George Reid: not another boring politician

- DateTue, 18 Feb 2014

‘Bores are in a class of infinite variety. But the worst are those who occupy public time.’ So declared Sir George Reid, Australia’s fourth prime minister, who regarded politics as a battle of wits in more ways than one.

A selection of books from Reid's personal library from can tell us a lot about the modus operandi of a man historian Gavin Souter described as ‘an astute politician often mistaken for a clown’.

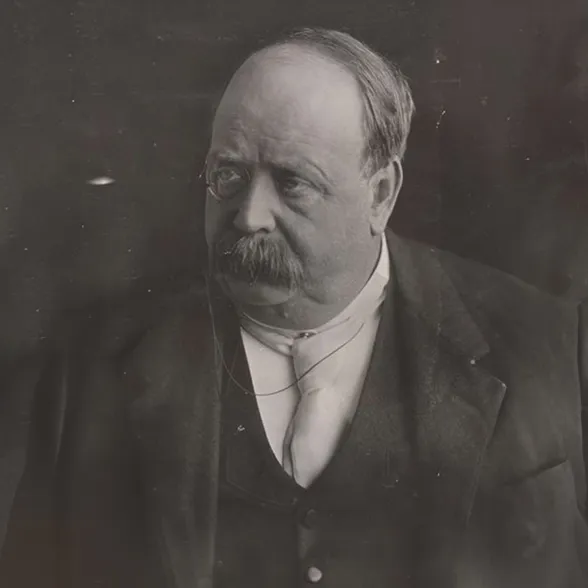

Sir George Reid, who was not at all boring. Credit: National Library of Australia

Reid’s ‘sleepy, lazy good humour’, Souter wrote, masked ‘a wit like a rabbit trap’. For Reid, staying good-natured was a weapon of defence and attack: regardless of the political outcome, he always secured a moral victory. ‘Nothing irritates your opponents more’, he wrote in My Reminiscences. ‘Nothing gives you a better footing with an audience.’ Crowds flocked to hear his speeches, which he peppered with cheeky quips and quotes. He got his ideas from books like Love and Other Nonsense and learned jokes off by heart. Alfred Deakin, who thought him vulgar, nevertheless thought ‘his eloquence remarkable.’

Love and other nonsense, a book of quotations, sayings and advice on love, marriage and the sexes. published by Arthur L Humphreys, London, England, 1909.

Reid’s oratory evolved at the Sydney School of Arts Debating Society. (One of his adversaries was future High Court Justice Richard O’Connor.) He joined the Society after leaving the ‘aimless drudgery’ of school aged 13 and becoming an office clerk. He later attended lectures on metaphysics, logic, moral philosophy and psychology and, when he had a spare moment, also studied law. He was admitted to the Bar in 1879 and in 1880 entered colonial parliament representing East Sydney.

In 1883 Reid turned down a chance as Treasurer to become Minister of Public Instruction. Under his direction, New South Wales’ first high schools and a technical education system were established. He was also responsible for the Bill that eventually provided for degree courses for evening students at the University of Sydney. Like many men of his era and background (his father was a Presbyterian minister) Reid was devoted to self-improvement, and wanted others to reap the benefits as he had done.

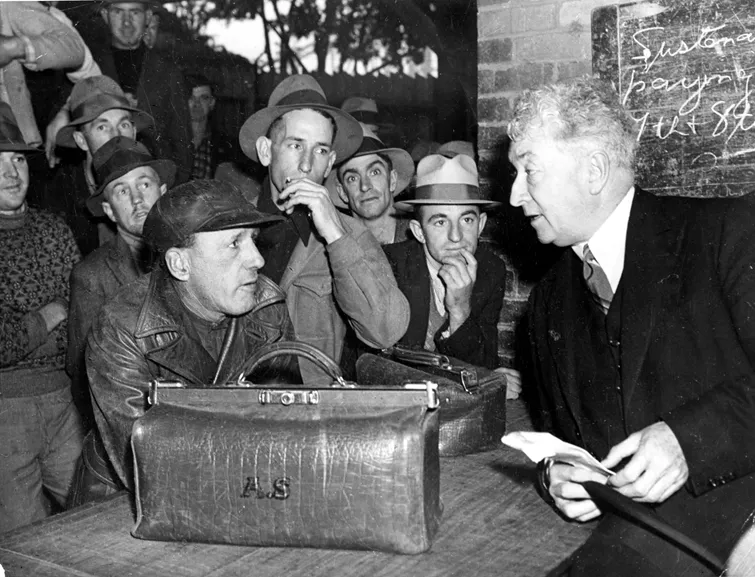

Reid’s books demonstrate that he consciously developed his repartee throughout his career in Australia and the United Kingdom. He probably acquired another book on display, The Charm of Gardens, during his years in London as Australian High Commissioner (1910–1916) and later Member of the House of Commons (1916–1918). His interest in progressive liberal philosophy is demonstrated in An American Bible, a selection of writings by politicians, poets and philosophers including Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman. It is likely he drew inspiration from these essays during his 1917–1918 lecture tour of the United States to promote the war effort. ‘When the ears of an audience are tickled’, he wrote, ‘the approaches to its intelligence and sympathy become easier.’

Reid also loved historical fiction, and his copies of such works as William Thackeray’s The History of Henry Esmond and The Four Georges (about four Hanoverian kings of Britain) helped him understand times and places beyond his experience. For example, his notes in Kathleen Watson’s Later Litanies suggest he drew upon her tale of an Antarctic explorer for a speech he made in 1914 to honour Dr Douglas Mawson, leader of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition. Mawson had named a newly-discovered glacier after Reid, but since Reid would never encounter the ice first-hand, it seems he used others’ insights to enhance his expertise.

George Reid’s stout body belied his light heart, and he was reportedly the only politician to receive an ovation from the crowd at the Commonwealth inauguration ceremony in Sydney on 1 January 1901. Reid’s books reveal something of the man who flummoxed political rivals by offering them lollies and who, upon receiving a KCMG in 1909, insisted the initials stood for ‘Kindly Call Me George’.

Can you think of any other prime minister like him?