Dr Evatt Goes to San Francisco

- DateThu, 25 Jun 2015

The Second World War was still being fought in the Pacific.

Germany had surrendered to the allies only six weeks before. Europe and Asia were devastated by the largest conflict the world had ever seen. Representatives of 50 countries decided that it could not be allowed to happen again. They met in San Francisco to hammer out an international charter that would create an organisation of all the world’s nations, to solve conflicts and be a diplomatic vehicle to promote co-operation and the peaceful resolution of differences. On 26 June 1945, they signed the Charter they had written, and the United Nations was born.

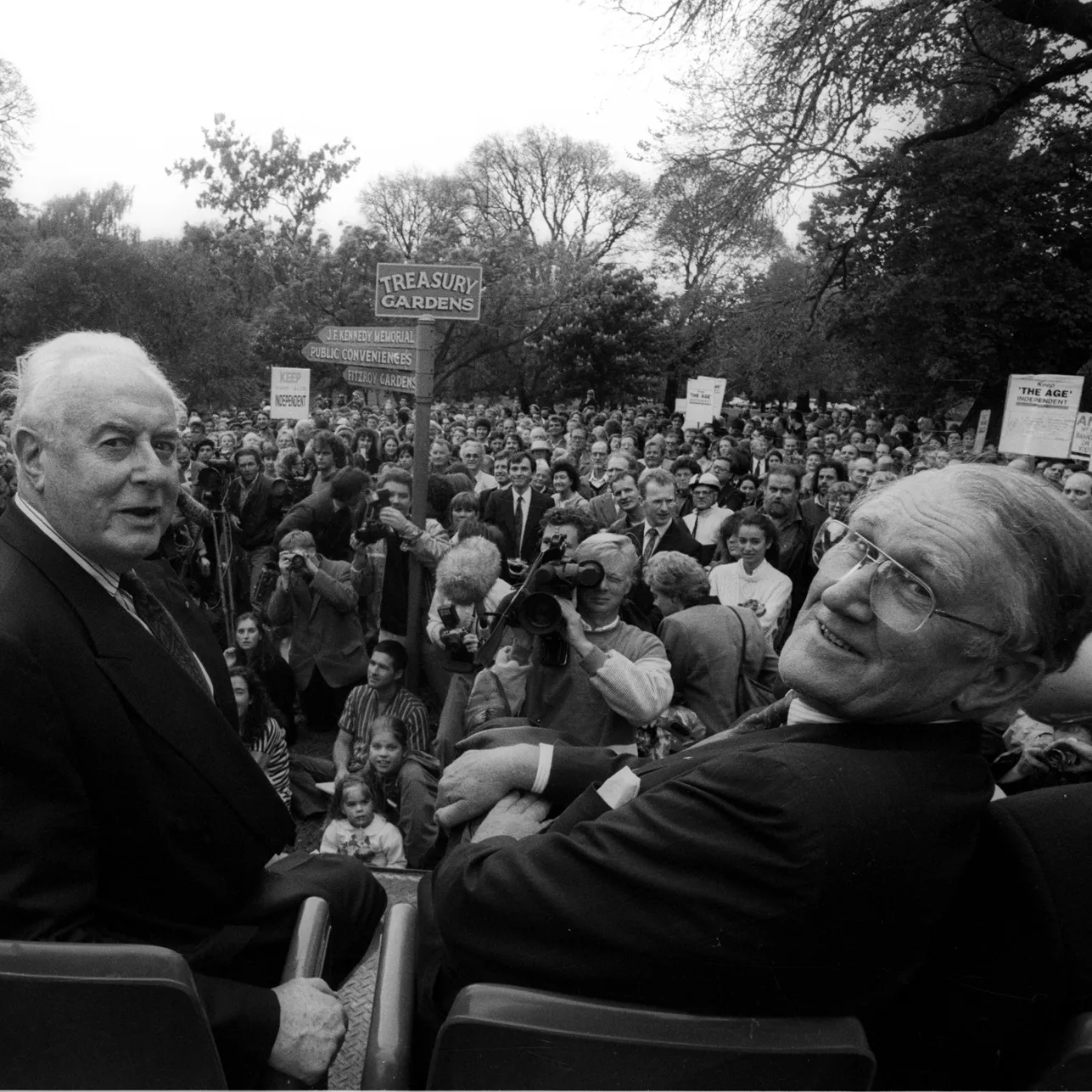

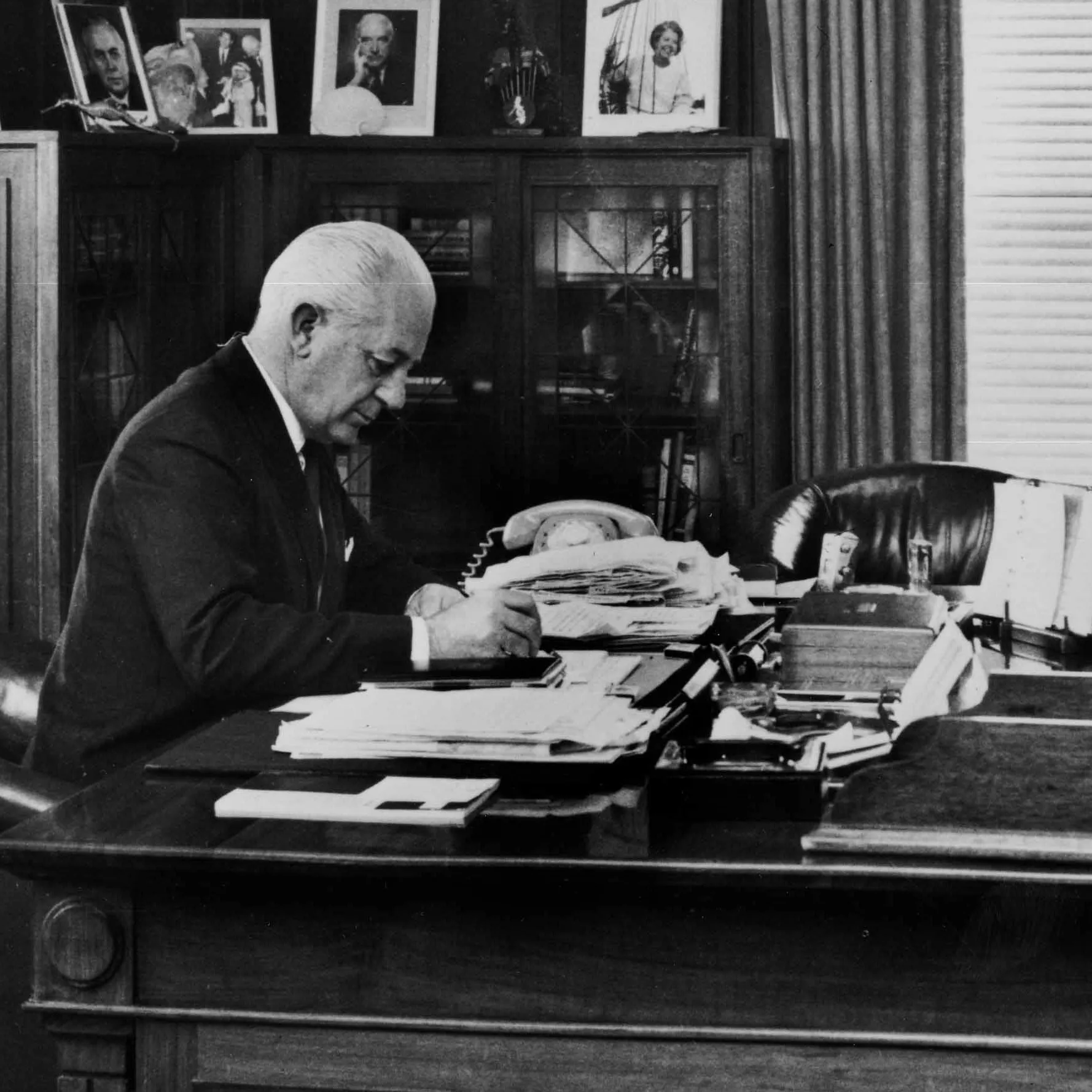

The official foundation of the United Nations is marked on 24 October when it was ratified by a majority of signatories, including the five permanent members of the Security Council – the United States, United Kingdom, Republic of China, France and Soviet Union. However, the date the Charter was signed is a significant one, a kind of pre-birthday, and has a deep and important connection to Australia’s democracy and history through the Hon. Dr Herbert Vere Evatt MP QC. A lawyer, former High Court judge (appointed at just 36 years of age) and parliamentarian, Evatt would later lead the Australian Labor Party through a turbulent period of its history. But at this point in his distinguished career, Evatt (known to his friends as ‘Bert’ and to everyone as ‘Doc’) was both Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs in the government of John Curtin. It was in his capacity as Minister for External Affairs that he attended the United Nations Conference on International Organization (UNCIO) in San Francisco. He had a lasting influence on the Charter and the formation of the United Nations.

The conference began on 25 April 1945. Evatt was not the leader of the Australian delegation, at least in theory; that job belonged to Deputy Prime Minister Frank Forde. Evatt, however, saw himself as the delegation’s real power, to the extent that there were two ‘camps’ of Australian delegates in the hotel in which they were staying, on different floors – one loyal to Evatt, one to Forde. This division, however, didn’t stop Evatt getting things done in San Francisco. As befitted a well-read man with a legal background, Evatt knew his subject well. He bounded between conference sessions with papers in hand, frequently working until two in the morning, and had a strong view on many of the provisions in the draft Charter. He spoke at length about the need for a strong United Nations, and resolutely challenged countries which were self-interested. He was wary of the ‘veto’ power held by the ‘Big Five’ countries, and his advocacy of the causes and rights of small nations won him praise from the international community. But Evatt’s main concerns were economic and social rights. Evatt saw the UN as a global body to help the economically disadvantaged, and fought hard for those goals to be feature in the founding document.

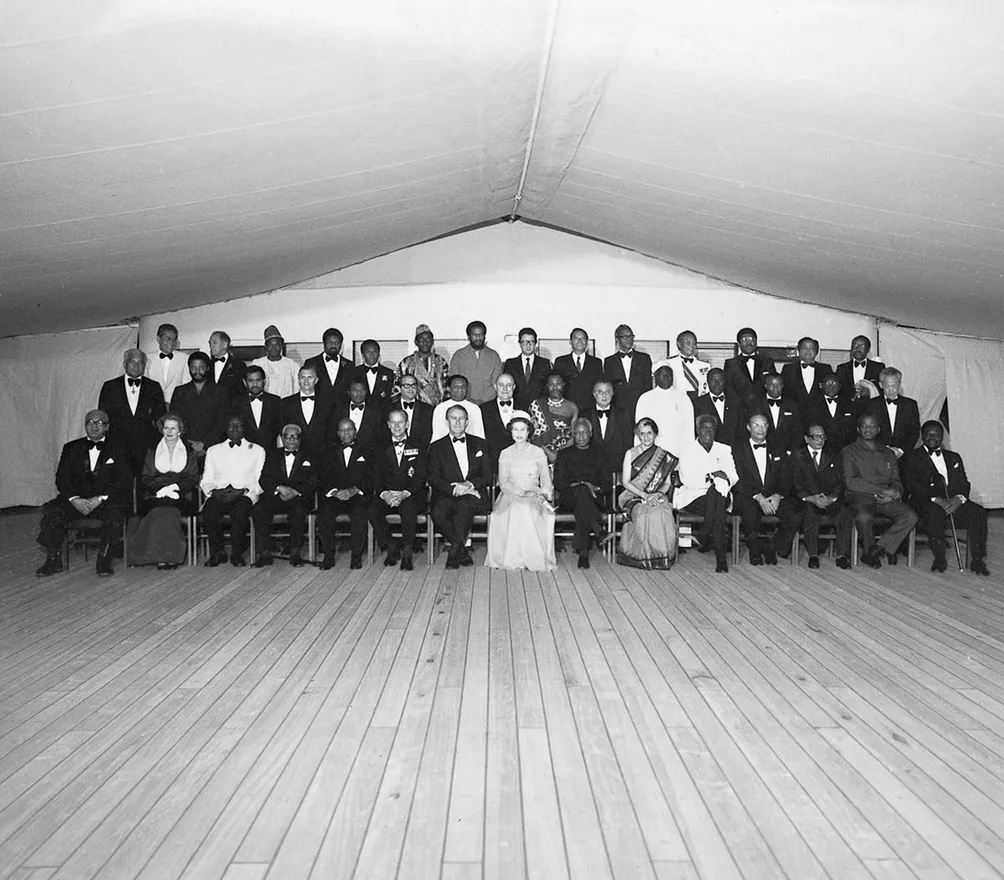

Largely due to Evatt’s tireless work and bombastic, crash-through personality (one British delegate described him as ‘frightful’), Australia submitted 38 amendments at the conference with 20 of them were adopted, either completely or partially. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, ultimately included many of the rights Evatt insisted on including creative expression, reasonable working conditions and access to education. Evatt was instrumental in framing this document, and his work at the UN saw him elected as President of the General Assembly for the 1948-49 session in New York.

As committed as he was to human rights, Evatt was also a defender of the White Australia Policy. While he fought for the self-determination of native peoples and for the decolonisation of the world by European powers, Evatt fought against some of the racial equality clauses in United Nations’ documents. Like most of his generation, Evatt’s view was not necessarily about superiority of one race over another, but was rooted in economics and workers’ rights. There was a strong view in Australia that any softening of the White Australia stance might result in cheaper labour being imported from overseas. Another prevailing sentiment was that multiculturalism resulted in instability. Evatt, opposing resolutions which could have led to more Asian immigration to Australia, told the Chinese delegation at San Francisco:

'You have always insisted on the right to determine the composition of your own people. Australia wants that right now. What you are attempting to do now, Japan attempted after the last war [the First World War] and was prevented by Australia. Had we opened New Guinea and Australia to Japanese immigration then the Pacific War by now might have ended disastrously and we might have had another shambles like that experienced in Malaya.'

Evatt was referring to racial tensions in Malaya (now Malaysia) before and during the Second World War, between local Malays, Chinese and Japanese.

Evatt wasn’t the only Australian to have a major influence on the UN Charter and global human rights. Another delegate to the San Francisco conference was feminist organiser Jessie Street. She was the only woman in the Australian delegation, and it was her influence that saw a major and crucial addition to the Charter. Of the 850 full delegates to the conference, only eight were women; the others were Brazil’s Bertha Lutz, the United States’ Virginia Gildersleeve, Åse Gruda Skard of Norway, Cora T. Caselman of Canada, Minerva Bernardino of the Dominican Republic, China’s Wu Yi-fang and Isabel P. de Vidal of Uruguay. They made up less than one percent of delegates, but made an enormous impact on the shape of the UN Charter and the organisation it created.

Article 1, part 3 of the Charter reads:

[One purpose of the UN is…] 'To achieve international co-operation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.'

The inclusion of the word ‘sex’ was Jessie Street’s influence. ‘Where the rules are silent’, Street said, ‘women are not usually considered’. Jessie Street’s advocacy for women made her the leading feminist of her day, and her influence was felt worldwide as she, too, had a strong impact on the subsequent Declaration of Human Rights.

Street and the other women delegates also introduced a major clause to the Charter. Article 8 states:

'The United Nations shall place no restrictions on the eligibility of men and women to participate in any capacity and under conditions of equality in its principal and subsidiary organs.'

This clause was opposed by the United States and the United Kingdom, which felt it was unnecessary. Street and Lutz particularly, along with the South African leader Jan Smuts, campaigned for the inclusion of the clause, and eventually won the day, despite the US and UK opposition. Street said:

'At the present time in practically every country women are excluded from occupying various positions just because the law does not specifically state that women are eligible. I ask that this committee take the necessary action to leave no doubt in the minds of anybody at the present time, or that no doubt can be raised in the future as to the eligibility of women to hold any position at all in the United Nations Organisation … I consider it most important because the question has been raised that as there is no discrimination in the Charter therefore the right of women to participate in all the activities of the International Organisation is not challenged. We wish it to be specifically stated that there shall be no discrimination on any plane.'

The same group successfully lobbied for the United Nations Economic and Social Council to include a Commission on the Status of Women, of which Jessie Street was the first Vice President.

With the signing of the Charter on June 26 1945, and its adoption on October 24 1945, human rights and democratic freedoms had become enshrined in international law. Over the last 70 years the UN has organised peacekeeping forces in more than 70 conflicts and has played a leading role in promoting the resolution of differences by peaceful means. The UN’s humanitarian roles have included providing food aid to areas ravaged by war or disaster, promoting agricultural development and, through the World Health Organisation, eradicating and containing outbreaks of infectious diseases.

Over 70 years the United Nations and the World Health Organisation, have worked to eradicate outbreaks of infectious diseases. Here an official administers Smallpox vaccines in Kinshasa in 1962. United Nations photograph.

Wearing the distinctive United Nations colours, a peacekeeper contributes to the resolution of conflict in South Sudan in 2013. United Nations photograph.

At the Museum of Australian Democracy, we acknowledge Doc Evatt, Jessie Street and all the pioneering diplomats and leaders who helped make the United Nations what it is today, and who made Australia a cornerstone of international human rights law.