A closer look at the Coat of Arms in the House of Representatives

When we restored the House of Representatives chamber in 2023, we unearthed surprising stories from Old Parliament House's past.

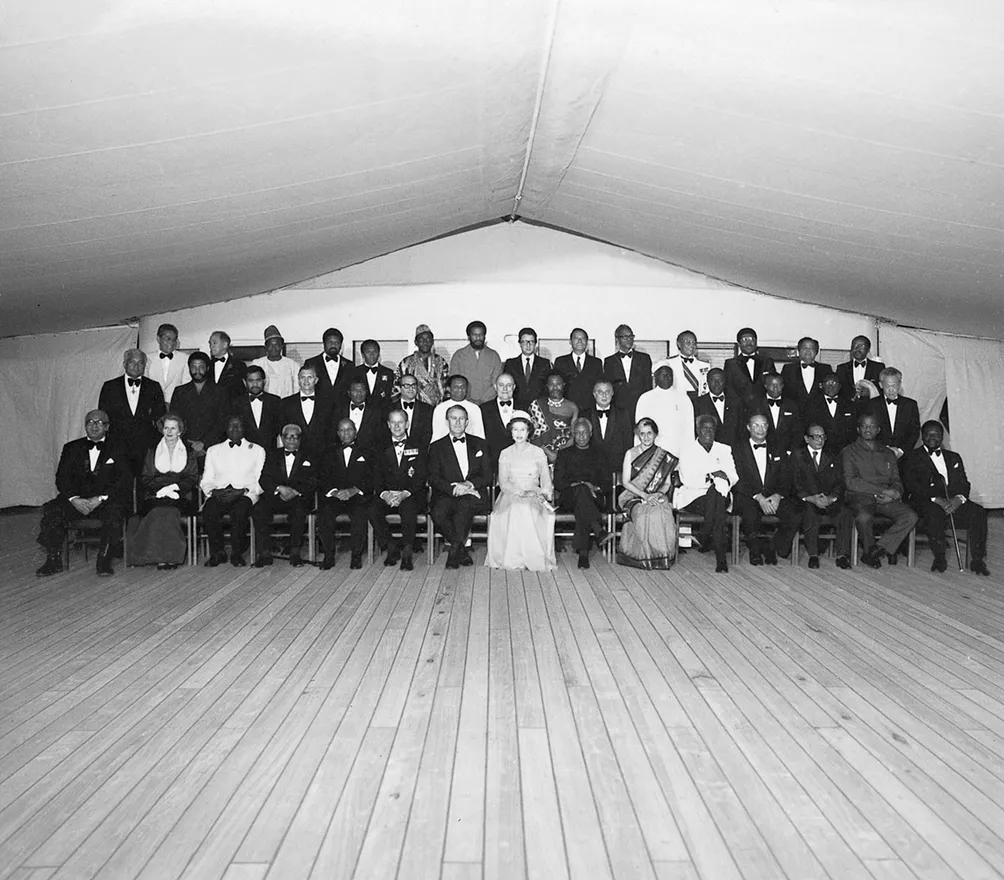

Remembering Elizabeth II in the halls of Old Parliament House

The life and reign of Elizabeth II is closely connected to the history of Old Parliament House.

Just add unicorns: celebratory coronation arches from London to Canberra

A royal tour is filled with grandeur and glamour; there’s gowns, tiaras, fancy state balls, and sometimes, even unicorns. Read on to discover how Canberra welcomed not only the Queen, but also mystical beasts from another land.

7 people you (maybe) didn’t know ran for parliament

Numerous actors, musicians and sporting stars have a 'political career' subheading on their Wikipedia page, but some have been more successful than others.

A seat at the table

In Australia, the ability to vote reflects a longer story of democracy.

The rise of bee activism – how these humble insects have inspired a mass movement

In recent years, concern for the health of honeybees has sparked a rise in bee activism, helping to shine a spotlight on the challenges facing the world's bee population.

What bees can teach us about democracy

What do honeybees and a House of Parliament have in common?

Showing up, learning and yarning – Dhani Gilbert on Healing Country

The theme of NAIDOC Week 2021 is Heal Country.

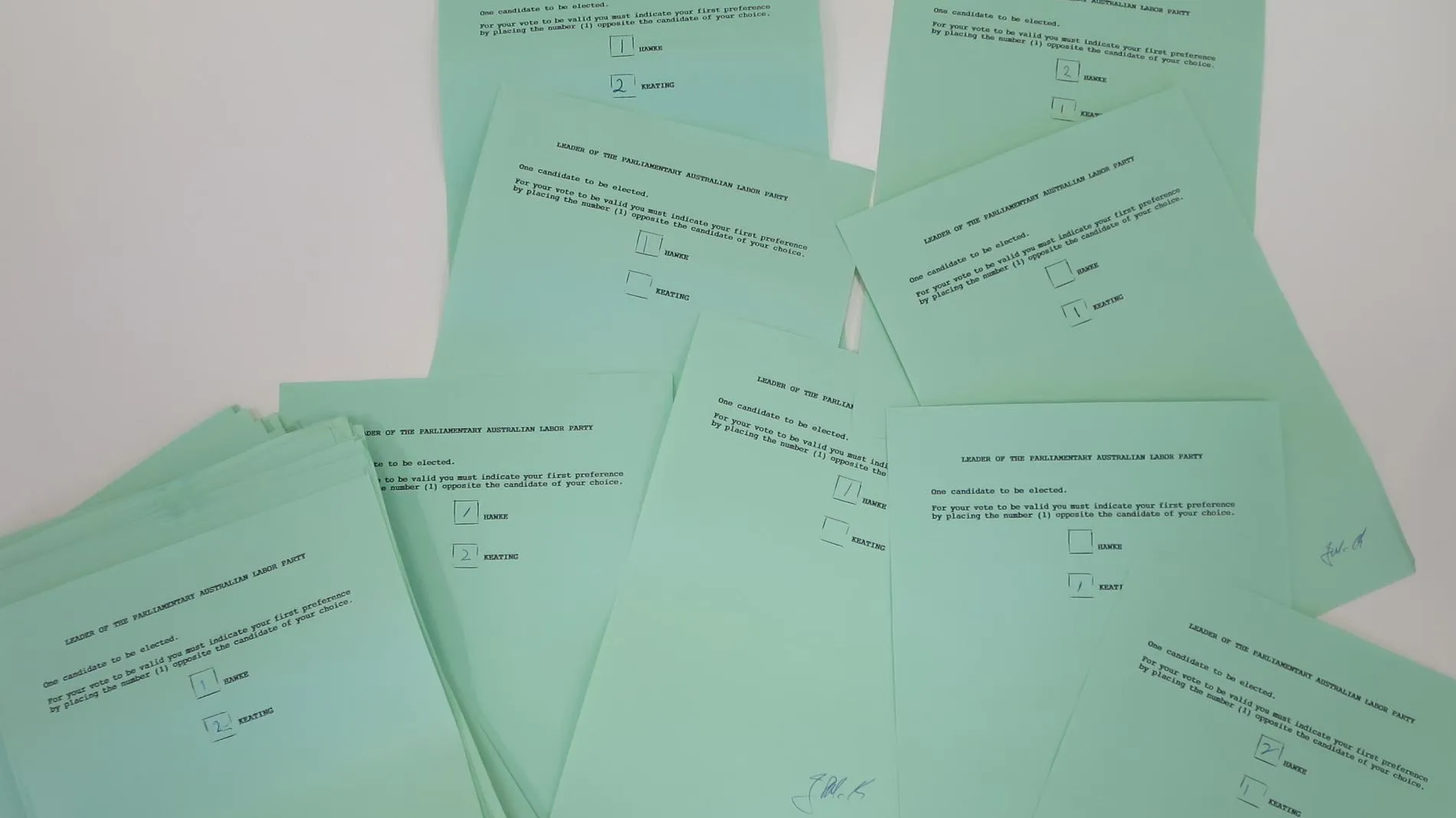

How are party leaders chosen?

In June 2021, the National Party replaced its leader Michael McCormack with former leader Barnaby Joyce, an unexpected change in Deputy Prime Minister.

Zines from the Refugee Art Project

Sydney-based artist, musician and academic Safdar Ahmed has been facilitating the making of zines that share the art and stories of people incarcerated in the Villawood detention centre.

From tulips to trenches: comings and goings in the Old Parliament House Gardens

Old Parliament House is flanked by two stunning rose gardens – the House of Representatives and the Senate Gardens.

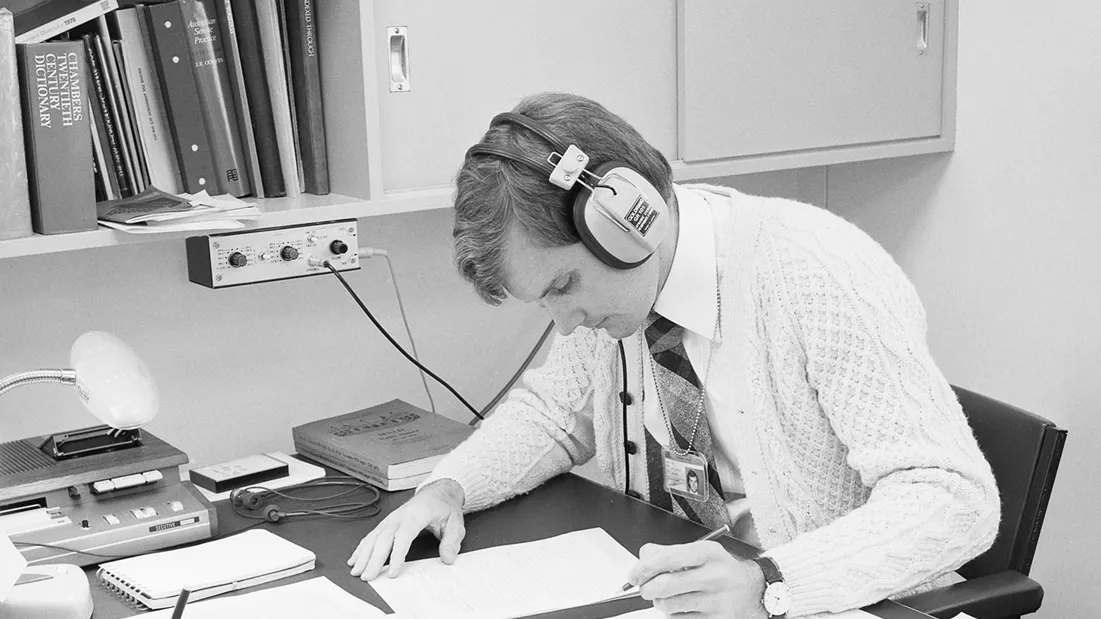

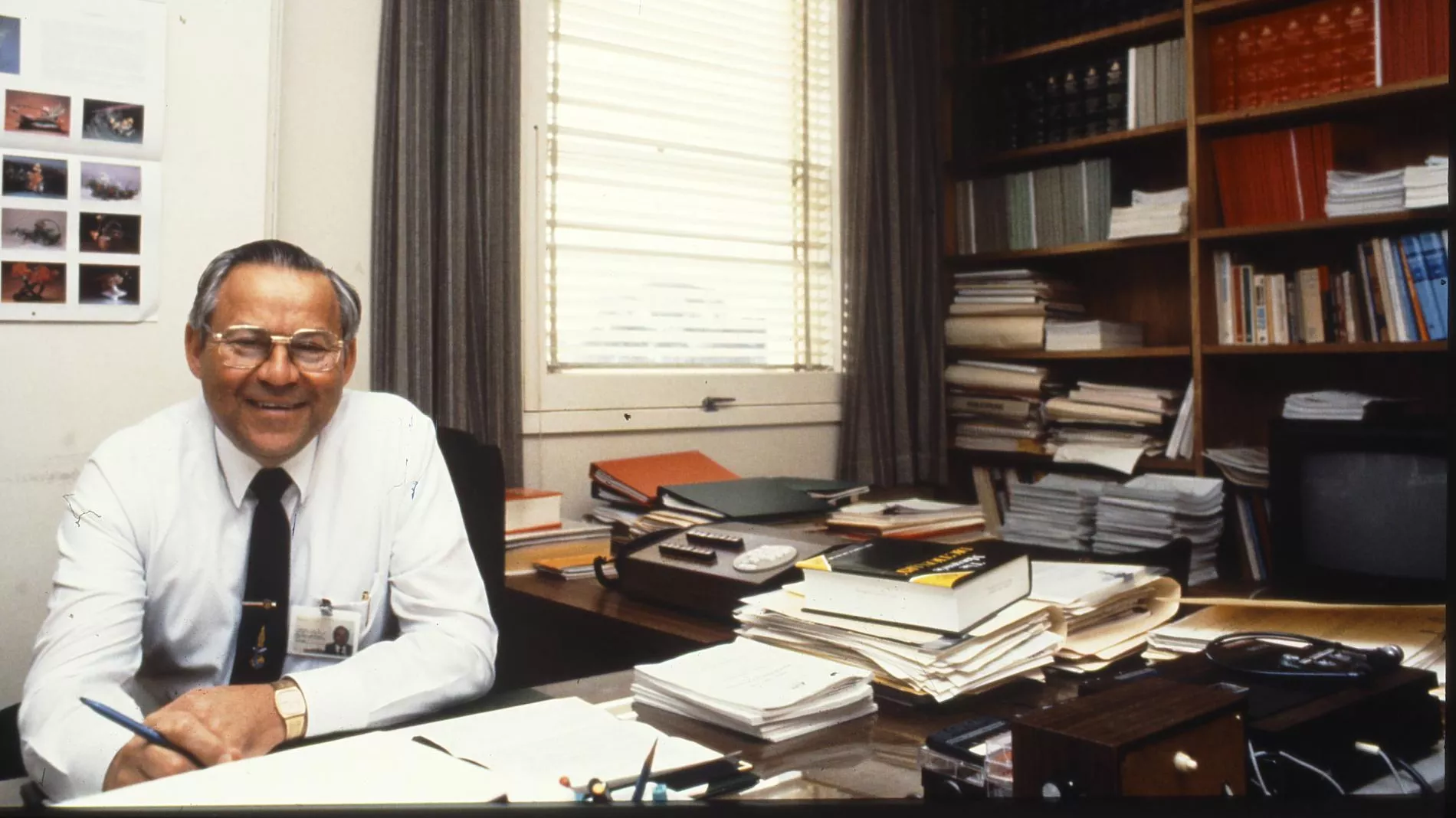

Sixty years of service: John Campbell

In 1960, a young man in Brisbane noticed a newspaper advertisement for a position of Hansard reporter at Parliament House, Canberra.

Is it compulsory to like compulsory voting?

There are good arguments, sound, solid, democratic arguments, both for and against compulsory voting.

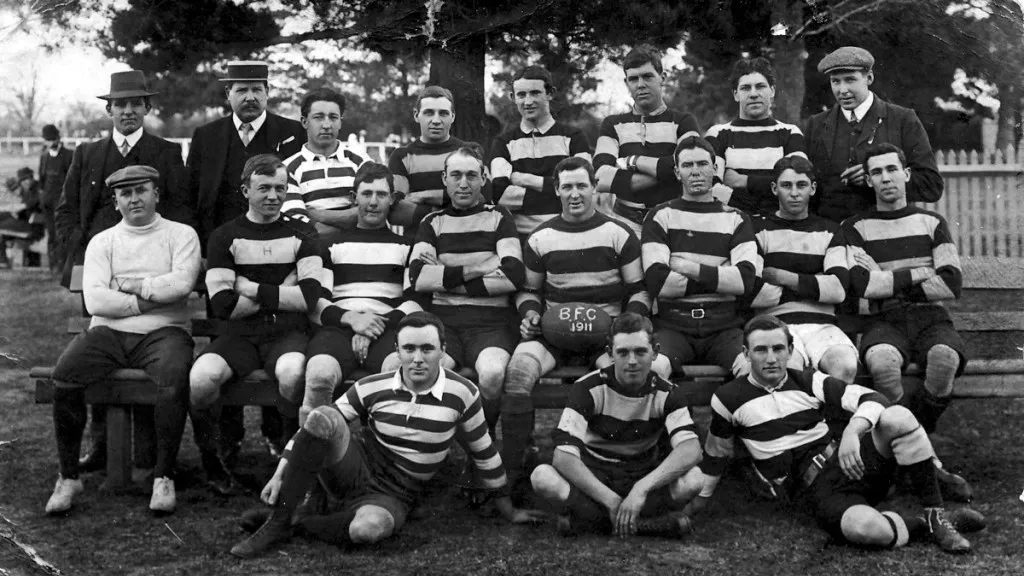

Political football

There are connections between footy and federal parliament stretching back over 100 years.

Reflections of Bob Hawke in Old Parliament House

As Prime Minister, Bob Hawke served five years in the Old Parliament House and three in the new.

What is a vote of no confidence?

Many Australians follow British politics, because of the ties between the two countries.

The strange provenance of the Fairfax collection

Provenance relates to the origins of an object.

A doctor in the house? Five doctors who served in the Commonwealth Parliament

In 2018, Dr Kerryn Phelps was officially sworn in as the Member for Wentworth in the House of Representatives.

Leadership spills plague Australian politics, but what does our system protect us from?

Political leadership in Australia has been characterised by instability and rapid change since the Howard government fell in 2007.

Australia vs America – midterm elections and their influence

Halfway through a presidential term in the United States, voters go to the polls for 'midterm elections'. How is this different from Australia?

What is a redistribution?

At least once every seven years, the Australian Electoral Commission has to reassess and redraw the boundaries of a state's federal House of Representatives seats.

What does a state governor do?

Every state has a governor representing the Crown, but what do they actually do? And who gets to be one?

Agitators, suffragettes and spies: 7 women you should know

Seven Australian women outside politics.

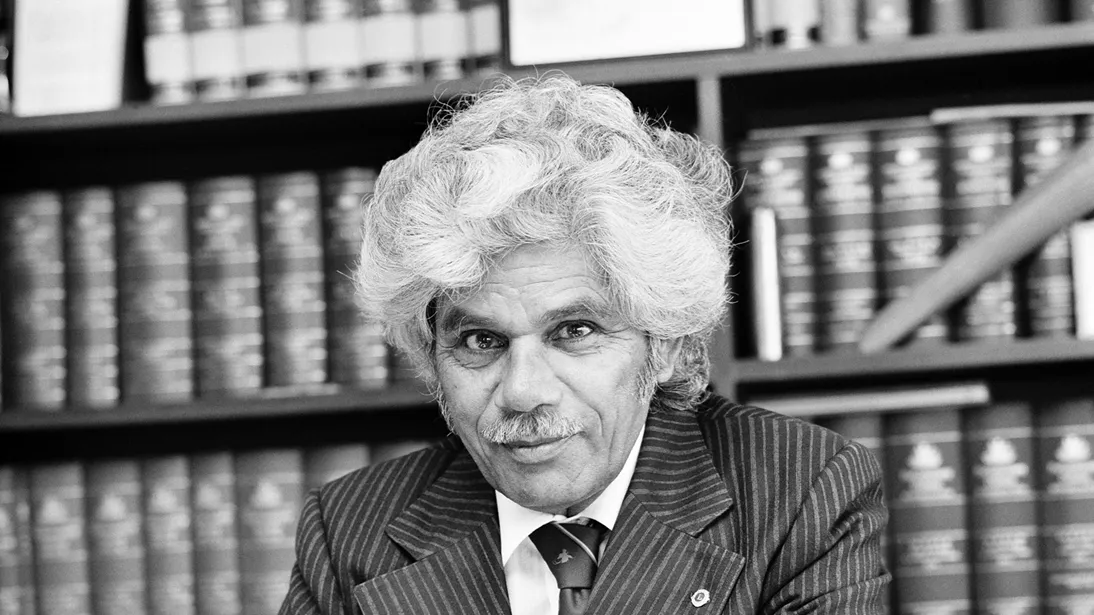

Lionel Rose's world championship 50 years on

In 1968, Lionel Rose became the first Aboriginal Australian to win a world championship.

Red, white and blue: the Australian flag

Australian National Flag Day is observed on 3 September.

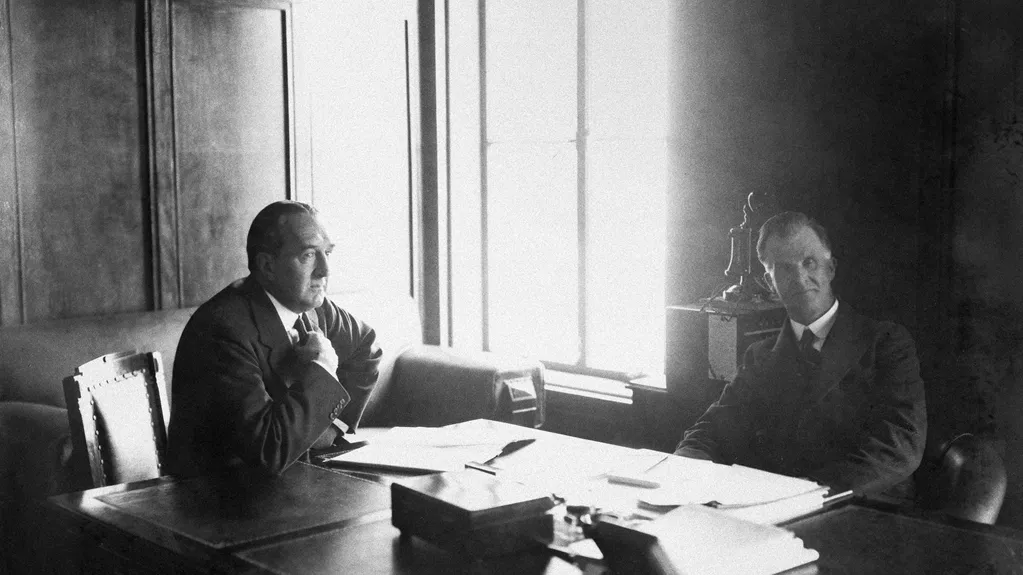

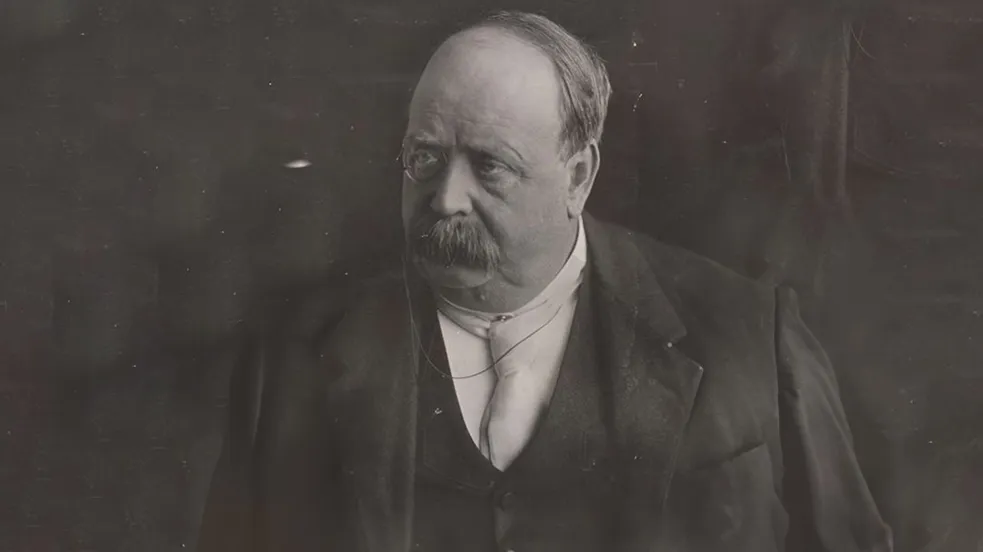

Arthur Calwell and the gift of immigration

When Arthur Calwell addressed parliament as the first Australian Minister for Immigration on 2 August 1945, Australia was still at war.

A voice from the past

This speech recording by Stanley Melbourne Bruce was added to the Museum’s collection in 2017.

Free votes: a quick explainer

It's tough to be a politician. You are called upon to represent the community that elected you, but you're also called upon to follow a party line, and support whoever your party's leader is.

How often should we have an election – every three years or every four?

Does it ever feel like we've just got over the last election before the next one looms?

90-year-old souvenirs for a 90-year-old building

Old Parliament House turned 90 in 2017 and so did the thousands of souvenirs manufactured for the opening of the building by the Duke of York.

The Prime Minister’s seat: a case study in sleuthing

Despite having only seen a small amount of the BBC’s Sherlock, I’ve always been a fan of detective fiction, especially the gentleman from Baker Street.

Young people and the right to vote: Some exceptions to the rule

On 16 March 1973 the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1973 gave all Australians aged 18 years or older the right to vote. The first federal election at which all 18-year-olds could vote was held in May 1974.

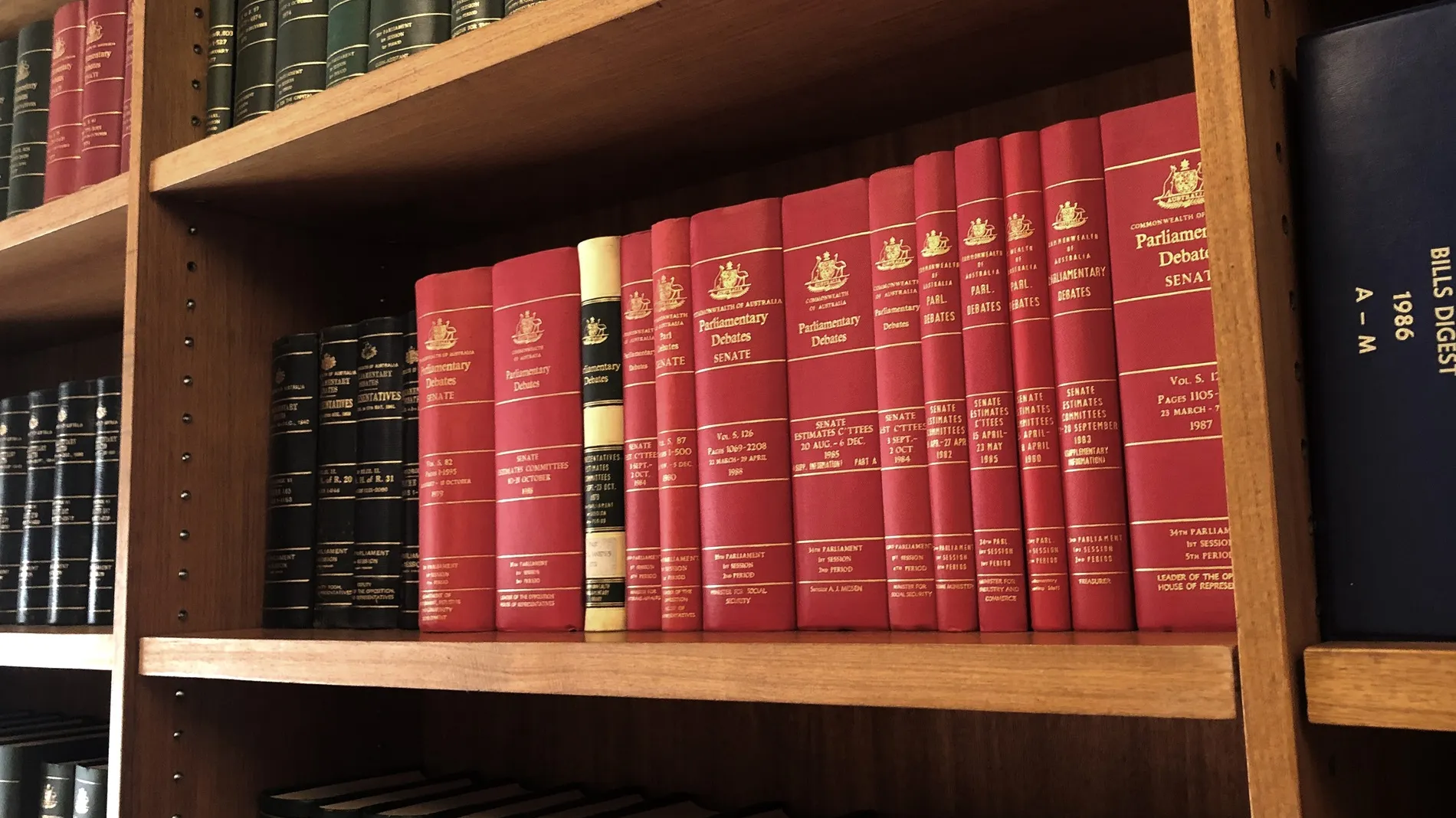

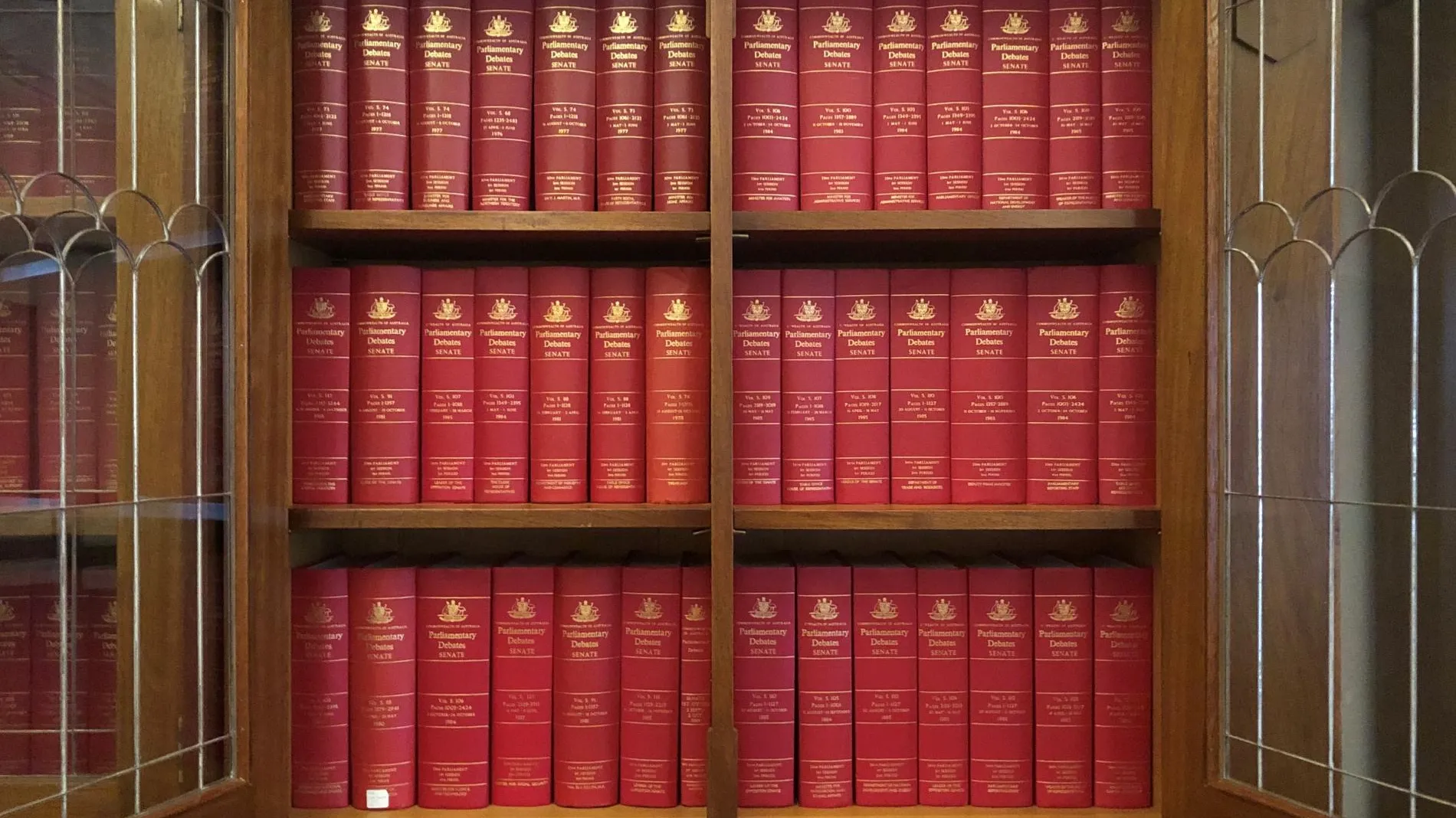

On Hansard

Hansard is testimony, in black and white, to our functioning federal parliamentary democracy - for all its strengths and weaknesses, its brilliance and tawdriness and its immense unending drama.

Donald Grant – from gaoled Wobbly to elected Senator

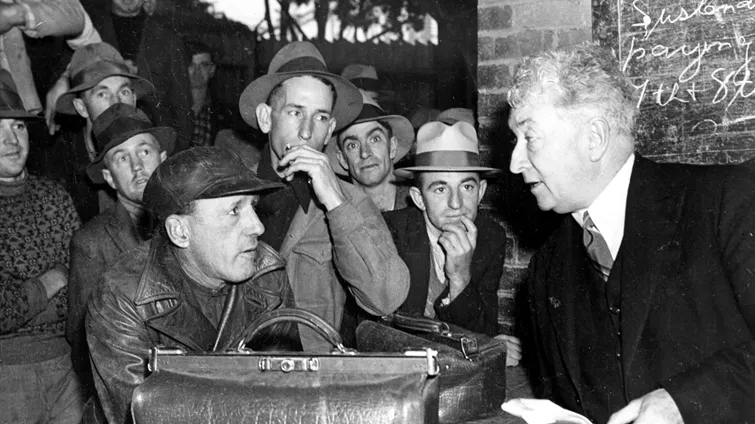

Of the twelve members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) sentenced in 1916 for conspiracy, none is more fascinating than Donald MacLellan Grant.

The Sydney Twelve — treason, conspiracy and conscription in Australia 1916

The ‘Sydney Twelve’ were members of an organisation known as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) who were arrested in Sydney on 23 September 1916 and charged with ‘treason felony’.

The Denmans in British Australia: cultured and courteous with nothing to do

Australia today is not a republic but its culture is in many respects republican.

On This Day: a plot to kill Harold Holt?

After waiting six days outside Parliament House for Prime Minister Harold Holt to get back from Melbourne, Nedeljko Gajic decided to return to Sydney to look for work.

An Australian guide to American elections

In a speech to the National Press Club, the outgoing US Ambassador to Australia, John Berry, outlined some of the differences of democracy in both countries.

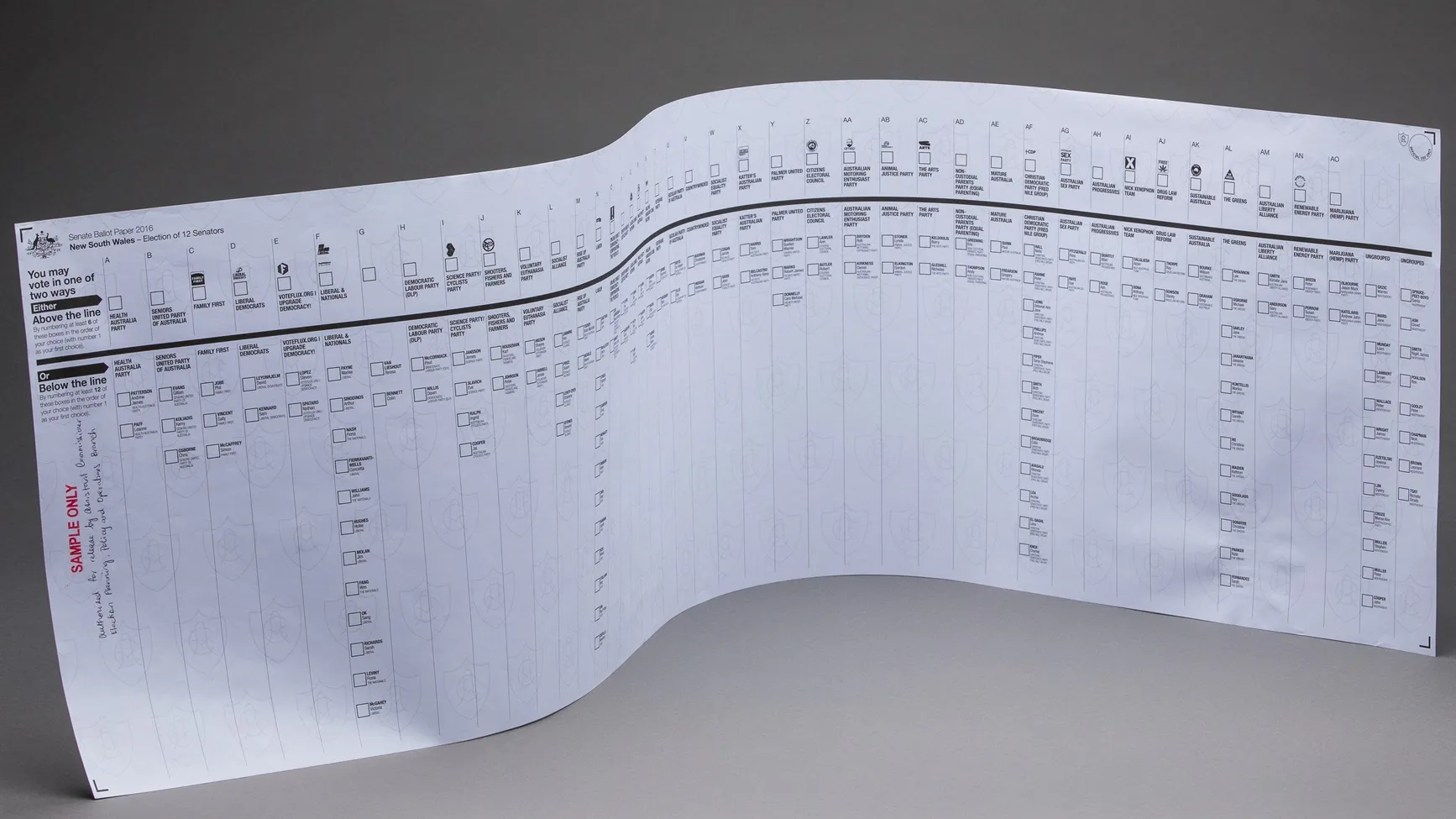

On a Knife-Edge: Six other times Australia’s elections were down to the wire

It took more than a week after the polling day for the result of the 2016 federal election to be declared, with many seats initially too close to call.

Artists and activists: The Ongoing Adventures of X and Ray

Lin Onus, together with his non-Indigenous collaborator Michael Eather, and his son Tiriki, have produced a series of remarkable artworks, The Ongoing Adventures of X and Ray.

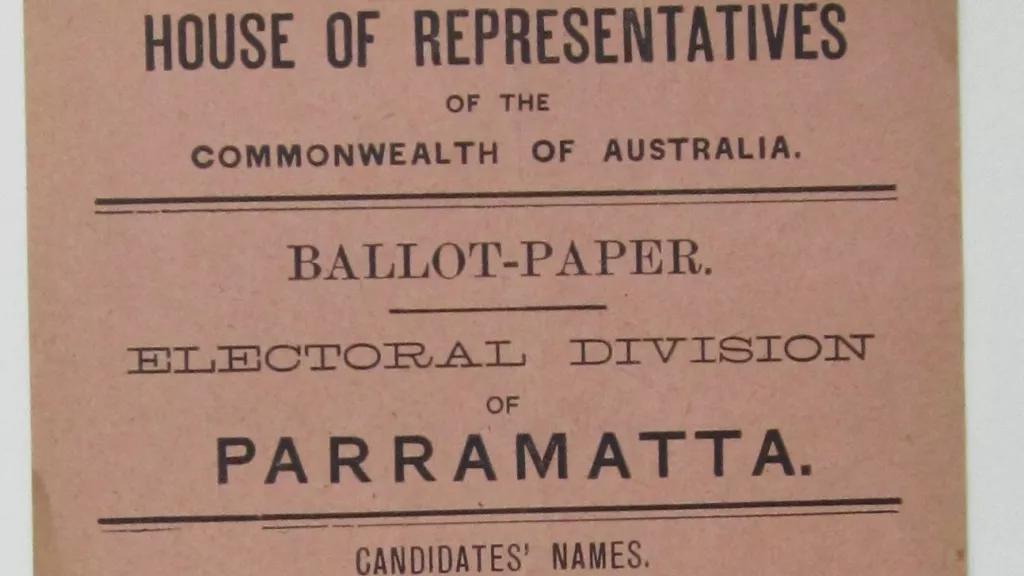

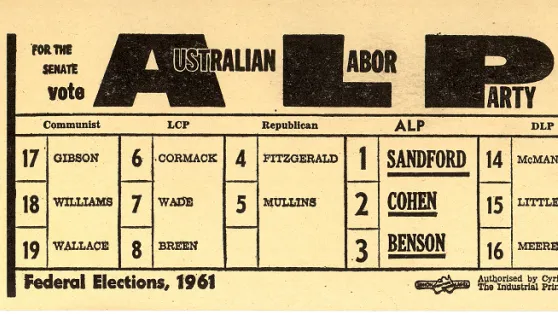

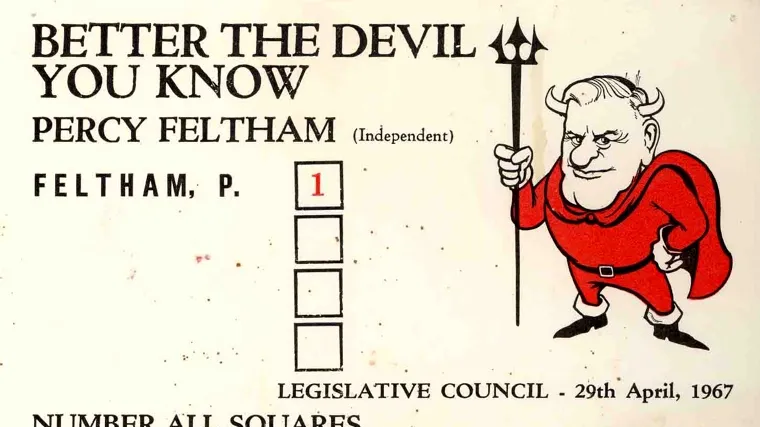

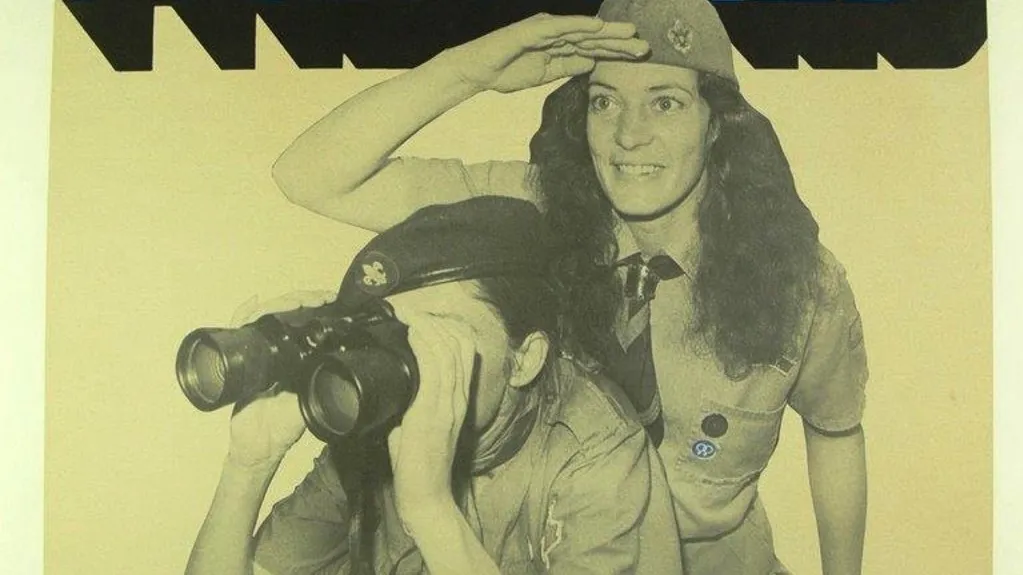

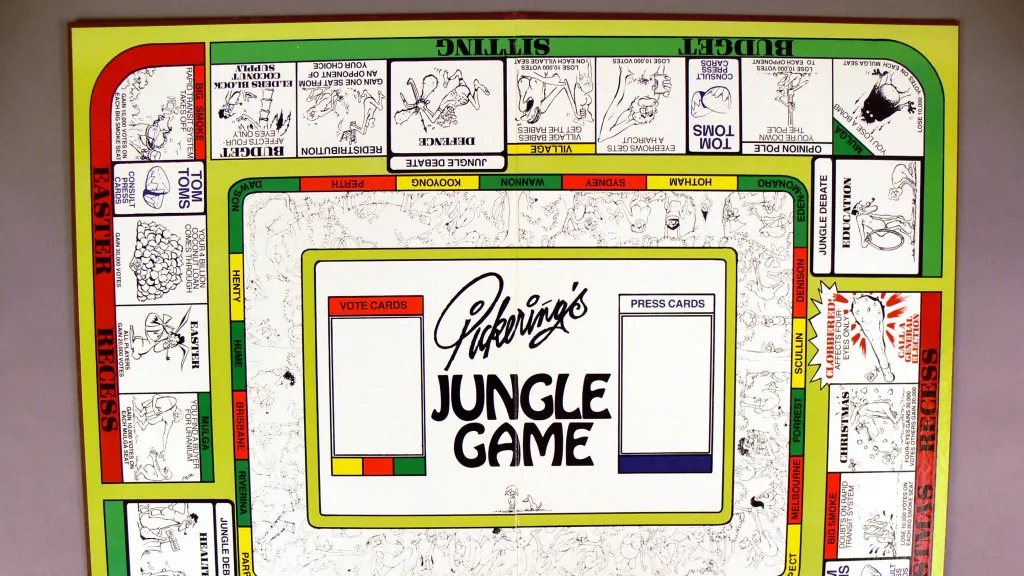

On Paper: some election ephemera

As an election campaign draws to a close, most Australians can look forward to being handed dozens of pieces of paper while queuing to vote.

On this day: a Catholic forgives

But I say to you: Love your enemies. Do good to those who hate you. And pray for those who persecute and slander you. Matthew 5:44

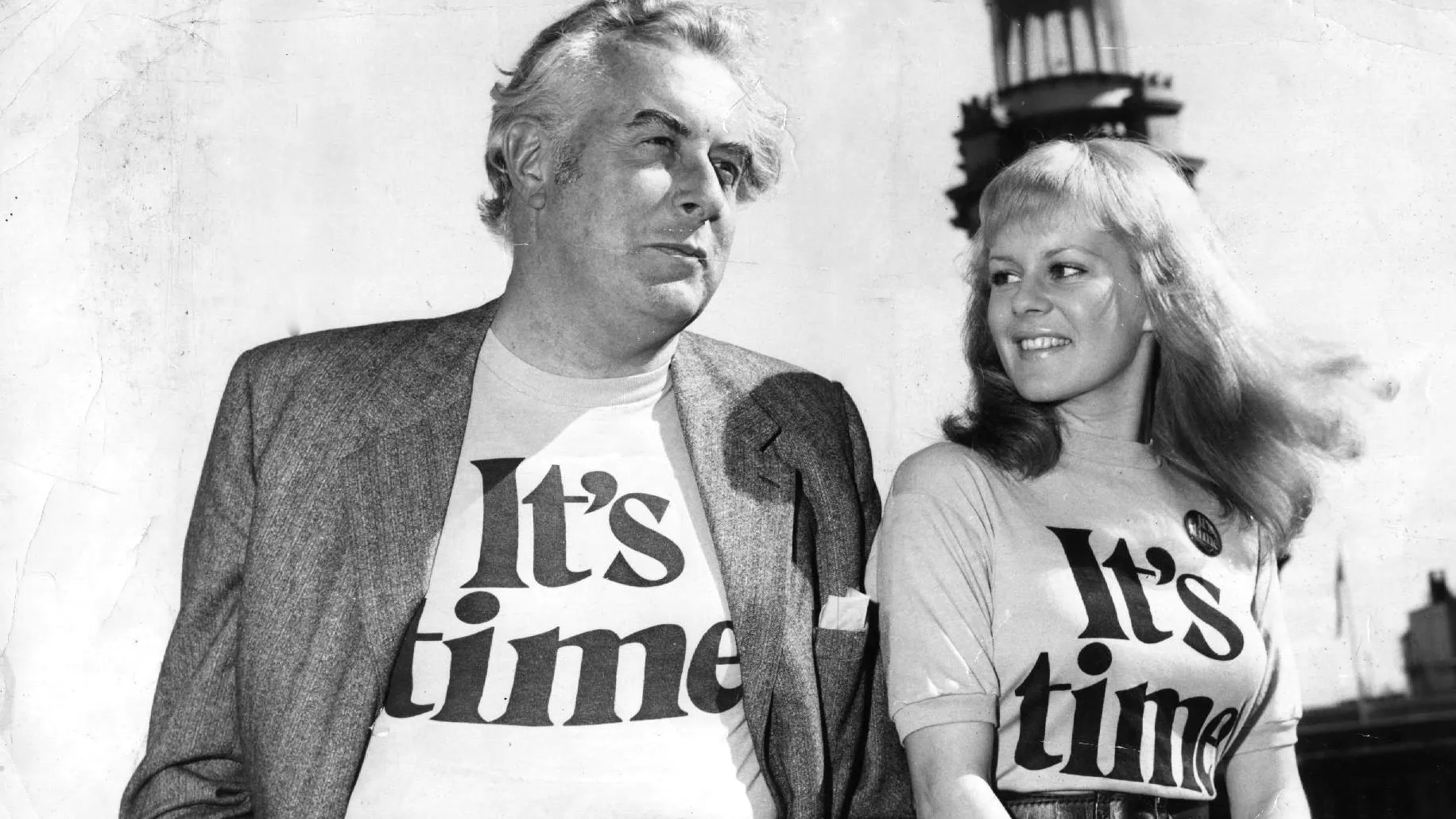

Wearing your politics

In a robust democracy, you can walk down the street wearing the colours and symbols of any candidate or organisation you desire.

The Introduction of Decimal Currency: How We Avoided Nostrils and Learned to Love the Bill

On 14 February 1966, one of the most fundamental aspects of Australians’ lives underwent a radical transition.

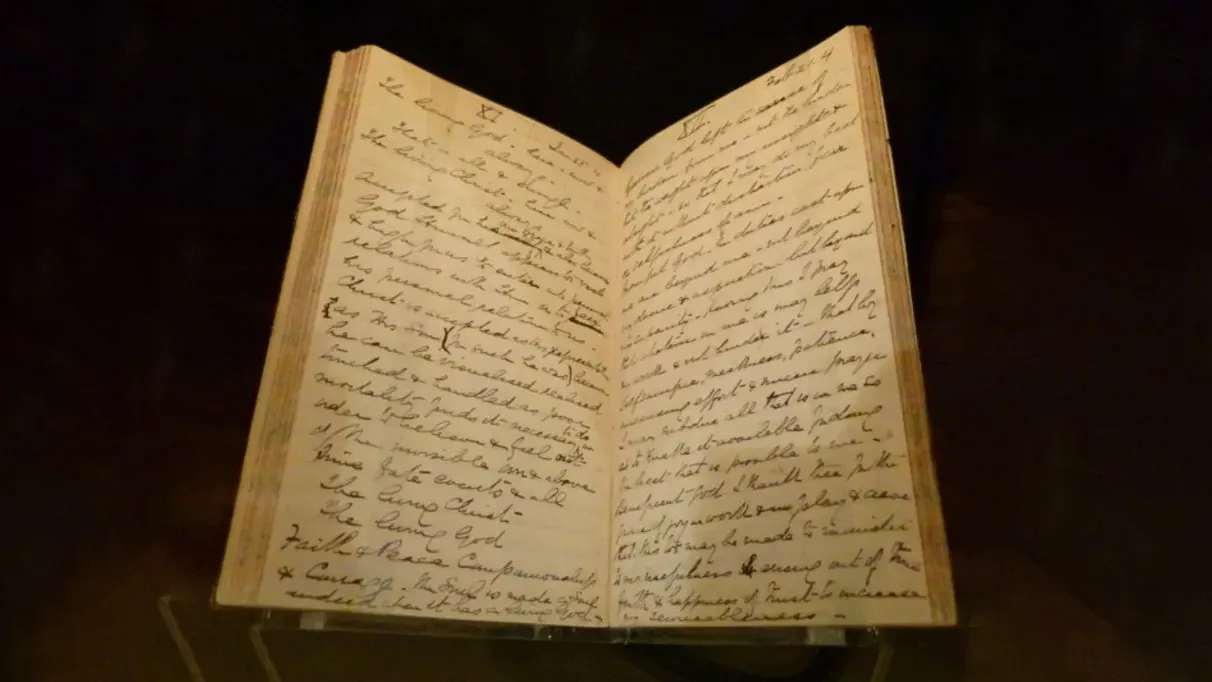

Love letters at the heart of politics

While democracy isn’t usually synonymous with romance, we have a few gems in our collection that get right to the heart of politics…

The Father of the House

In February 2016, the Hon. Philip Ruddock MP, Father of the House, announced his retirement after forty-three years in the federal Parliament.

Prime Minister Harold Holt's 692 days as leader of Australia

On 26 January 1966, Harold Holt became Australia’s 17th prime minister.

The day Robert Menzies retired

Robert Menzies resigned as prime minister in January 1966, ending the longest period – 16 years – as national leader in the history of Australian democracy.

What does one do after leaving the top job?

One characteristic shared by almost all 28 former prime ministers is a marked reluctance to relinquish the office.

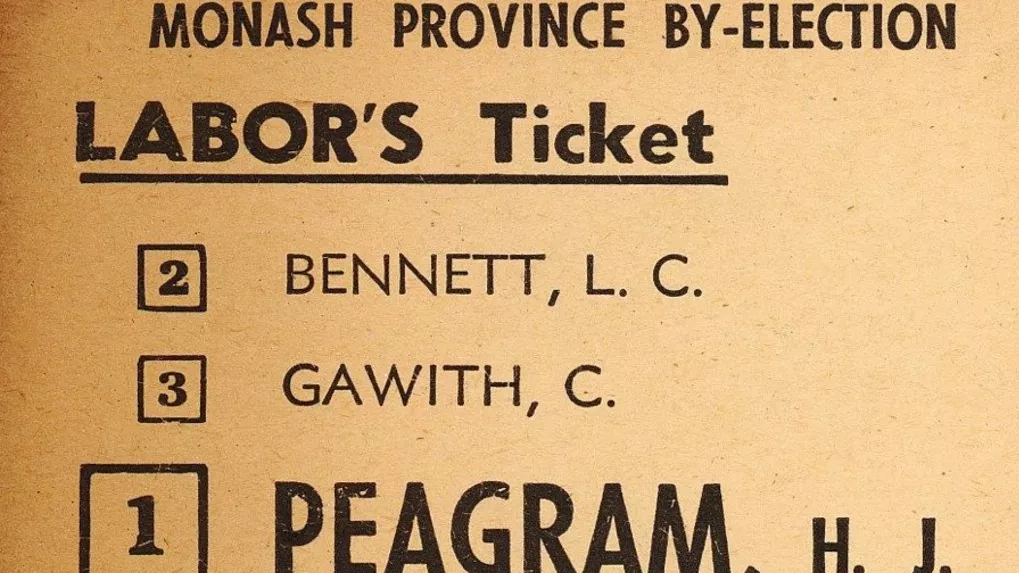

By-elections in Australia

By-elections are called when there is a need to replace a member of the House of Representatives who has resigned or died.

Leadership spills: nothing new to history

Australia had a new prime minister in 2015, and for the third time in five years the transition of power occurred as the result of a leadership spill in the government.

The decriminalisation of homosexuality

On 27 August 1975, South Australia became the first Australian state to fully decriminalise homosexual acts.

Who knew that toilets would have such a complicated history?

The history of the lavatories of Old Parliament House has inspired more scrutiny and newspaper ink than you might think. Especially for the women in the building.

Establishing the United Nations

The 24th of October is commemorated each year as United Nations Day.

Vale Faith Bandler

On Friday 13 February 2015, Faith Bandler AC passed away at the age of 96.

Vale the Hon. Tom Uren AC

With the passing of the Hon. Tom Uren (1921-2015), Australia has a lost a remarkable and dedicated political figure.

Vale Reg Withers

Monday 15 November 2015 saw the death of former Fraser government minister Reginald Greive ‘Reg’ Withers at the age of 90.

A 'follitical' liability?

Even to those unfamiliar with the luminaries of early Australian federal politics, photographs of the era’s protagonists reveal an obvious and unmistakable distinction from later generations of politicians.

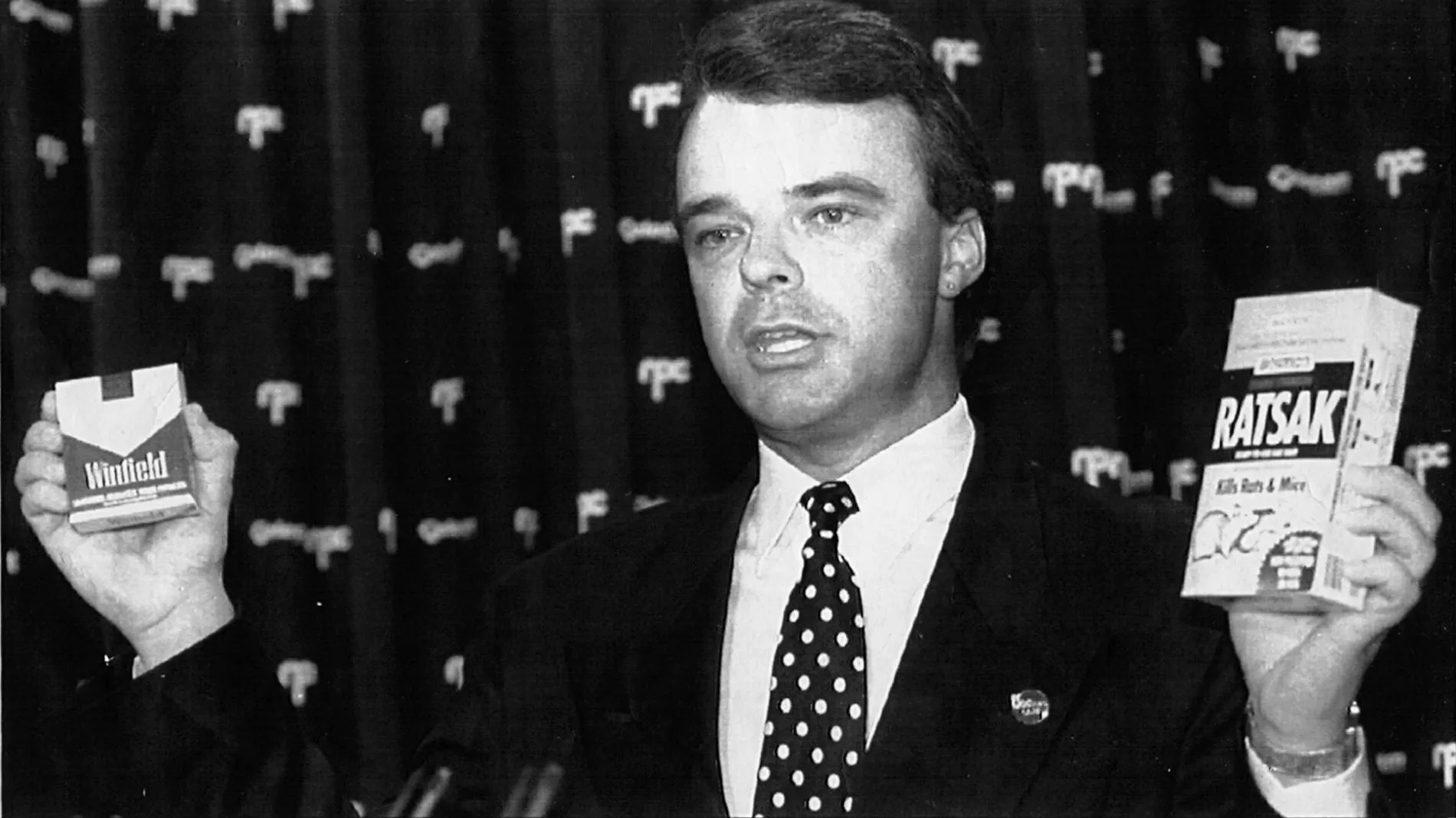

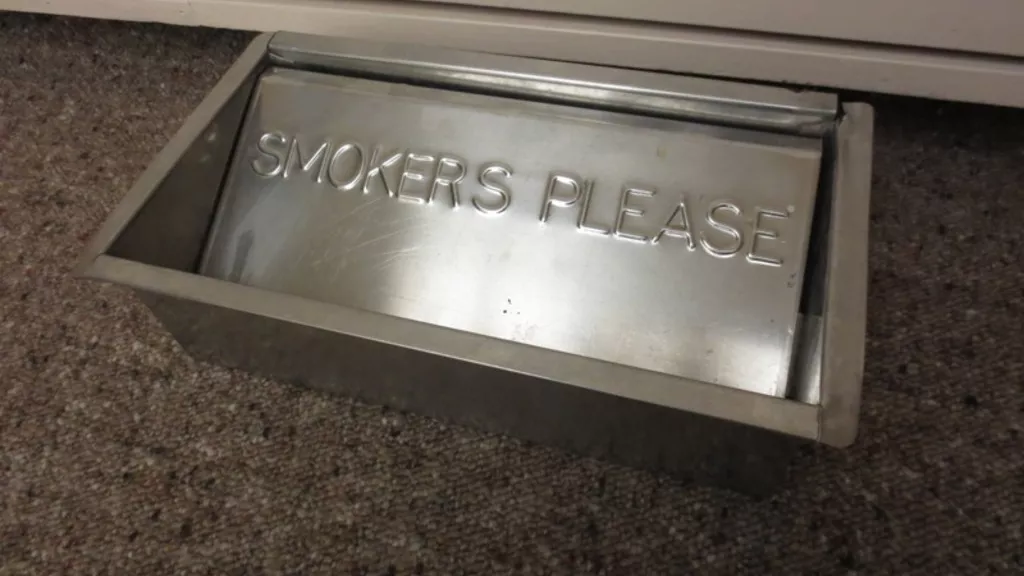

Butting out a ciggie in Old Parliament House

Were you a smoker when Old Parliament House was the federal parliament? If so, then you were in good company as smoking was common.

A perfect picture of the statesman: John Christian Watson

A notable date, 27 April, marks the anniversary of the Watson government.

Anzac Day at the provisional Parliament House

For several years in the late 1920s and 1930s, before the opening of the Australian War Memorial, the provisional Parliament House was the focus of Anzac Day ceremonies in Canberra.

Australia’s entry into the Second World War

As Australia went onto a war footing, the Australian Parliament readied itself for action.