Exploring the War Precautions Act

- DateThu, 23 Apr 2015

'Everything must be made to bend in wartime.'

In April 1915, Australian soldiers were landing at Gallipoli, launching a campaign and a piece of our national history and identity. At home, however, the politicians who sent them to war weren’t talking about the landing, or the conduct of the war, in parliament. Debate was heated on a piece of controversial legislation which still has resonance a century later; the War Precautions Act.

The War Precautions Act was passed in October 1914 by the newly elected Labor government led by Andrew Fisher. Under the Act, the federal government could, by regulation, exercise powers relating to the war effort, in a wide range of areas over which it had not previously had any authority. Regulations did not and do not require the approval of Parliament. Some of the powers granted by the Act included issuing and refusal of passports, interning of ‘enemy aliens’ and, most controversially, censorship of newspapers and letters to remove anything the government deemed contrary to the war effort. Use of these powers, especially censorship, increased as the war went on. It sparked a debate Australians are still having today – in times of war and crisis, does the government have the right to curtail personal freedoms in the name of safety?

The Act had been passed by the time of the Gallipoli landings, but a second Act was introduced in April 1915. Fifteen thousand miles from the front, Australia’s political leaders debated whether or not the war effort deserved such drastic measures at home. The government’s case was prosecuted mainly by Billy Hughes, who was Attorney-General and who would be Prime Minister before the year was out. Opposition to the bill came not from the Liberals, who under Joseph Cook were the formal Opposition in Parliament, but from Fisher and Hughes’ own back bench. One of the most vocal opponents was Labor MP Frank Anstey. Anstey was a passionate socialist who had opposed the war from the beginning, a stance that, at the beginning of the war, made him rather unpopular. Anstey was a mentor of future Prime Minister John Curtin, and would go on to be a deputy leader of the party and a minister in the Scullin government. But at this point of his career, Anstey was a backbencher determined to make his point.

On 28 April 1915, three days after Gallipoli, hansard records show that Anstey made the following speech in the House of Representatives:

'I do not think Parliament is doing its duty. The Governor-General is to make regulations to secure the public safety, and the military authorities are to be the judges of what is public safety. They will be able to suppress freedom of speech and the liberty of the press; and if, under these powers, the military authorities can suppress individual liberty in that way, may not the Government also exorcise these powers during the currency of the war to protect the general public against the robbers who exploit them within our borders? If they can suppress the right of a man to express his opinion, may they not utilize the same power against those people referred to by the honourable member for Wannon, who unjustly raised the price of fodder? But we do not do that, and Parliament has no intention of doing it.

Soldiers in Rabaul write letters to me to protest against the iniquities there; but their letters are censored, and I must receive them by hand. So a soldier gives a letter to some stoker on a ship, and asks him to forward it to me; but if those men do such a thing after this Bill is passed, they will be liable to be shot.'

He went on to say:

'If anyone can show me that dangers menace us, I am prepared to give up the right of free speech, and of a free press – to give up every individual right – in order to maintain the existence of the country; but I must be shown that it is necessary to take steps far beyond those taken by any country actively engaged in the war. We are being simply swept away by one vast tide that is overwhelming our ideas of human rights and liberties; and I refuse to let it be thought for one moment that I can give my adherence to such a proposal.'

Another prominent opponent of the Bill was Edward Riley, another Labor MP. Riley was very concerned about the level of authority the Act, and the regulations under it, would place in the hands of the military. Further, Riley objected to the provisions in the bill for the death penalty to be used by military authorities; Australia at the time still had capital punishment, but never before had the authority to execute an offender rested with anyone other than the civil courts. Riley said, on 28 April:

'The Ministry must be very careful how it hands over the civil rights of the people to military control and the judgments of courts martial. This Bill is giving over to the military authorities of the country the rights of the people. Those who have read the early history of Australia know that when the military power ruled this country there was nothing but stagnation and tyranny, and it was only when civil Courts were established, and people were no longer at the mercy of the courts martial that there was any progress. I cannot for the life of me understand why a person charged under this measure cannot be tried in a civil Court. We are a civilized community, with the whole machinery of the law ready to be put into operation at any moment, yet this Bill proposes to take certain civil offenders away from the civil Courts and hand them over to a military Court which is given power to impose the sentence of death. To my mind, that is giving altogether too much power to the military authorities. I can understand them having that power on the field of battle, where they have to deal with large bodies of men, but not in Australia, where we are surrounded by all the machinery of the civil law. I desire to know what is in the minds of the Government that they should desire to take away the civil rights of any individual and hand them over to a military Court.

The civil Courts should be clothed with power to deal with all actions against civilians that may arise out of the passing of this Bill. Another reason why I am loth to agree to this Bill is that we are handing away the right of trial by jury, which is the keystone of the liberties contained in Magna Charta. Further than that, I see no necessity for these extreme powers. We have control of the Pacific and the whole of the wireless stations, and the postal, telephone, and telegraphic services are under the administration of the Commonwealth Government, so that Australia is perfectly safe.'

Another prominent opponent of the Bill was Edward Riley, another Labor MP. Riley was very concerned about the level of authority the Act, and the regulations under it, would place in the hands of the military. Further, Riley objected to the provisions in the bill for the death penalty to be used by military authorities; Australia at the time still had capital punishment, but never before had the authority to execute an offender rested with anyone other than the civil courts. Riley said, on 28 April:

'The Ministry must be very careful how it hands over the civil rights of the people to military control and the judgments of courts martial. This Bill is giving over to the military authorities of the country the rights of the people. Those who have read the early history of Australia know that when the military power ruled this country there was nothing but stagnation and tyranny, and it was only when civil Courts were established, and people were no longer at the mercy of the courts martial that there was any progress. I cannot for the life of me understand why a person charged under this measure cannot be tried in a civil Court. We are a civilized community, with the whole machinery of the law ready to be put into operation at any moment, yet this Bill proposes to take certain civil offenders away from the civil Courts and hand them over to a military Court which is given power to impose the sentence of death. To my mind, that is giving altogether too much power to the military authorities. I can understand them having that power on the field of battle, where they have to deal with large bodies of men, but not in Australia, where we are surrounded by all the machinery of the civil law. I desire to know what is in the minds of the Government that they should desire to take away the civil rights of any individual and hand them over to a military Court.

The civil Courts should be clothed with power to deal with all actions against civilians that may arise out of the passing of this Bill. Another reason why I am loth to agree to this Bill is that we are handing away the right of trial by jury, which is the keystone of the liberties contained in Magna Charta. Further than that, I see no necessity for these extreme powers. We have control of the Pacific and the whole of the wireless stations, and the postal, telephone, and telegraphic services are under the administration of the Commonwealth Government, so that Australia is perfectly safe.'

For its part, the Fisher ministry defended the powers as necessary, with Hughes’ speeches in support of the bill showing all the rhetoric and passion for which he was famed. Hughes said the bill was necessary to protect Australia from the enemy, and that nothing was illegal under the act that wasn’t already an offence. Hughes maintained that Australia was under a grave threat and drastic measures were needed. On this same day of debate, Hughes said:

'It will never be used except as a last resort in a desperate emergency, and this may be very near at hand. We may look abroad. The honourable member for Darwin said that the war is 12,000 miles away. That is true; but why? The war is 12,000 miles away because every day we live thousands of men die horrible deaths and endure untold sufferings to keep it away. Some of my honourable friends speak as though we were men living in a glass case, over whom Providence watched daily and hourly, and from the beginning had decreed that we alone amongst all the nations of the earth were to be free from trouble, distress, and privation. But we live sheltered under the glorious valour of our soldiers, who, by prodigies of bravery, have kept the foe at bay. But no one is to say when these tremendous pent-up forces of destruction may burst the barrier which now hedges them about, and then the war will not be 12,000 miles away, but at our very doors. Then we shall hear no voice croaking in the marshes about the stern edge of military law, but rather we shall regret with all the power we have in us, and with all the bitterness that comes from unavailing sorrow, that we were not more prepared to meet the ruthless invader.'

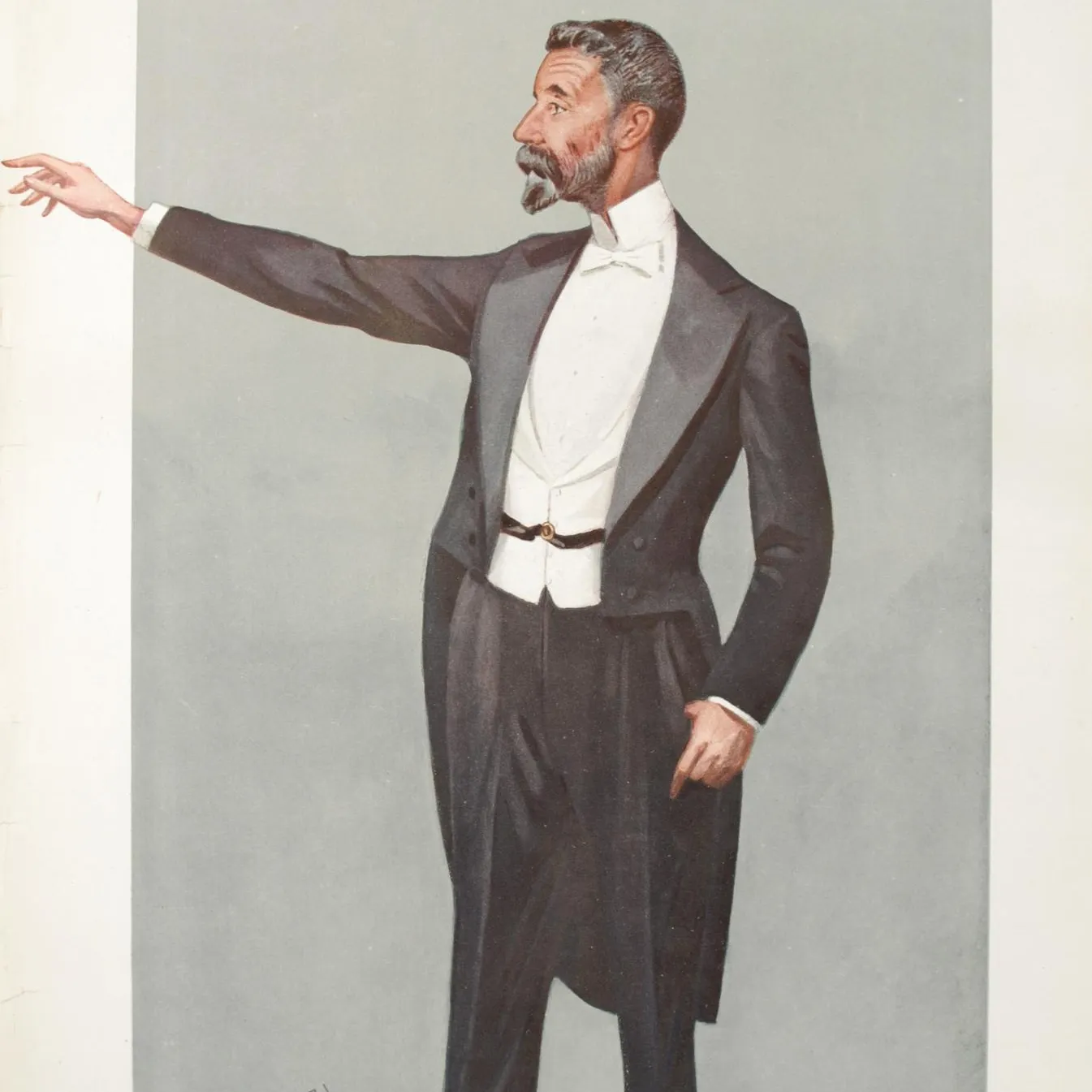

The Cook Opposition gave the bill its full support. On 23 April, Cook said:

'Everything must be made to bend in war time to the supreme purpose of making the State safe... I simply say to the Government, “Good luck to you; take your Bill, and do what seems good.”'

It seems Cook was as determined to pass the bill as Hughes. Cook, a Methodist lay preacher, saw the war as a mission from God to defeat German tyranny, and his diary records his obsession with winning the war at all costs. So, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that he supported a bill designed to aid the war effort, even at the cost of civil liberties.

The bill was passed by the House on the evening of 29 April 29. Earlier that day, Prime Minister Fisher had announced to the House that Australian troops had landed at Gallipoli.