Behind the Lines 2023

Our annual exhibition of political cartooning.

Location

Lower floor

When

Daily until late 2024

Behind the Lines 2023 showcases the year in political cartoons.

Featuring established and emerging cartoonists from across Australia, this exhibition highlights the significant contribution they make to cultural and political debate through witty, insightful and often poignant satirical drawings, paintings, GIFs and sculptures.

For 2023 our Behind the Lines exhibition theme is 'All Fun and Games', reflecting a year where political party games were being played in parliament and featured in Australia's daily news.

Visit the exhibition online.

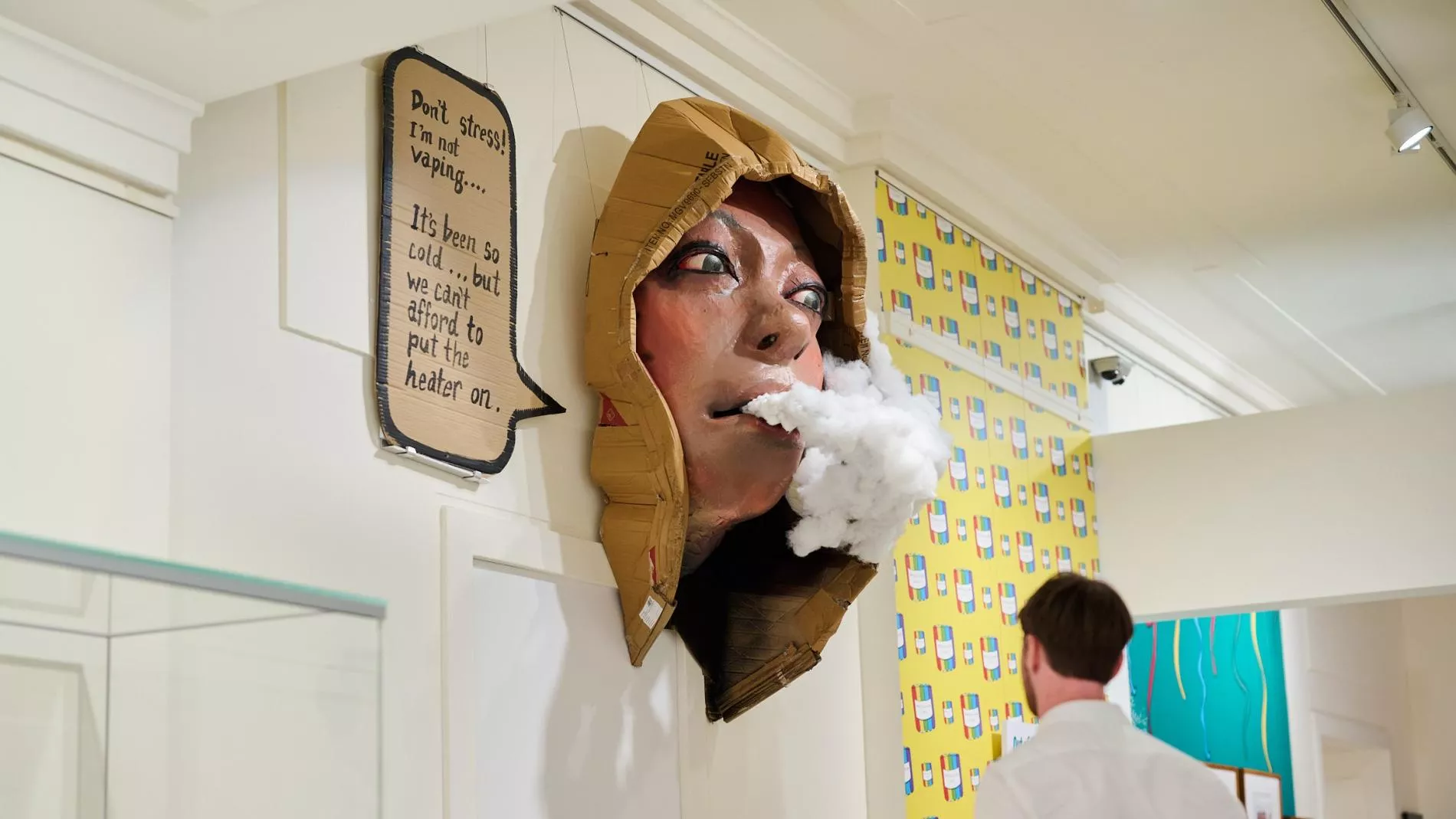

Out of the Frame

This year’s new ‘Out of the Frame’ section explores the way some contemporary political cartoons are jumping off the newspaper and magazine pages and using new and creative formats.

GIFs, sculptures and even puppets enable cartoonists to reach new audiences beyond traditional newspaper readers.

Audio Description

![]()

A selection of cartoons are audio described for visitors who are blind or have low vision. Listen online or book your free ticket to an audio described tour.

Travelling exhibition

In 2024, Behind the Lines will travel to venues around Australia, proudly supported by the National Collecting Institutions Touring and Outreach Program, an Australian Government program aiming to improve access to the national collections for all Australians.

Dates and venues

- Cowra Regional Art Gallery, NSW – 11 February to 17 March 2024

- Old Treasury Building Melbourne, VIC – 24 March to 24 May 2024

- Parramatta Riverside Theatre, NSW – 30 May to 1 July 2024

- Parliament of New South Wales, NSW – 5 July to 2 August 2024

- The Hawke Centre, SA – 4 September to 30 October 2024

Plan your visit

All areas of the exhibition are accessible by wheelchair.

When the exhibition is busy, there may be a lot of people in the hallways where the cartoons are hung.

This can be a popular and busy exhibition.

Some cartoons in the exhibition are moving GIFs.

The cornhole game on the front wall of the exhibition makes sounds and includes flashing lights when played.

Watch a video of some of this year’s featured cartoonists.

Play a food fight-themed game of cornhole or test your knowledge of 2023 news article headlines with a card game.

Large text guides are available.

This exhibition features cartoons that discuss war, violence, racism and death. There are images of smoking.