A 'follitical' liability?

- DateFri, 22 Nov 2013

Even to those unfamiliar with the luminaries of early Australian federal politics, photographs of the era’s protagonists reveal an obvious and unmistakable distinction from later generations of politicians.

Take a look at the portraits of our first few prime ministers. An unfamiliar observer will note that the 'face' of Australian politics has undergone a fundamental image make-over, a transformation marked by an obvious lack of facial hair. Most of us are well acquainted with the likeness of George Reid’s walrus-like moustache, with Alfred Deakin’s thick, yet impeccably groomed whiskers and Andrew Fisher’s voluptuously horizontal mouth-brow. By the time the roaring twenties had swept the glabrous Stanley Bruce to power facial hair had become a political liability, every politician was acutely aware of the 'follitics' of personal grooming, a conspicuously clean-shaven look became the new political status quo, the legacy of which extends to our own time.

Nowadays, beard-o-philes the nation over lament the sacrosanct shaving of facial hair from our political culture. One annual event more than any other causes us to reflect on this fact: Movember. From its humble beginning in Melbourne in 2003, Movember is now a world-wide event which encourages men (Mo-Bros) to grow moustaches during the month of November to raise awareness of testicular cancer and mental health issues. It’s safe to say the prevalence of facial hair in Australian culture has experienced significant 're-growth' in the last decade, though a century ago a well-cultivated beard was considered a prerequisite among our political elite. No doubt their sentimental veneration of mutton-chops, moustaches and beards stems from Victorian Britain. In the second half of the 19th century respectable Englishmen cultivated long flowing whiskers. The enthusiasm for facial hair had spread from the margins of society; no longer was it exclusively associated with radicalism (artists and Chartists), facial hair had entered the popular mainstream. Cultural historians have argued that these changing attitudes were part of a broader, more decisive reformulation of masculinity in the mid-Victorian era. Multiple theories abound, from the influence of heroic and hirsute soldiers returning from the Crimean War to the pseudo-scientific 'miasmatic theory', which held that a long flowing beard could act as a kind of natural filter for noxious air, thus preventing airborne diseases.

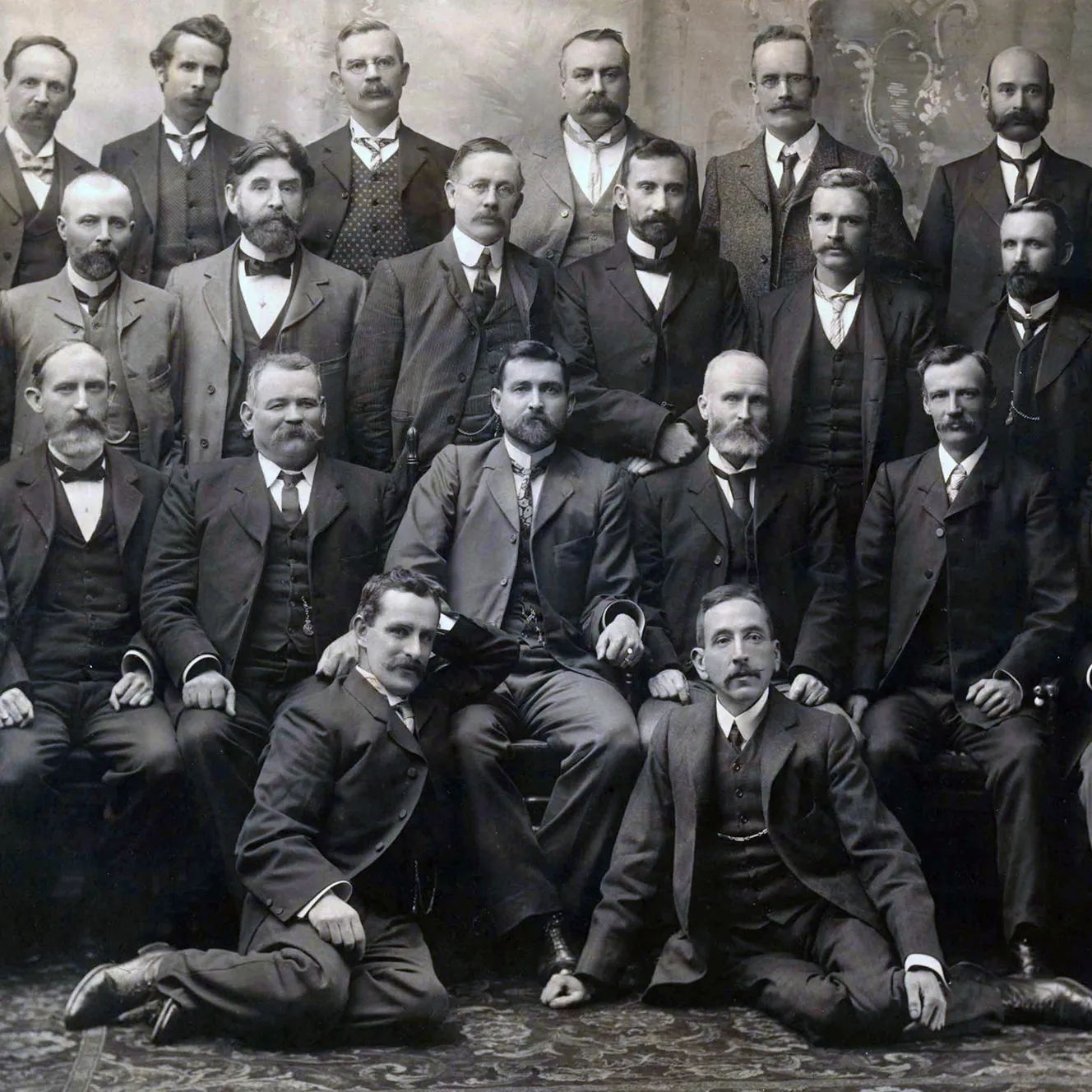

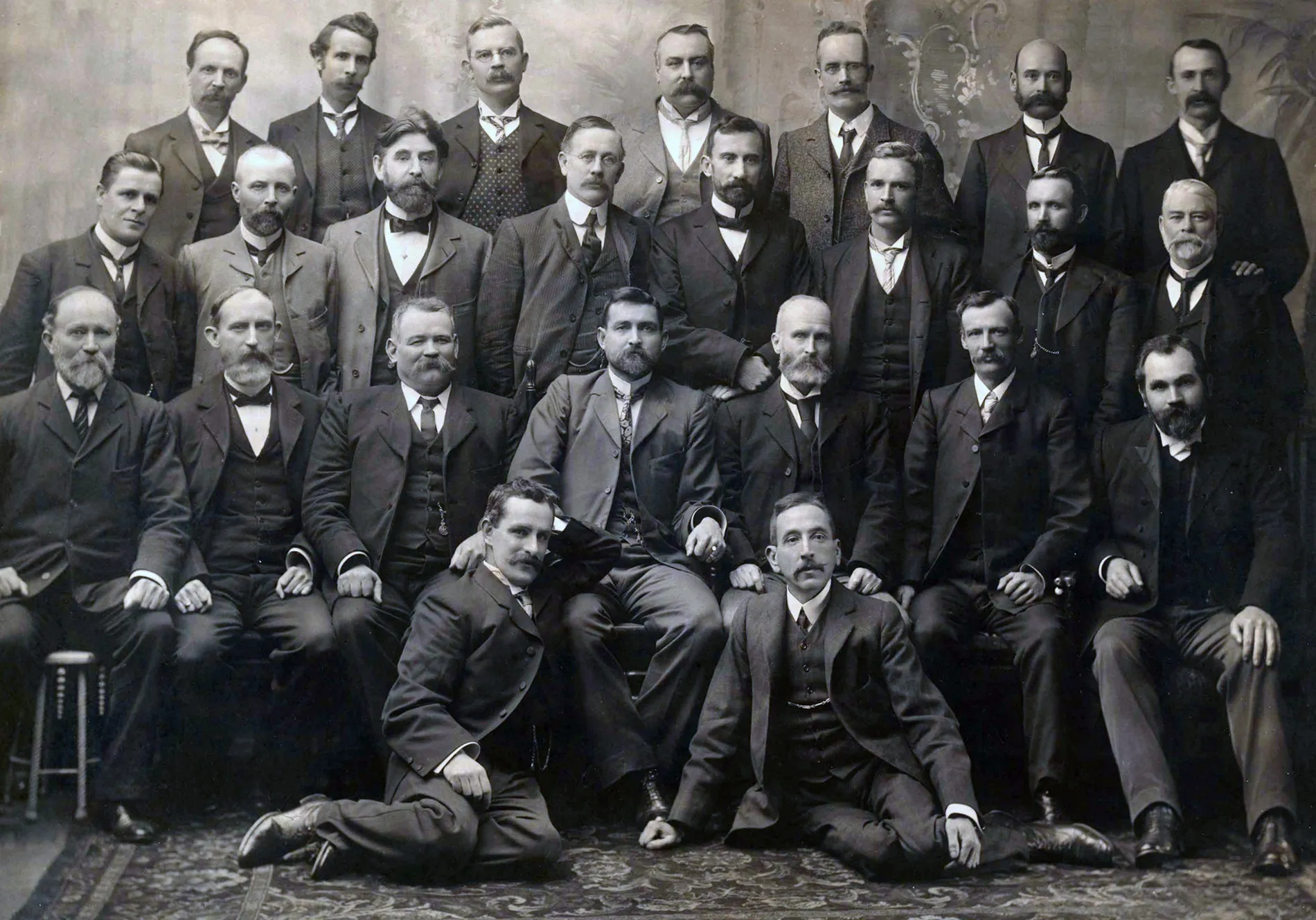

It was widely believed that beards were fundamental to masculinity, by serving as a physical symbol of masculine qualities—particularly independence, hardiness and decisiveness. In a rapidly industrialising era these values were increasingly strained, as perceptions of manhood were reconciled with new types of work that were considered honorable and appropriate for men. Politics however, remained the dominion of men. Masculine customs were reinvented in the political arena and cultivated beards served a strategic purpose for implacable foes. Somber politicians could engage their opponents in verbal combat, whilst their free flowing whiskers served to reinforce a sense of masculine authority - that one was 'man enough' for the job. By concealing emotions, these stoic, poker-faced MPs sought to unnerve their adversaries, the presence of astutely cultivated facial plumage served both to intimidate rivals and conceal an insecure countenance. This culture of masculinity retained traction in the immediate post-Federation era for Australian politicians (perhaps with the exception of Edmund Barton). The group portrait of federal Labor MPs elected at the inaugural 1901 election is a case in point, with all but one member (David Watkins) sporting vigorous growth. The prominence of beards during this era has been used as a definitive form of visual shorthand for the masculine character of politics, an equivalent comparison remains to be seen in our own time.

Group photograph of all Federal Labour Party MPs elected at the inaugural 1901 election, including Watson, Andrew Fisher, Billy Hughes, and Frank Tudor.