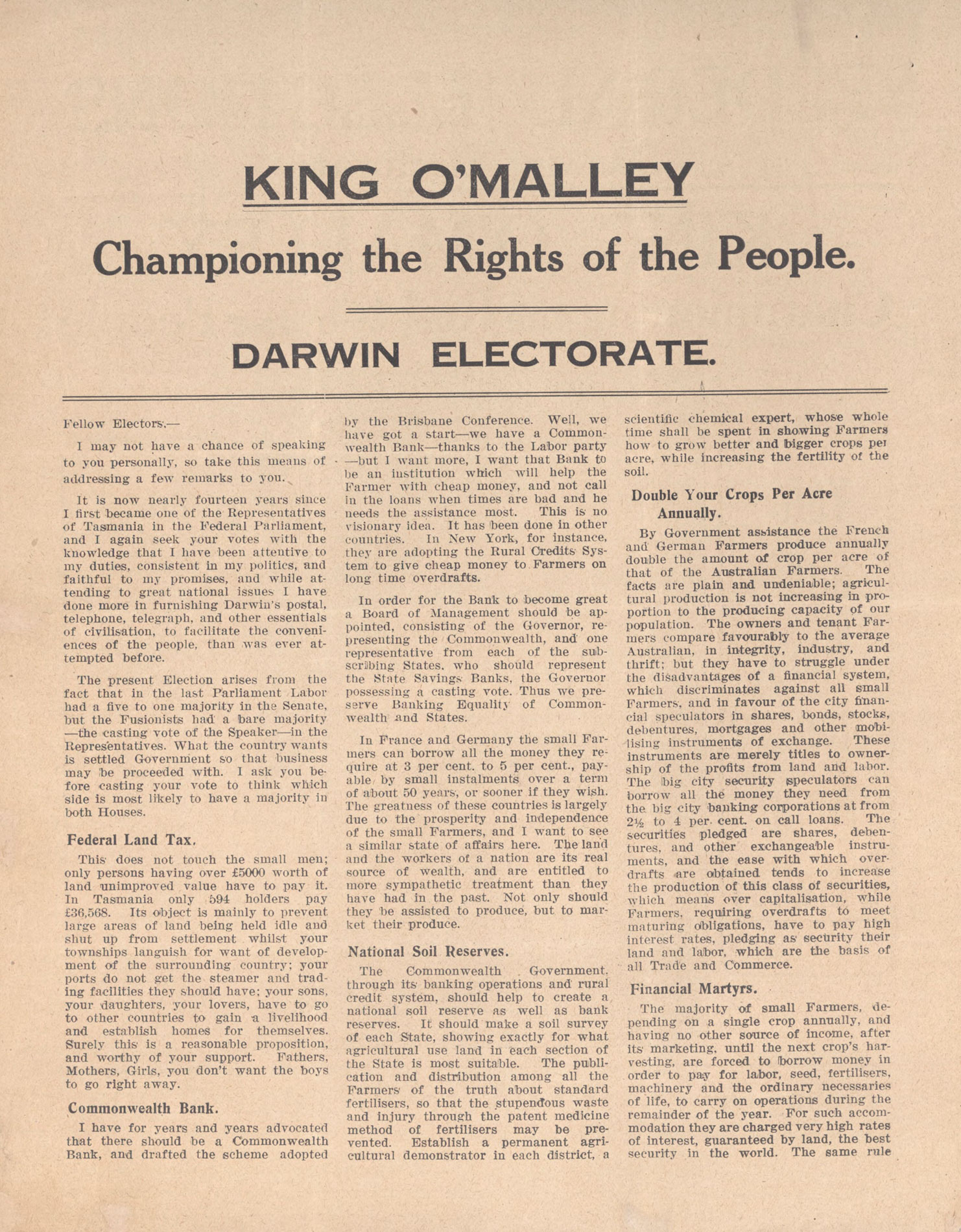

King O'Malley's 1914 campaign material, page two.

National Library of Australia, 132606898

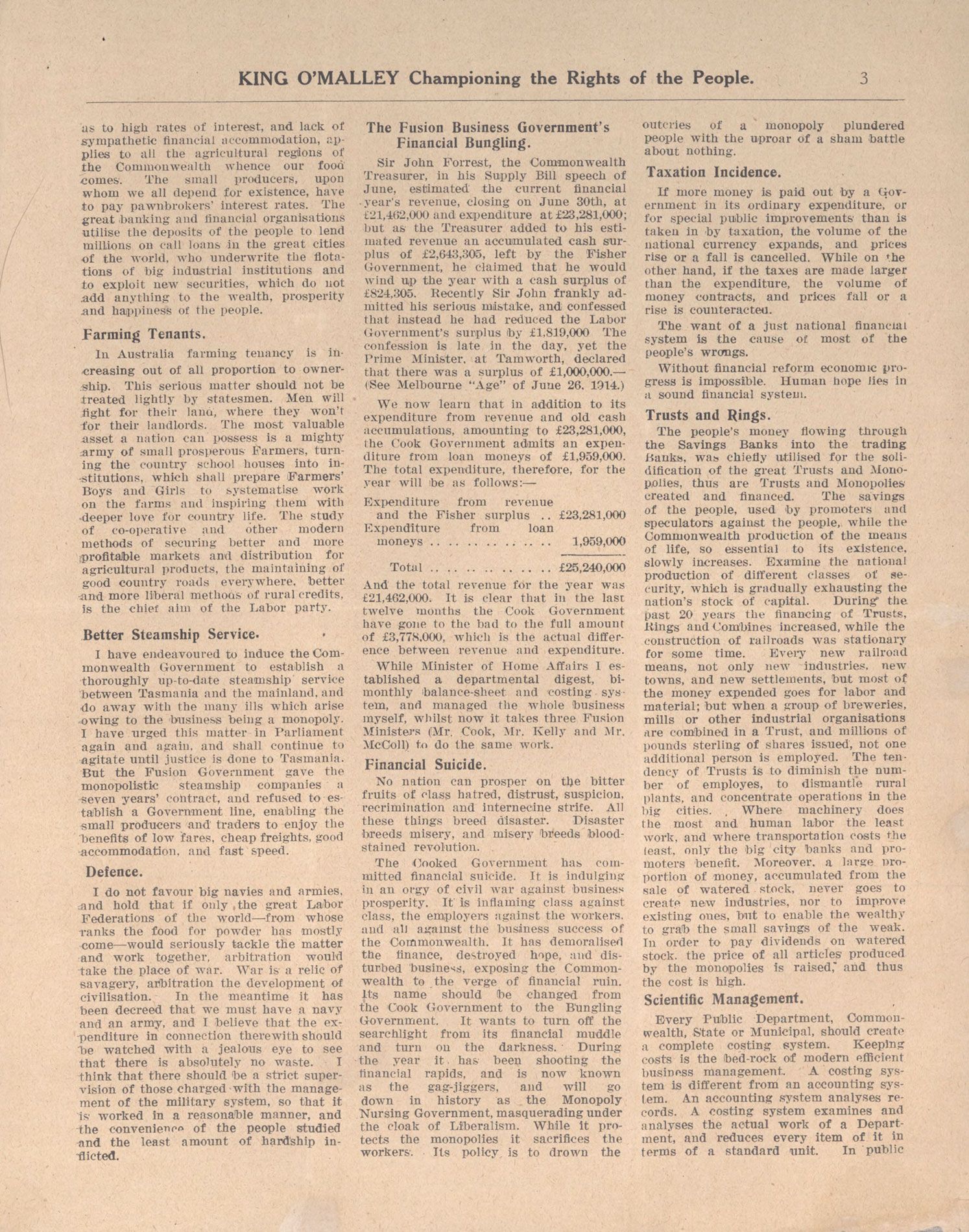

King O'Malley's 1914 campaign material, page three.

National Library of Australia, 132606898

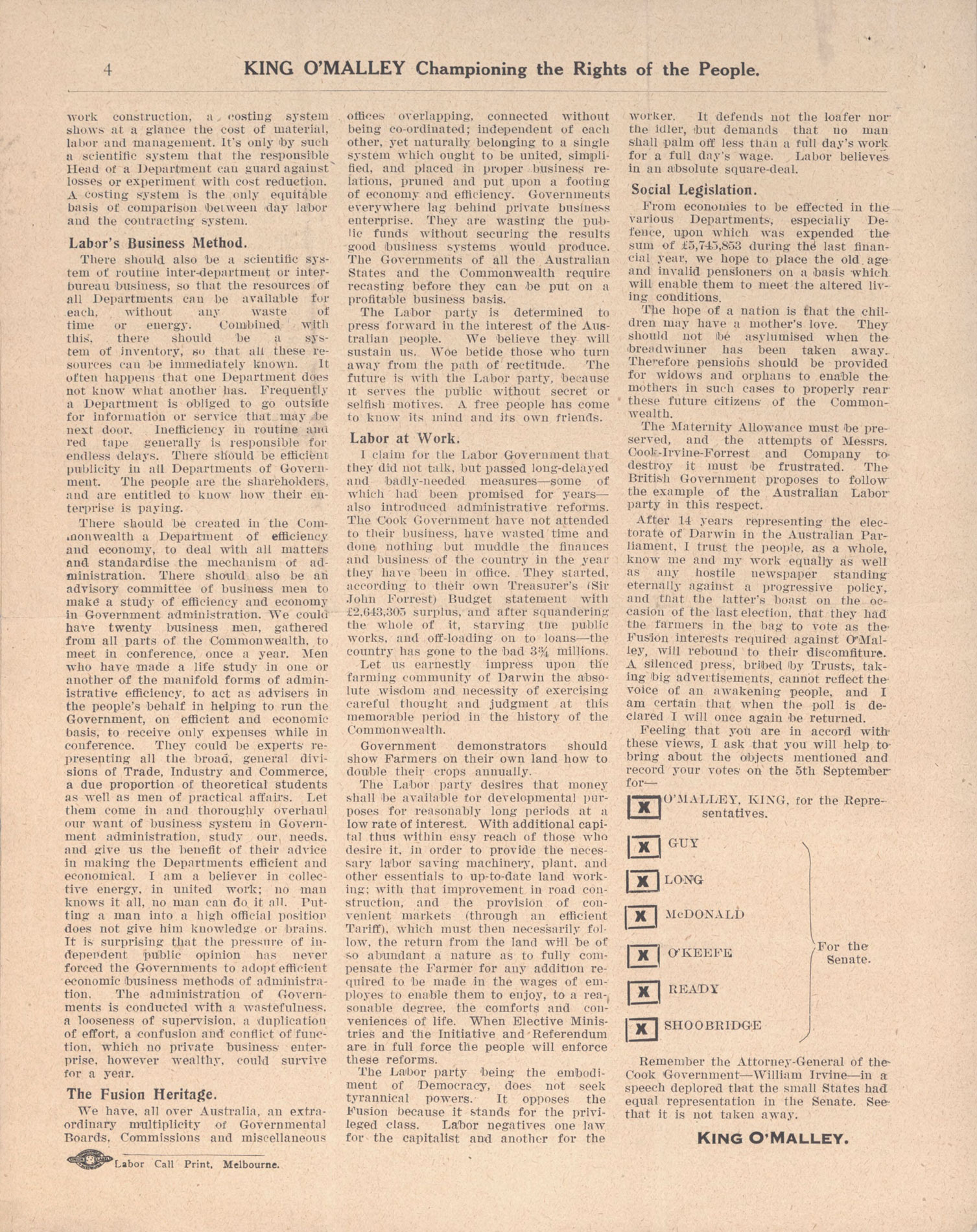

King O'Malley's 1914 campaign material, page four.

National Library of Australia, 132606898

In the lead up to the 1949 election, the Liberal Party turned to radio. The radio serial, John Henry Austral, ran twice weekly for 15 minutes from 1948 to 1949. John Henry Austral, a fictional person voiced by an actor, talked about themes concerning the nation, but in a relatable way to indicate to voters that the Liberal Party understood their concerns and daily challenges. Considered ahead of its time, this campaign was a resounding success. The Liberal-Country coalition soundly defeated the incumbent Labor Party in the 1949 election.

The Labor Party's 1972 'It's time' campaign was another significant campaign. This campaign used market research to create TV, radio, cinema and print advertising targeting key voting demographics. One element was a TV commercial featuring well-known Australian personalities singing a catchy 'It's time' song interspersed with pictures of Labor leader Gough Whitlam engaging with the community. Memorable merchandise included a traffic-stopping orange skivvy, which is in our collection here at the Museum. It was a highly effective campaign and saw Labor win the election after 23 years of a Liberal-Country Party coalition government.

'It's time' skivvy, in the Museum of Australian Democracy collection.

Gough Whitlam with singer Pattie Amphlett wearing 'It's time' slogan T-shirts during the 1972 Labor election campaign.

Photograph Graeme Fletcher/Newspix

Gough Whitlam launching Labor's 'It's time' campaign in Blacktown, 1972.

Photograph NAA: A6180, 5/12/72/6

Contemporary election campaigns continue to employ this strategy of researching the electorate to craft targeted messages for voters, but the communication tools have expanded to include online and social media.

In our collection

Interesting election campaign items in our collection include Michael Darby's campaign matchbook promoting the Liberal candidate who contested Prime Minister Gough Whitlam's seat in the 1974 federal election. Matches were widely used in the 1970s when many people smoked.

We also have 'Cathy's bling' earrings, which were created for independent candidate Cathy McGowan who successfully secured the Victorian seat of Indi in 2013.