The strange provenance of the Fairfax collection

- DateThu, 29 Nov 2018

Provenance relates to the origins of an object.

Researching provenance history is intricately linked with ensuring legal title and ethical industry standards. These things matter. A lot.

But sadly, not all objects come directly from the creator. The process of tracking an object’s history can be tricky, leading down unexpected roads, with a few breaks in the bitumen along the way. To extend the journeying metaphor further, even relatively young objects from stable homes, can take wild adventures on their way to safety.

This is a story about 658 Australian photographs from the Fairfax Media archives that were recently acquired by the Museum of Australian Democracy – a story that includes an FBI raid, divorce suit, illegal ebay sales, and a complicated legal battle. The sordid saga begins in 2013, with the photographs landing in Little Rock, Arkansas, in the United States, in the hands of a fraudulent digitisation outfit called Rogers Photo Archive.

Rogers Photo Archive was the front presented by owner John Rogers, a sports memorabilia and heritage photography enthusiast who claimed to have been digitising American newspaper archives since 2009. Rogers offered to digitise the Fairfax Media hard copy photographic archive – 8 million images – and pay $244,000 for the privilege. In exchange, Fairfax Media would receive digitised copies complete with metadata. Crucially, Fairfax Media would also retain economically precious copyright for each image. Once digital versions were delivered to Fairfax Media, Rogers would be free to keep the hard copy versions and do as he pleased with them. As the ABC’s Lisa Miller explains, ‘It seemed like a brilliant deal for Fairfax Media, which had to find a way to save its valuable archival photos from deteriorating but could not spend a fortune doing it.’

Sadly, only months after the photographs arrived, the FBI raided the Rogers Photo Archive premises while investigating John Rogers for fraud. The FBI believed Rogers had been selling fake sports memorabilia for significant sums of money.

An American court took possession of the John Rogers Photo Archive premises and contents, including the Fairfax Media archive along with material from a number of American newspapers. Frozen in Julian Assange like limbo, the digitisation contract was incomplete and the ownership of the photographs unclear. To unravel the mess, of what belonged to who and where all the money had gone, the courts appointed a Receiver. He set about auditing John Roger’s assets and negotiating with various parties of interest, including Fairfax Media.

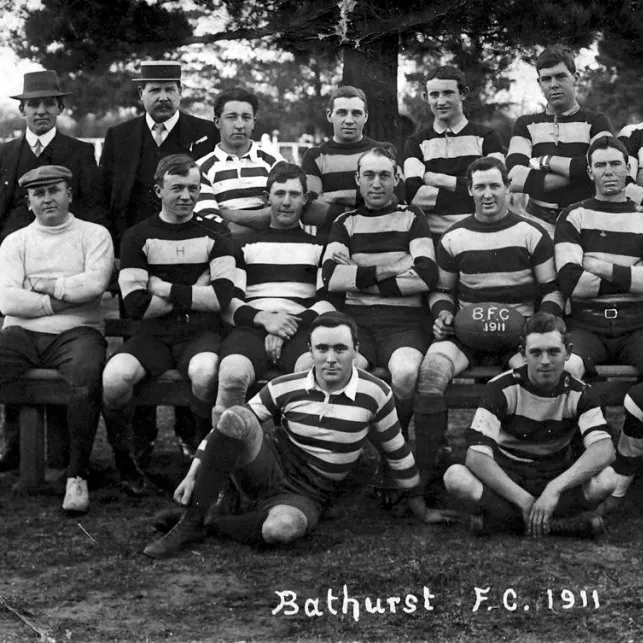

From left: Sir Joseph Cook in an aircraft, 1914; Edmund Barton in Venice with Jane Barton and others, 1902; William 'Billy' Morris Hughes speaks to a crowd from a balcony, date unknown. All photographs from the Fairfax Media archive, now in MoAD Collection.

It was about this time that John Roger’s wife, Angelica, filed for divorce. When the process was finalised in November 2014, Angelica took ownership of the couple’s assets, including aspects of the Rogers Photo Archive holdings, not yet seized by the Receiver, including some Fairfax Media Photographs. It seems understandable to divorce a spouse who has just been accused of large-scale fraud by the FBI. However, according to George Waldon of the Arkansas Business, who has been following the story closely from the start, 'They were still popping up around town together, looking pretty chummy. It could be a divorce of convenience. With this story, who knows?'

The following year, the court-appointed Receiver discovered that Angelica Rogers had not accurately described the number of Fairfax photographs still in her possession and had been secretly selling the photographs online for personal profit. This led to another raid, this time of Angelica Rogers’ home. The Receiver took possession of a large number of photographs in Angelica Roger’s possession. However, those photographs already sold online were considered by the Receiver to be likely lost forever.

Eventually in 2015, the court-appointed Receiver entered into legal negotiations with Fairfax Media to complete the digitisation contract. In 2016, the digitisation for Fairfax Media was completed and the Receiver took control of the hard copy Fairfax Media assets.

In 2017, John Rogers pleaded guilty to charges of fraud.

Just as one American salesman left the picture, another entered, this time thankfully with a noticeably different approach. About 2 million photographs were sold to Daniel Miller, of Duncan Miller Gallery in Los Angeles. The collection was renamed the ‘Sydney Morning Herald Vintage Photo Archive’. The gallery launched a campaign to return the photographs to Australian collections. Daniel Miller travelled to Australia, holding meetings and talks about the collection around the country, while trying to entice Australian buyers. When speaking to ProCounter Australia, Miller described his motivations for purchasing the archive:

‘When I discovered this (Australian) collection was available, and was set to be broken into little pieces, it made me a little crazy….I’ve been working with lots of people, trying to responsibly repatriate parts of the archive back where it belongs. It just seems like the only, and the right, thing to do.’

After confirming correct title with representatives of Fairfax Media, MoAD entered into negotiations with Duncan Miller Gallery. In 2017, MoAD purchased a group of 658 photographs associated with 20th century Australian politics. Late in 2017, after travelling half way around the world, two modest boxes of photographs arrived at the Museum of Australian Democracy in Canberra.

It took months for MoAD staff to research and lock down the complex history of these objects. We were amazed by the story that unravelled through the resulting research. Only when we were confident about the provenance and title of these objects were they finally proposed for acquisition. The history of these objects, like so many others from the MoAD collection, is as interesting as the objects themselves. Now the work begins to correctly process the photographs and add them to the collection. Another chapter in the story of these objects is just beginning. We are excited to provide these photographs with a safe home so that we can share them with you and preserve them for the future.