Commemorating Prince Philip, the Queen’s strength and stay

- DateSun, 10 Apr 2022

On the occasion of their 50th wedding anniversary in 1997, Queen Elizabeth II said of her husband Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh that ‘… he has, quite simply, been my strength and stay all these years’.

As prince consort, Prince Philip had a major impact throughout Britain and the Commonwealth, sharing a committed and deep-felt relationship with Australia in particular. It has been estimated that Prince Philip’s 23 visits to Australia—many involving visits to Old Parliament House in Canberra—meant that he visited Australia more than any other member of the British royal family.

Prince Philip was born in Corfu on 10 June 1921 into the Greek and Danish royal families, and was exiled to Paris when he was one year old. After successful schooling in Scotland, England and Germany, Prince Philip entered the Royal Navy in 1939. It was here that he had his first proper meeting with the young Princess Elizabeth who, in 1947, would become his wife. After the death of King George VI in 1952, Elizabeth became queen and Philip left the armed services to take up his role as prince consort.

Before his retirement from public engagements in 2017, the Duke of Edinburgh undertook no fewer than 22,219 royal engagements over six decades throughout Britain, the Commonwealth and the world. One of the longest and most extensive royal tours was his and the Queen’s 1954 visit to Australia, the first-ever visit to Australia by a reigning monarch.

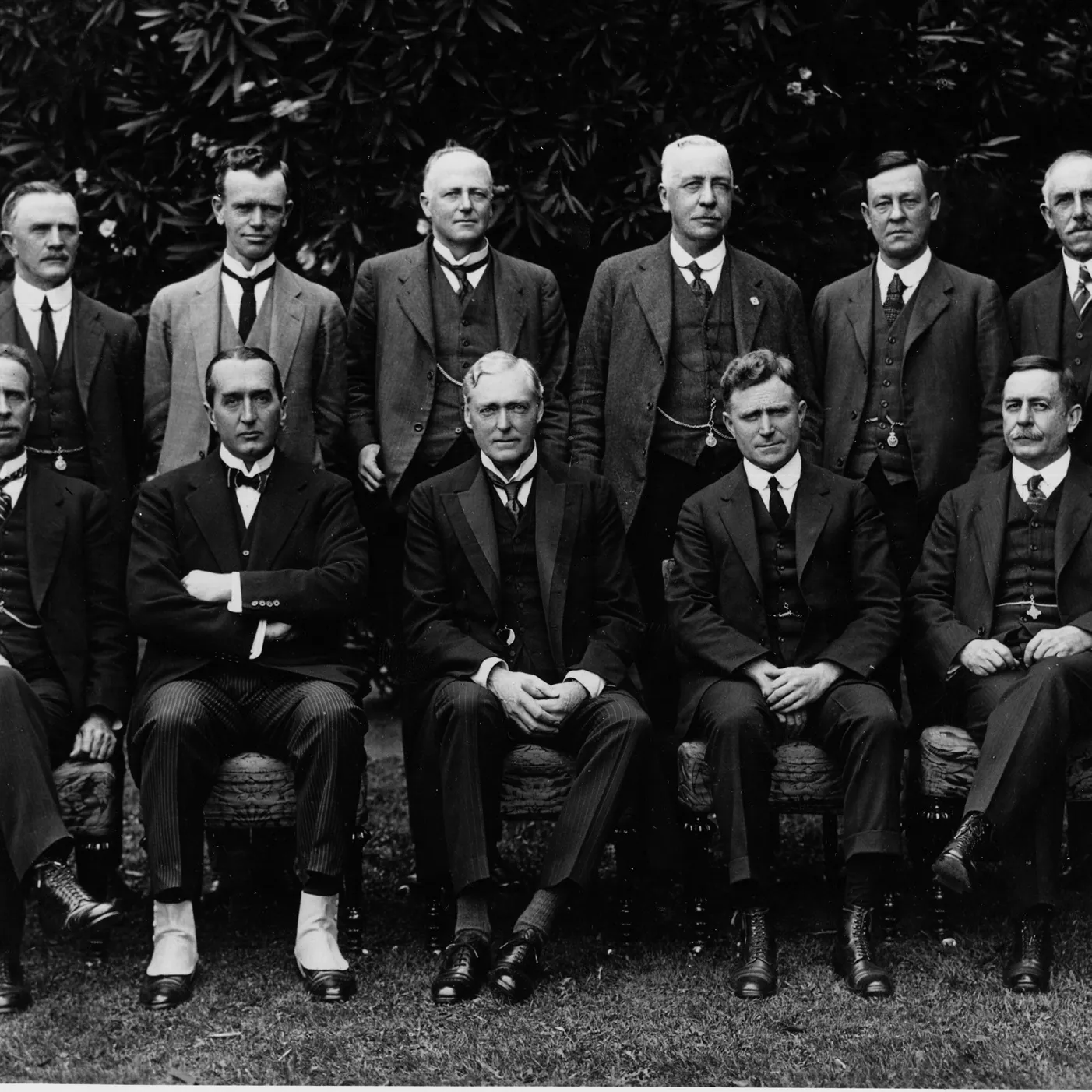

He was alongside the Queen when she opened the federal parliament in Canberra. He was also with her when the couple attended a state banquet hosted by Prime Minister Menzies, a dinner at which ideological lines were drawn when SA Labor MP Clive Cameron objected to the formal dress codes and criticised a young Gough Whitlam for appearing in white tie and tails.

Prince Philip seated beside Queen Elizabeth II at the opening of the third session of Parliament, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 15 February 1954. Credit: National Library of Australia.

The state banquet was just one of many engagements in a tour that covered 58 days, 57 cities and towns across all States and the ACT, and where an estimated 75 per cent of Australians turned out to see the royal couple.

Loud and prolonged cheering met the Queen and Prince Philip as they waved to the assembled crowds before the State Banquet on 16 February 1954. - National Archives of Australia, A2756, RVK62

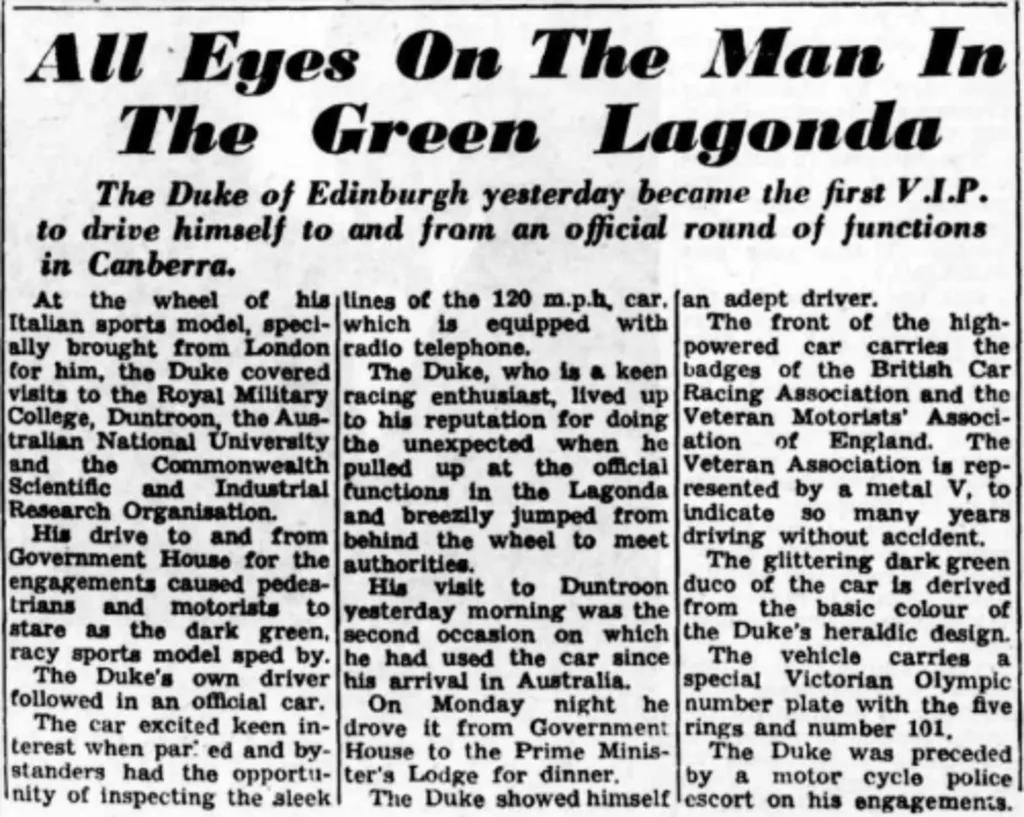

Prince Philip displayed his independent spirit and innovative approach to royal tours when he returned alone to Australia in 1956 to open the Olympic Games in Melbourne, bringing with him a green Aston Martin Lagonda to ferry himself around. The Canberra Times reported that, ‘The Duke … lived up to his reputation for doing the unexpected when he pulled up at the official functions in the Lagonda and breezily jumped from behind the wheel to meet authorities.’

Prince Philip caused a splash by driving himself around in a dark green racy Lagonda. - The Canberra Times, 21 November 1956, p1

In 1962, the Duke opened the British Empire Games in Perth, and in the following year accompanied the Queen for the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the founding of Canberra. Robert Menzies, in his fourteenth year and second term as prime minister, allocated an enormous budget to the beautification of Canberra for this visit—a gesture that even Menzies may have regretted when two years later the Duke, returning to open the Royal Australian Mint, commented that planned structures like Canberra ‘lacked soul … [and] a little something of the human cussedness which makes a town worth living in.’

The prince toured Australia in 1967, 1968, 1970 and 1971, the last of which saw him in Canberra overseeing celebrations of the 50th anniversary of the Royal Australian Air Force and the establishment of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award promoting youth improvement.

In 1970, the Duke gained the approval of Australian conservationists for his spirited defence of native species. On a return visit in 1973, however, he was criticised as the president of the Australian Conservation Foundation for urging greater flexibility between conservationists and developers. The Duke’s ensuing run-in with conservationists and the press led then Prime Minister Gough Whitlam to quip drily during a parliamentary luncheon that he had been ‘the first Prime Minister since Sir Robert Menzies [who] has been able to survive a second visit from Prince Philip’, given that the Prince had been the ‘Nemesis of Australian Prime Ministers’ due to his statements about public policy. The Duke, Whitlam added archly, had now ‘eschewed all forms of political activity [and] devoted himself to many good causes in this nation’ allowing the Prince, unlike some Australian politicians and various species, ‘to survive’.

Throughout the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, Prince Philip made a number of trips to Australia, many of which involved appearances at Parliament House in Canberra, including the historic visit in 1986 to accompany the Queen when she signed the ‘Australia Act’ that made Australian law independent of British parliaments and courts.

Never one to settle for being a mere ribbon-cutter and unveiler of commemorative plaques, Prince Philip remained Queen Elizabeth’s strength and stay, and demonstrated consistently and often that he was an active and interested observer of Australian life.