Is it compulsory to like compulsory voting?

- DateFri, 31 Jul 2020

There are good arguments, sound, solid, democratic arguments, both for and against compulsory voting.

But I haven't decided if I like it yet.

Voting is not some optional extra in democratic citizenship. It’s the first and ultimately most important act you can perform as a citizen. The whole democracy show, in its modern representational form at least, stands or falls on voting.

If there's no voting – democracy doesn't exist. Democratic citizenship doesn't exist.

Parliament doesn't exist.

Political parties? Governments? Prime ministers? Gone too.

In a modern democracy, there is no legitimate power for leaders and governments to wield and exercise outside of voters voting at elections. Without it there is no democratic legitimacy.

Yes, it's true, you need other things too. 'Rule of law' say. A good constitutional framework. Civil society and the basic rights and freedoms for all individuals. Picking voting and elections out as the most important thing from all of this assemblage is like saying the steering column or the tyres of a car is 'more the car' than the chassis or the hubcaps or the cylinders of the engine. I get that. But take away voters voting at elections? Then I don't care how good your 'rule of law' is. What you're living in isn't a democracy. Not in any representational, modern, post-1700s sense of the word.

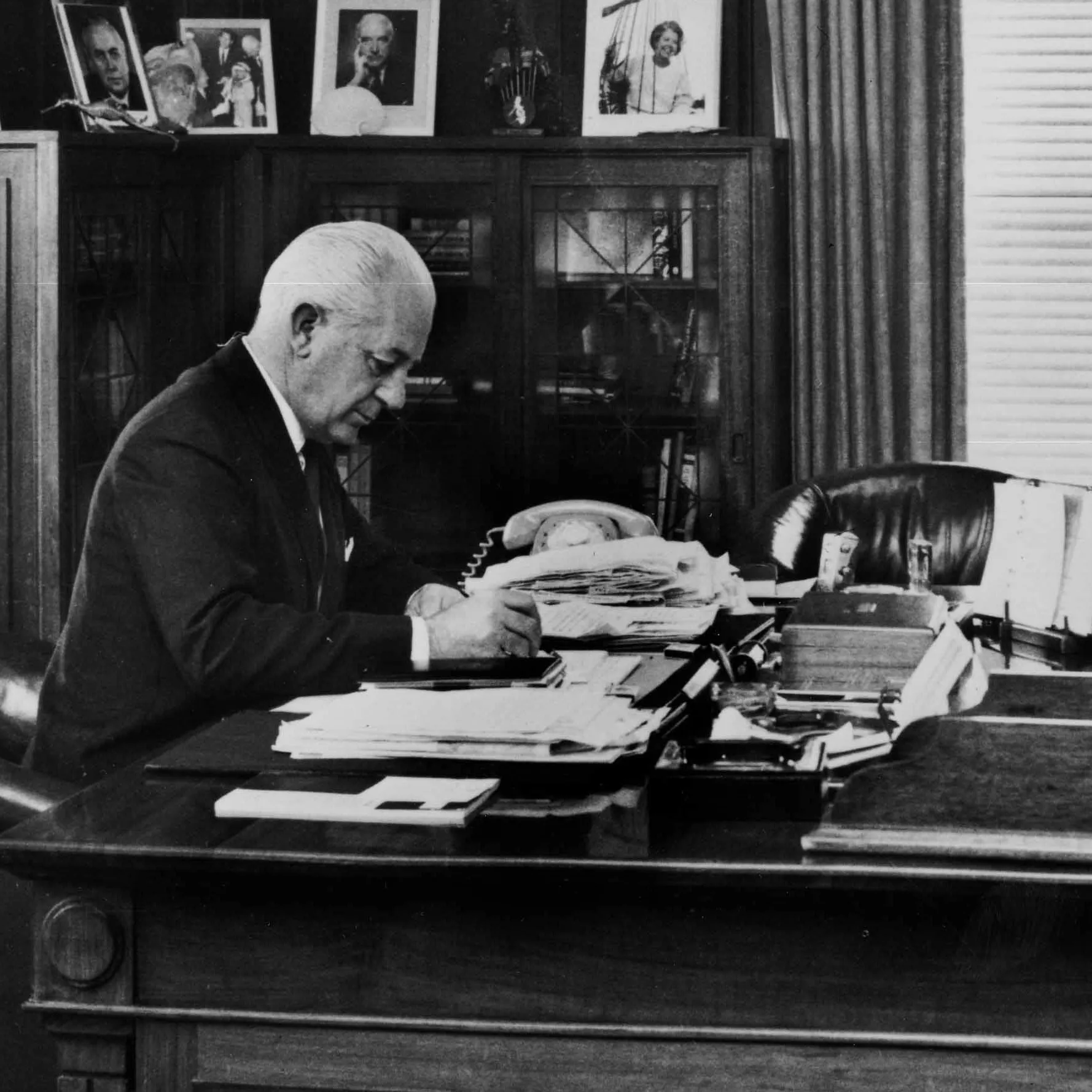

With compulsory voting, Australia has built the ordinary voter in as the core mechanism of its parliamentary democracy more than any other country in the world. Collectively, the entirety of Australia’s citizens share the job of hiring and firing governments every three years.

Unlike just about any other fully functioning parliamentary democracy, Australia's compulsory voting ensures that we are all involved in this momentously critical decision. At election day we do the right thing by our fellow citizens. We perform the democratic citizen's most critical role. We all participate in deciding whether parliaments and their executive governments are fulfilling their mandate of governing for the people. If enough of us decide they're not, they're out, and we give the other mob a go. And it's genuinely decided by all of us. With compulsory voting you know that elections are decided by a true majority of all citizens, not just a majority of those who decide to show up on the day of the election.

Which is great.

But it's funny how it doesn't much feel like that, isn't it?

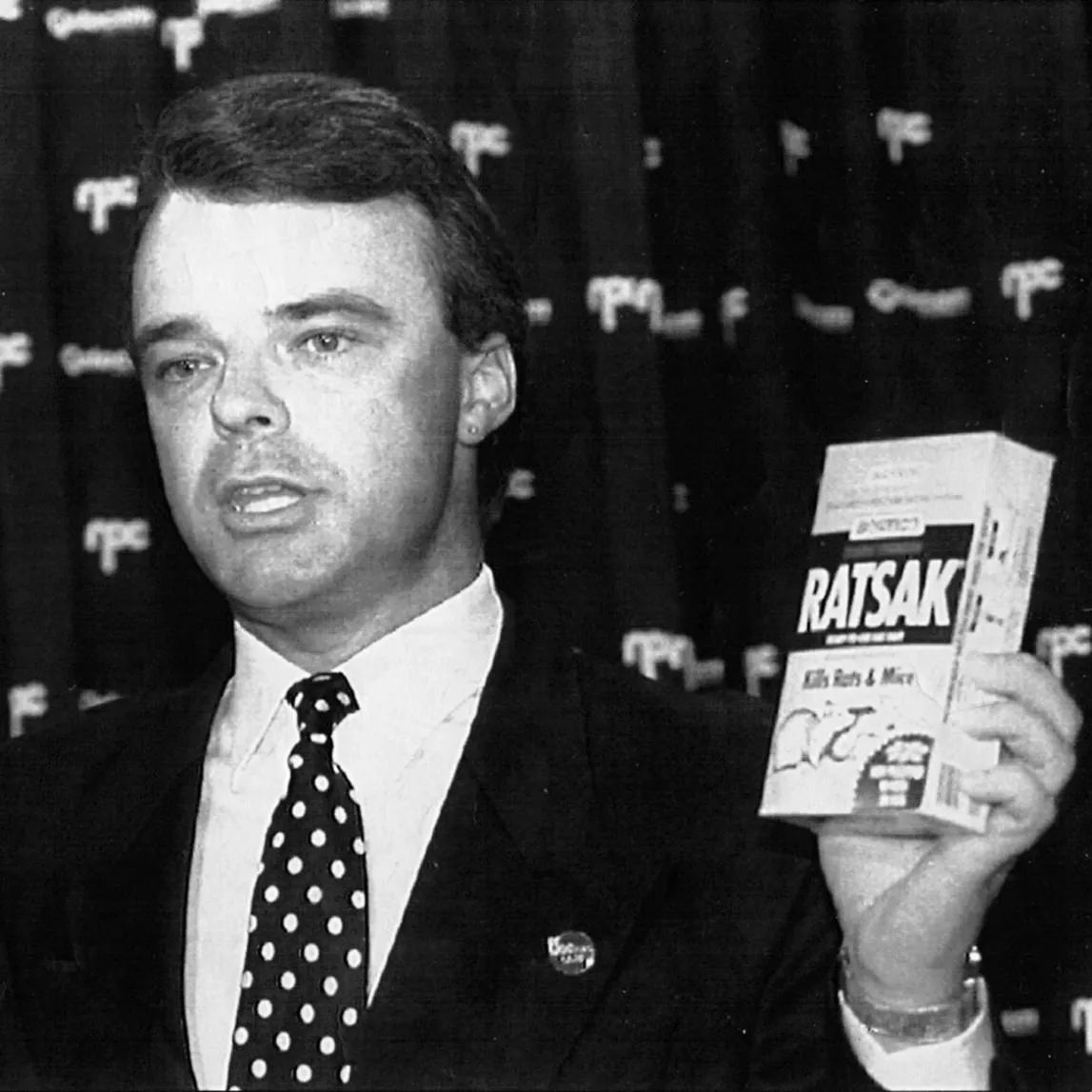

Might there be a link between the intense apathy that so many voters feel and the fact that they have no choice in whether or not to actually vote? Would Australian elections feature such a significant number of informal votes if we didn't actively compel people, by law, to turn up at the polling stations each election day? Seems a good way to ensure that plenty of people won't value the power of what they have in their hands with the vote, doesn't it? Sure, why not – make them do it whether they want to or not, whether they see the point of it or not. Brilliant. That’ll make them really appreciate the power of the act.

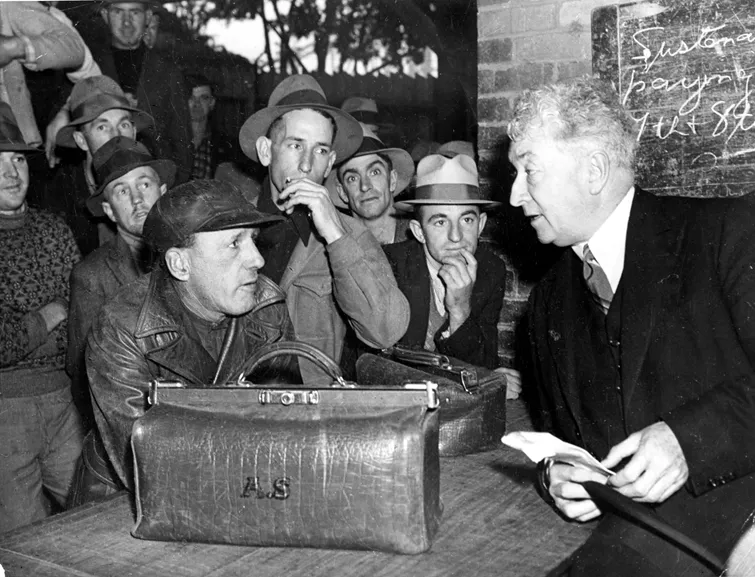

A 2014 MoAD study found that compulsory voting is one of the democratic practices that Australians actually cherish and prize most. Tellingly it is most prized by those who register at the lower end of the socio-economic and educational scale. The less power you have the more reassuring it is to know that everyone will be made to vote come election day.

But these things shift too. The same study shows that the least likely to support compulsory voting in Australia are the youngest demographics. If you're under thirty and reading this you're more likely to agree with most people in New Zealand, or Canada, or the USA, UK, or any country in Europe (ok, fine, barring Belgium and Liechtenstein then) that compelling people, by force of law and significant fines, to exercise their free right to vote, is just plain weird. Perverse even. Possibly, you could say, anti-democratic.

So I haven't made my mind up about this one. The trade-off is tricky. Which is more important? The freedom to decide for yourself? Or the reassurance of knowing that political equality is being realised to an almost maximum extent? On either side of the trade-off something is lost.

Which is why, in any democracy worth its salt, the argument won't ever finish finally. For as long as we're a democracy we get to keep arguing and debating these things – exactly how we best realise core democratic ideals. Exactly how best we govern ourselves.

Long may it continue.